New Delhi, 27th of March 2012

Please find here the link to the original article

If conceptualised carefully, the Bank can help rebalance the global economy leading to equitable and resilient growth.

Even as New Delhi prepares for the arrival of BRICS Heads of States towards the later part of the week, media and experts across the world continue to debate the relevance, capacity and cohesiveness of the grouping. The common refrain in the western press is that it is a ‘motley crew’ with little in common and therefore with little capability to create institutions and multilateral platforms of substance. Well, they may be in for a surprise. In fact, BRICS may also surprise itself.

Besides the usual declarations on cooperation on political matters, social challenges, climate and energy, food and water, health and education, industry and trade, BRICS is likely to make two significant announcements this time, which will, in many ways, mark its coming of age. First — the formal launch of the “BRICS Exchange Alliance” in which the major stock exchanges of BRICS countries will offer investors index-based derivatives trading options of exchanges in domestic currency. This will allow investors within BRICS to invest in each other’s progress, expand the offerings of the individual exchanges, facilitate greater liquidity, while simultaneously strengthening efforts to deepen financial integration through market-determined mechanisms. From talking to people in the know, this alliance is good to go, and the operational modalities around currency, settlement cycles and inter-exchange regulatory coordination are all issues that have been thought through and resolved.

‘South-South bank’

The second announcement that has people most interested is on the much discussed “BRICS Bank” or the “South-South Bank” that many consider to be an Indian proposal for creating an institution that can serve the development needs and aspirations of the emerging and developing world. This proposal saw much debate (some heated) at the recent BRICS Academic Forum and surely was a key issue for deliberations at the recently concluded BRICS Finance Ministers Meeting. There are many complex and some contested issues that need to be discussed and thought through, but due to the growing support for such an institution among BRICS it is almost certain that the leaders will, at the very least, announce a working group to study the feasibility and operational modalities of such a multilateral bank. Whether they are bold enough to suggest a time line for its establishment remains to be seen but in the opinion of many, it is an idea whose time has come.

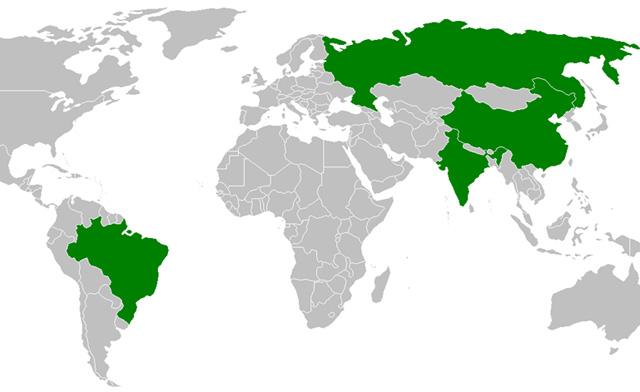

Foremost amongst the reasons for the creation of the institution is the need for BRICS to assume pole position in global financial governance. BRICS nations represent nearly half the world’s population. Two of them are already among the top five economies in purchasing power parity terms, and four are in the top 10. If conceptualised carefully, such an institution will have the potential to reshape and realign the global development agenda positively. It can also help to efficiently redistribute and redirect savings available with the emerging economies to infrastructure and social development in the same regions and, therefore, contribute to the rebalancing of the global economy.

Several multilateral banks already exist, that serve as templates for creating a new institution. The World Bank, which is deeply embedded in the global development narratives, serves as a particularly relevant example. If a multilateral BRICS bank is instituted, its functions would not supplant the role of existing multilateral banks that support development, but rather, supplement them. And this supplementary instrument is needed as multilateral banks such as the World Bank, ADB, etc., have not been growing significantly in terms of the total amount of loans disbursed. While there was a jump in disbursals following the financial crisis, the normalisation process is already under way. On the other hand, demand for funds for infrastructure and social transformation grows unabated in BRICS and the developing world.

But how would the BRICS Bank work? There are doubts expressed in some quarters on the process of capitalisation itself. The Bank would have to raise capital from open market operations; floating debt to finance lending operations. While the reliance on markets for raising capital would make the fiscal asymmetries within BRICS nations irrelevant, the sovereign ratings of some of the members, who will collectively be the shareholders of a BRICS Bank, are barely investment grade. This would limit the amount of capital that could be raised from the financial markets and also affect the cost of capital and therefore the cost of lending. One suggested solution is the sequestration of a proportion of foreign reserves of BRICS members into a trust fund that would back-stop the borrowed capital. In the case of the World Bank, the total paid-up capital is around 10 per cent while the rest is AAA rated ‘callable capital’, which has never been requisitioned. To enhance the creditworthiness further, existing multilateral banks, and other western countries could also be given minority stakes.

China’s role

The second element that is always embedded in the discussions around the bank is the role of China. An impression is sought to be created that with its massive monetary reserves and political clout, China may exert undue influence in this bank. This is unlikely. Such a bank will not require too much paid-up capital (relative to the average size of respective sovereign reserves) if intelligent financial engineering can help sequester foreign reserves. This would mean that the smallest BRICS economy, South Africa, could easily commit an amount similar to that of China in the capital structure. Such doubts could be further allayed with the institution of a rotating Presidency of, say, a two-year term that could initially be restricted to the BRICS countries alone. In any case, the charter of any modern day banking institution with sovereign stakeholders would need to include the mandates of transparency and independence, which would make the institution as viable as any.

The third aspect that remains central to the viability of such a bank is the currency of business. There would be expectations that such a bank would transact in local currencies where possible and in international currency when needed. The bank would need to work with the right currency mix to mitigate credit risk while simultaneously balancing intricate political dynamics within BRICS. For instance, being a current account deficit country, India would not be averse to the U.S. dollar being the currency of disbursal while Brazil with its appreciating “Real’ may prefer local currency. The Chinese may see this bank as a platform for promoting the Renminbi as the currency of choice, especially among the emerging and developing countries. Ultimately, the right mix would need to take into account monetary policy and exchange rate imperatives of each of the primary sovereign stakeholders and in a manner that makes this venture uncomplicated and attractive to other stakeholders as well.

The fourth aspect is the business mandate of such a bank. An effective development bank would have to integrate the multiple economic priorities. Key areas such as infrastructure and the medium and small scale enterprises sector could be natural starting points. The Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) could be considered an exemplar. The BNDES disbursed close to $140 billion in 2011, with around 30 per cent going to the medium to small enterprises sector (MSME) and about 40 per cent going to large infrastructure projects. The BNDES also played a crucial role in stabilising the Brazilian economy after the financial crisis by stepping up development assistance. Similarly, a BRICS Bank could also assume the role of a financial support mechanism which appropriately responds to the variabilities in the global economy.

Corporations are the primary growth drivers of BRICS economies. They create economic momentum, new business opportunities and, most importantly, in the context of BRICS, employment. The creation of SPVs to cater to the investment and insurance needs of corporations would therefore complement the development agenda. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) provide readymade frameworks. The IFC provides investment solutions for the private sector through services such as equity finance and structured finance, while the MIGA provides non commercial risk insurance guarantees. Guarantees against political risk — which is a significant investment constraint in emerging markets — could facilitate a spurt of new business activity within BRICS, and lest we imagine this instrument to be risk-laden, MIGA has paid only six insurance claims since it was set up in 1988 and needs no counter guarantees.

Need for consensus

BRICS is in transition and cannot afford to lose growth momentum. Multilateral institutions such as a BRICS Bank can aid in sustaining directed, equitable and resilient growth. A consensus on the creation of such an institution would be a very real expression of intent by BRICS to craft alternative development trajectories to those passed down by the OECD countries. And it is also time to Bank with BRICS.

Samir Saran is Vice-President and Vivan Sharan an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation. The foundation hosted the BRICS Academic Forum in March this year.