Abstract

More investment is needed to achieve the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement. This Policy Brief suggests that the solution lies in increasing climate FDI—cross-border investment aligned with climate goals—by creating a ‘climate-friendly investment climate’. The authors recommend four targeted measures, drawing from a new ‘Guidebook on Facilitating Climate FDI’, to be published by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with Wavteq/fDi Intelligence: (1) Align investment promotion agency (IPA) strategies, key performance indicators (KPIs), incentives and de-risking instruments to climate goals; (2) Create a database of sustainable suppliers and a supplier development program to help domestic firms become sustainable; (3) Map multinational enterprise climate commitments and create a pipeline of endorsed and vetted carbon-neutral investment projects that help MNEs deliver on their commitments; and (4) Include climate FDI provisions in international investment agreements and national legal frameworks. Finally, a Coalition of IPAs for Climate is proposed to increase knowledge, facilitate cooperation, and drive action to increase climate FDI. The Coalition can use the measures to help facilitate two-way climate FDI between G20 economies, resulting in mutually beneficial outcomes.

1. The Challenge

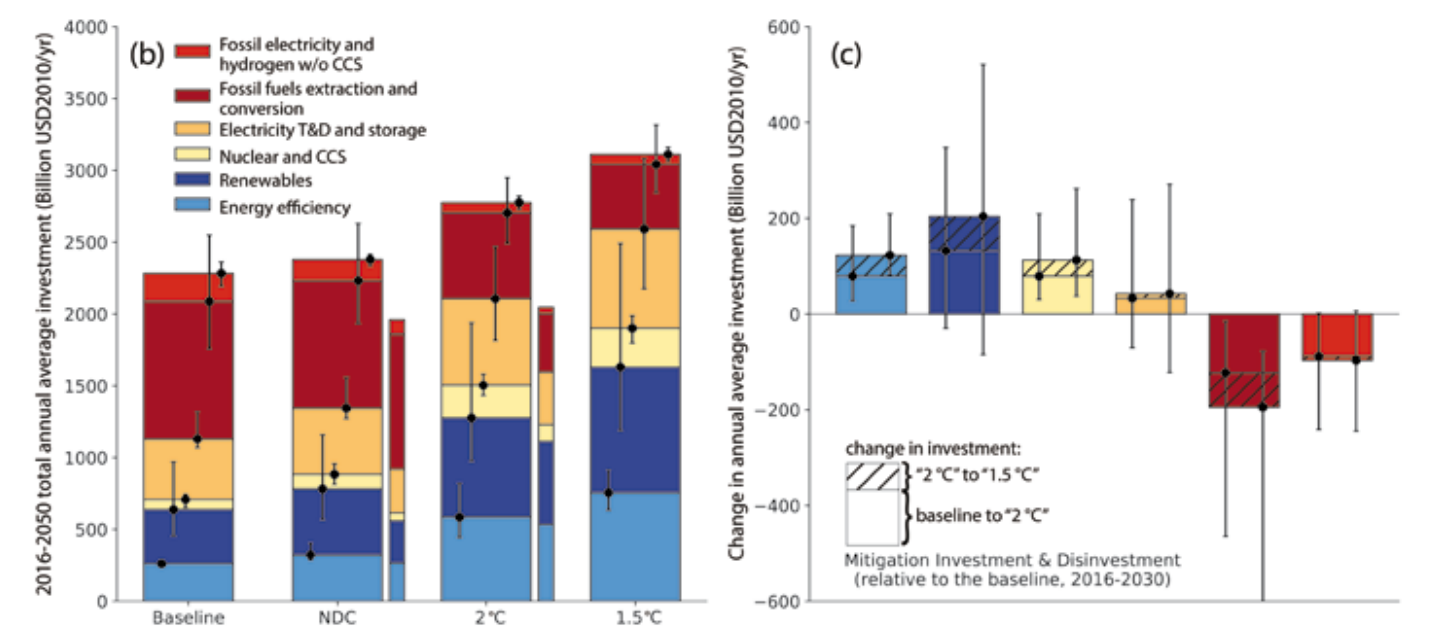

According to IPCC estimates, about US$800 billion in new investment in energy systems is required each year between 2012 and 2050, to reach the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C (de Coninck et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 361). This is in addition to current investment trends. Estimates place the baseline investment in energy systems at US$2.38 trillion of yearly investments, compared to the US$3.2 trillion that is needed (de Coninck et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 321).

Figure 1. Historical and Projected Global Energy Investments in Different Scenarios (2016-2050)

Note: The left figure uses six global models to represent four different scenarios: investment in energy systems that continue along the current baseline (i.e., pathway without new climate policies and measures beyond those already in place), increasing investment to achieve nationally determined contributions (NDCs), increasing investment to keep global warming to 2°C, and increasing investment to keep global warming to 1.5°C. The bars represent the model means, while the whiskers the full model range. The right figure represents the needed change in investment to keep global warming at 2°C or 1.5°C relative to the baseline. Whiskers show the full range around the multi-model means.

Source: Rogelj et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 155

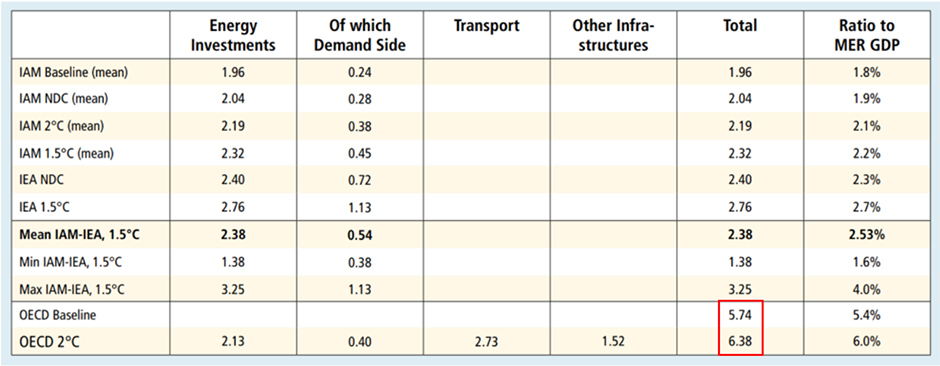

What about beyond energy systems? Earlier OECD estimates place the total investment needed at around US$6 trillion (see Figure 2, red box). These are astoundingly large figures.

Figure 2. Energy Investments Vs Other Investments for Climate Goals (2015–2035)

Note: Estimated annual world mitigation investment needed to limit global warming to 2°C or 1.5°C (2015–2035 in trillions of USD at market exchange rates).

Source: de Coninck et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 373

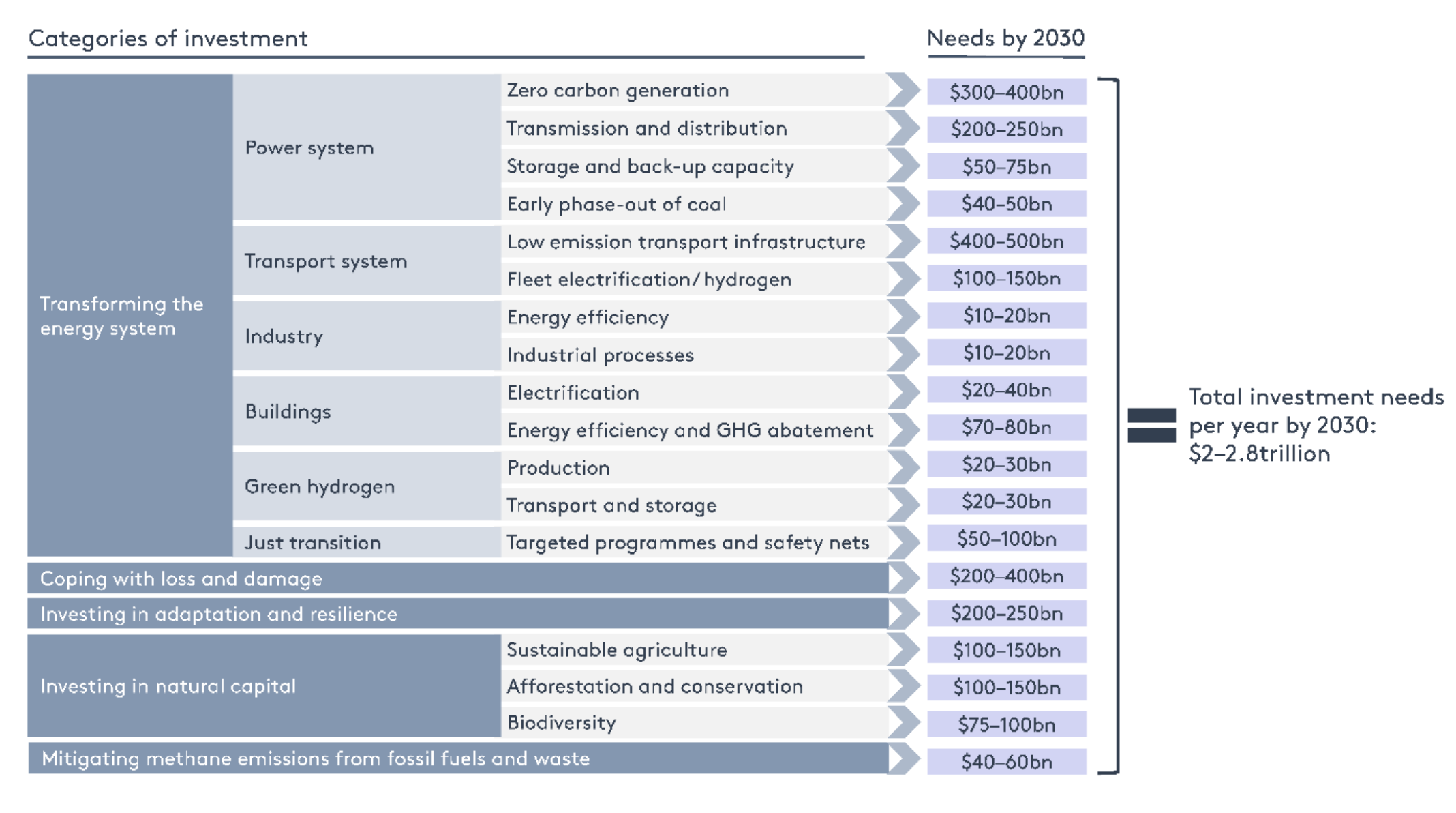

More recent estimates suggest that between US$2 and US$2.8 trillion in investment may be needed every year to reach climate goals (Songwe et al., 2022), as shown in Figure 3. This may not always require new investment but a combination of mobilising new investment and the reallocation of existing capital.

Figure 3. Investment Needs for Climate Action Per Year by 2030

Source: Songwe at al., 2022, p. 23

How will the world mobilise new investment and reallocate existing capital? The capital will need to come from both public and private sources, but much more is needed to unlock and crowd-in private capital in this area.

The challenge is creating the right conditions to grow such investments. In other words, creating a ‘climate-friendly investment climate’.

The solution lies in a combination of institutional capacity and domestic reforms through improved policies and measures (Songwe et al., 2022: 28). Creating a climate-friendly investment climate will need to include policies and measures both on the demand side (encouraging increase in the consumption of low-carbon goods and services) and policies and measures on the supply side (encouraging increase in the production of low-carbon goods and services) (Prest 2022). Policies and measures will also need to address risks associated with scale-up in climate investments, including political, commercial, technological, and currency risks. Policies and measures will also need to promote, attract, facilitate, and incentivise such investments.

The question is what, exactly, policymakers should do.

Two recent analyses attempted to answer this question, including a T20 policy brief in 2022 (Sauvant et al., 2021; Stephenson and Zhan, 2022). The first provided an initial list of potential policies and measures, while the second defined climate FDI[a] and helped build a list of 15 different potential policies and measures.[b]

While this was a commendable start, greater clarity and precision was needed, and the World Economic Forum facilitated a way forward. Across a number of months in 2022 and early 2023, the Forum convened a series of technical meetings with investors, investment authorities, and experts to build on and further refine climate FDI policies and measures.[c] The aim was to produce a ‘Climate FDI Facilitation Guidebook’ that can be used by investment authorities to help grow climate FDI flows.[d] The Guidebook, set to be published in June 2023 in collaboration with Wavteq/fDi Intelligence and made available for free, will provide a ‘how-to’ for four categories of measures identified as particularly important to increasing climate FDI. The four were selected and refined through in-depth consultations (see footnote b), especially considering which measures were most suited to public-private collaboration.

For each of the four priority measures, the Guidebook will lay out: (a) a step-by-step approach; (b) considerations related to implementation and the stakeholders that need to be involved; as well as (c) potential risks and mitigation strategies. The present policy brief aims to capture the primary suggestions to help inform G20 deliberation and action.

2. The G20’s Role

As argued in the 2022 T20 policy brief mentioned earlier, the G20 is the proper forum to support scaling of climate FDI for at least three reasons.

First, climate is one area where G20 economies agree that more action—and especially coordinated action—is needed. The United States (US) and China, for example, notwithstanding their tensions issued in 2021 a number of joint statements and declarations on climate. This indicates that climate action is one area where cooperation is possible even between strategic rivals (State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2021; US Department of State, 2021a and 2021b).

More recently, the US and the European Union (EU) took decisive action to grow climate FDI, whether through the European Green Deal or the US Inflation Reduction Act (2022). The former will encompass €1.8 trillion in investments (European Commission 2023), while the latter includes US$400 billion to help achieve climate goals.

India is also exploring options to attract greater international investment to green sectors, as its remarkable success in expanding green energy has primarily been driven by domestic investments. As of 2020, tracked green finance in India reached US$ 44 billion. Around 83 percent of this was from domestic sources, with the private sector contributing about 59 percent of the domestic investment. However, the annual flows are only one-fourth of the amount needed to achieve the country’s NDCs (CPI, 2022). Thus, it is imperative that international flows must increase rapidly for India to remain on-track to achieve all its NDCs. Within this, FDI will be a priority area for India. Several sectors of the Indian economy are already fairly open to FDI, with minimum regulation; indeed, certain sectors such as renewable energy and electric vehicles have already seen inflows of some form of climate FDI. India will be keen to scale this up, while ensuring that these investments do not come with any conditions that may compromise its ambitious plans to establish a robust manufacturing ecosystem for green industries.

Second, firms carrying out the bulk of FDI are from G20 economies, and therefore helping them grow climate FDI will have a big impact on the world’s climate outcomes (Stephenson and Zhang, 2022, p. 14). Third, once G20 economies adopt policies and measures in support of climate FDI, this will create both a signalling and demonstration effect for non-G20 economies to consider similar approaches.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Recommendation 1. Consider adopting a conceptual framework and definition of ‘climate FDI’ to facilitate coordination and cooperation.

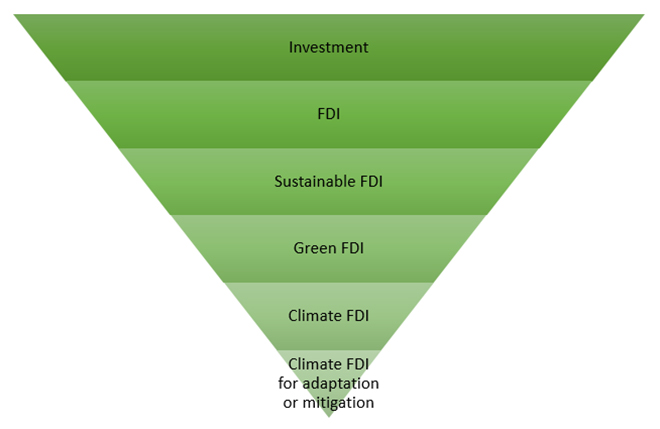

The way to think about climate FDI can be captured in an upside-down triangle that shows the relationship between different types of investment (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Conceptual Framework for Climate FDI

Source: Based on Stephenson and Zhang, 2022: p. 6, updated and revised.

The broadest category includes any investment, whether portfolio investment or direct investment (either foreign or domestic). Then comes foreign direct investment (FDI) as a subset of investment, and then sustainable FDI as a subset of FDI. Sustainable FDI can be defined as FDI that follows principles of responsible business conduct (RBC) and contributes to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals. Continuing down the narrowing conceptual path, green FDI is FDI that aligns with and contributes to the ‘E’ part of ‘ESG’ or the environment. Finally, climate FDI is FDI that aligns with and contributes to the climate dimension of the environment. Within climate FDI, certain projects can contribute to climate adaptation while others, to climate mitigation.

It is worth illustrating the difference between green and climate FDI to avoid confusion. On the one hand, consider an FDI project that ensures that effluents are cleaned before flowing into a river (‘clean river’ example). This would be an example of green FDI, as it does not have a climate impact. On the other hand, consider an FDI project that uses cleaner energy in production that was previously used in that location for that activity (‘clean energy’ case). This would be an example of climate FDI, as it has a climate impact (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Green FDI vs Climate FDI: The Clean River Vs Clean Energy Examples

Recommendation 2. Consider endorsing and using the ‘Climate FDI Facilitation Guidebook’, both within G20 and non-G20 economies through capacity building and technical assistance.

The overall recommendation to the G20 is to consider endorsing and using the Guidebook to grow climate FDI both in their own, and in other economies. G20 policymakers can ensure that their investment authorities consider the Guidebook, especially investment promotion authorities (IPAs). In addition, G20 economies may wish to provide technical assistance and capacity building to authorities in emerging markets and developing countries to consider implementing measures in the Guidebook. This will bring about two interrelated benefits. It will help improve the climate friendliness of investment climates in these economies, and thus help facilitate G20 climate FDI into those economies. At the same time, it will help lower emissions and the carbon content of investment projects around the world, which is needed given the inherently global nature of the climate challenge. Nevertheless, it is important to realise that emerging markets and developing countries may not be in the position to decarbonise as quickly as more developed nations. The solution is to be guided in terms of the depth and direction of climate FDI measures by commitments in each country’s NDCs, as by definition these climate commitments are in line with the priorities and capacities of the country in question.

Finally, different measures will be more relevant to different economies at different points in time. The Guidebook provides four categories of policies and measures to consider, though policymakers may wish to adopt and implement specific measures according to the political and economic conditions in each country.

Measure 1. Align IPA strategies, KPIs, investment incentives and de-risking instruments to NDCs.

The first category of measure is to align IPA strategies, KPIs, investment incentives and de-risking instruments to climate goals identified in NDCs. For instance, ensuring that investment incentives are aligned with—and thus help deliver—NDC goals. Incentives should include not just the fiscal[e] and financial but also those of a non-monetary nature.

Examples of non-monetary incentives can be captured by the heuristic of a ‘red-green-gold’ approach: speed of approvals (red carpet treatment), expedited customs clearances (green channel process), and targeted aftercare (gold status treatment). De-risking instruments such as purchase guarantees (e.g., renewable power purchase agreements) and investment insurance are also important to help crowd-in climate FDI. It is worth noting that insurance many need to address different types of risk, e.g., political risk, commercial, currency risk, and the risk of technology changing and making some technological choices obsolete before the end of the project’s lifetime.

Figure 6. Steps to Roll Out Measure 1

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Measure 2. ‘Match and catch’

The second category of measures is to create a database of domestic suppliers with sustainability dimensions, along with a supplier development program to help domestic firms become more sustainable. This helps ‘match’ investors to domestic suppliers and helps domestic firms ‘catch up’ to the level required by investors.

Having a database of domestic suppliers facilitates investment because it helps overcome information asymmetry between foreign and domestic firms, providing foreign investors with information on domestic suppliers of goods and services they can source domestically. This will lower the time and cost for foreign firms to operate, since they can source inputs domestically that they would otherwise have had to produce themselves or else import.

Supplier databases can be designed to include not only traditional information such as the goods and services offered and contact information, but also information on how domestic firms are operating sustainably. This can help foreign firms select and negotiate contracts with domestic firms that are operating in a climate-friendly manner. It will also encourage domestic firms to increasingly shift to a climate-friendly way of doing business in order to attract and qualify for foreign capital that either aims or requires to be contracting with firms that are operating in such a manner. This has been called a ‘virtuous sustainable investment cycle’ (Stephenson, 2020).

At the same time, supplier development programs can help with the technical assistance and capacity building needed for domestic firms to provide goods and services at the quality, cost, and scale required by foreign firms. Supplier development programs can also be oriented to helping domestic firms acquire the certifications and reach standards of sustainable operations, which can be reflected in the supplier database. When information regarding sustainable operations is included in a supplier database, the database is known as a ‘supplier database with sustainability dimensions’ (SD2). The first SD2 was created by the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC), with the support of the World Economic Forum (CDC, 2023). Other economies may wish to ensure that their supplier databases also include sustainability dimensions.

Figure 7. Steps to Roll Out Measure 2

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Measure 3. Help them help you

The third category of measures is to map the climate commitments of multinational enterprises (MNE) to investment opportunities in host economies and create a pipeline of endorsed and vetted carbon-neutral climate-friendly investment projects that would help MNEs deliver on their commitments. Endorsement by the host government of the pipeline of investment projects de-risks investment in countries that may have relatively more risk or unpredictability.

At the same time, vetting by a third party provides validation and verification that the investment would be designed and implemented in a climate-friendly manner. This creates more certainty for investors to carry out climate investment, as the evidence shows that certainty and predictability are of utmost importance for investment decision-making.

Figure 8. Steps to Roll Out Measure 3

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

How can investment authorities determine MNE climate commitments? Table 1 provides a snapshot of the different platforms where this information may be available. This can help kick-start the search for a good fit between these public commitments and the climate FDI projects that an economy can propose.

Table 1. Potential Sources to Identify MNE Climate Commitments

| Platforms | Description | Strengths & Weaknesses | Examples |

| 1. Company websites & social media | • MNEs may publish their climate commitments, corporate sustainability reports and progress reports on their own websites.• This allows MNEs to showcase sustainability efforts and report on progress made in achieving targets to a wider audience.• Platforms like LinkedIn and Twitter can be used to publish progress reports and engage in conversations with stakeholders. | • Direct engagement with stakeholders and key interest groups.• MNE is accountable to the wider public if climate commitments/pledges are published online.• MNE controls messaging on their websites.• No requirement for commitments to be specific, or mandatory progress reporting to be published on websites. | • Nestlé published commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, using 100% renewables in its operation by 2025[f]• American Airlines published their ESG Report which states their action plan of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2020[g] |

| 2. Sustainability and reporting platforms/ rankings | • Several third-party platforms publish and report on MNE climate commitments to manage their environmental impacts.• In most cases, this information is self-reported and in some cases, independently verified.• Key metrics that are collected and reported on include: GHG emissions, renewable. electricity usage, supply chain emissions, carbon reduction targets and progress made in achieving them. | • Publishing commitments on a recognised third-party platform can increase the credibility of a company’s climate commitments.• Publishing commitments on a third-party platform may garner the MNE greater visibility (beyond their own website/social media).• Several reporting platforms and rankings offer benchmarking services that will allow MNEs to compare their commitments and performance against peers or the industry standard.• Participating in a third-party platform may not always be free (e.g. fee for participation, data collection, consultation). | • SBTi[h]• CDP[i]• Ecovadis[j]• Sustainability Accounting Standards Board[k]• The Climate Pledge (initiative supported by Amazon and Global Optimism) has been joined by more than 300 businesses across 51 industries and 29 countries[l] |

| 3.Industry-specific initiatives | • Some industry have their own sustainability initiatives and platforms for industry players to publish their climate commitments/pledges. | • Allows comparison and comparability of MNE commitments across the industry, and can promote collaboration as companies share best practices in achieving climate commitments.• May promote a one-size-fits-all approach to climate commitments, which may not be meaningful depending on industry composition. | • First Mover Coalition[m] |

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Measure 4. The 5 Cs of climate in IIAs: Clarification, Coordination, Competence, Compel, Carve out

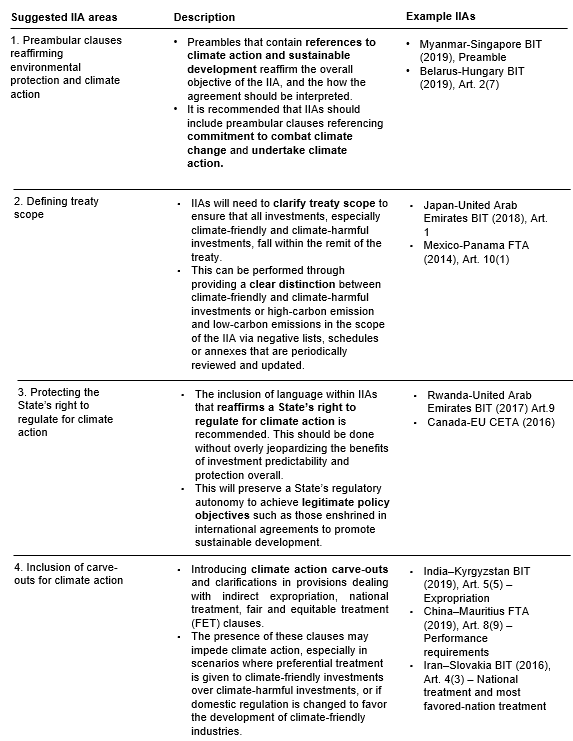

The fourth category of measures is to include climate FDI provisions in international investment agreements (IIAs), with the aim of complementing approaches outlined above with legal instruments.

Under efforts of both UNCTAD (2022a, 2022b) and OECD (2022), a new generation of IIAs is being developed, reforming earlier IIAs and helping develop instruments that accurately reflect society’s climate goals. Concretely, there are a number of ways that climate FDI goals can be integrated in clauses and provisions within a new generation of IIAs (see Table 2).

These can be captured by the five Cs of climate in IIAs:

- Clarification clauses/provisions on how the treaty relates to and covers climate goals

- Coordination provisions that encourage the facilitation of climate FDI between parties

- Competence provisions that convey the state’s right to regulate for climate goals

- Compel provisions that require the parties and their firms to adhere to standards or actions

- Carve out provisions that do not provide the same protection to climate negative investments

Table 2. Ways to Include Climate FDI Provisions in IIAs and Examples

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming), based on UNCTAD (2022a and 2022b) and OECD (2022)

When reviewing and reforming IIAs or developing new IIAs, it is important to ensure that the text aligns with sustainable objectives and climate objectives, while also promoting, facilitating and protecting investments. One suggested aspect to consider is the inclusion of clauses that encourage and facilitate climate FDI (or sustainable investment more broadly), as prima facie this would only have upsides and no downsides, in that such provisions are likely to only help support and promote climate FDI flows. This approach is captured above by the second ‘C’, ‘2. Coordination’.

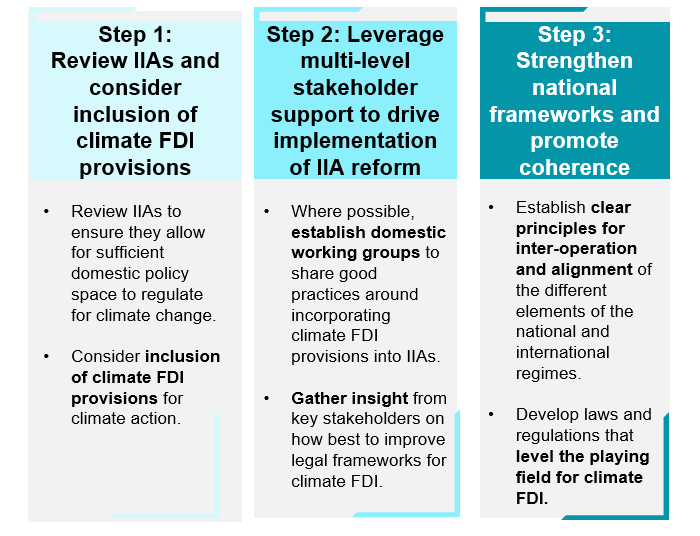

It is worth acknowledging that approaching climate FDI from the legal side will take longer than any of the earlier measures that are easier to facilitate. However, notwithstanding the greater time and effort this may take, over time, climate FDI provisions in legal instruments are likely to have a significant impact on growing these investments. Figure 9 suggests how investment authorities may approach this process.

Figure 9. Steps to Roll Out Measure 4

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Recommendation 3. Consider creating a Coalition of IPAs for Climate.

One way to help operationalise climate FDI measures and scale collaboration on growing such investment is through a potential Coalition of IPAs for Climate.[n] This idea is currently under discussion, with the aim of potentially launching such a coalition in Davos in January 2024. The World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (WAIPA), which supports the initiative, will play in important role.

What would the coalition do in practical terms? As a first step, coalition members would first endorse at the CEO level a statement—circulated and discussed in Davos in January 2023 (see Annex)— on the importance of increasing climate FDI and the opportunity to use climate FDI measures to do so. As a second step, coalition members would aim to use the Guidebook to implement climate FDI measures.

While there have been a number of other coalition mechanisms to mobilise action in support of climate goals, this would be the first time that IPAs specifically add their voice and muscle to the effort. To illustrate, the First Movers Coalition brings together 65 companies and at least 10 government partners so far, that have committed to support carbon goals through procurement decisions (US Department of State, 2022). Meanwhile, the Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate brings together ministers from 50 countries that have agreed to leverage trade for climate goals (EC, 2023). Adding the investment piece to this puzzle could help all parties better achieve climate goals, given that investment and trade are two sides of the same coin, and that procurement can be considered a form of investment.

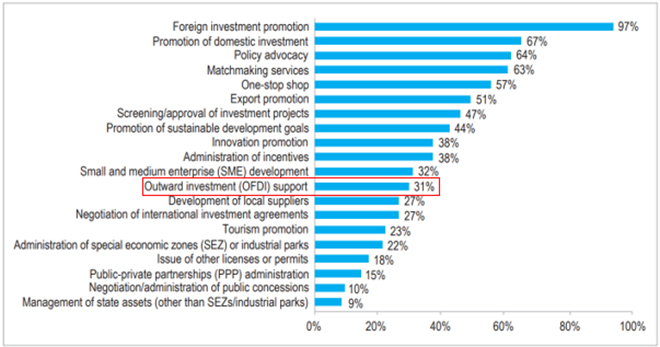

In addition, FDI flows are increasingly two-way, with IPAs facilitating not only inward FDI, but also outward FDI (see Figure 10, red box). This is due to the realisation that outward FDI can lead to increased growth and competitiveness of firms and home economies, acting as complementary channel to inward FDI for development (Stephenson and Perea, 2018). As a result, there is scope for two-way, mutually beneficial climate FDI facilitation between IPAs of G20 economies, as one economy’s inward FDI is by definition another economy’s outward FDI (Stephenson, 2018).

Figure 10. Incidents of Mandates of IPAs (2019, n = 91).

Source: Sanchiz Vicente and Omic (2020)

4. Conclusion

The world needs more investment to help achieve and deliver its climate goals—but where to start? This policy brief outlined four concrete, practical measures that G20 policymakers may wish to consider, providing step-by-step suggestions for how to do so. These measures are captured—and further developed—in a Guidebook on Climate FDI Facilitation, which provides more detail on each, and can serve as a complementary resource. A Coalition of IPAs for Climate could also help catalyse and scale cooperation in this space, providing mutually gainful outcomes for G20 economies, and the world.

Attribution: Matthew Stephenson and Samir Saran, “Creating a Climate-Friendly Investment Climate,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Annex

References

de Coninck, H., A. Revi, M. Babiker, P. Bertoldi, M. Buckeridge, A. Cartwright, W. Dong, J. Ford, S. Fuss, J.-C. Hourcade, D. Ley, R. Mechler, P. Newman, A. Revokatova, S. Schultz, L. Steg, and T. Sugiyama, 2018: Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte,V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M.Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 313-444.

Climate Policy Initiative, Landscape of Green Finance in India, 2022.

Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC), The Suppliers Database with Sustainability Dimensions (SD2), (retrieved 8 April 2023)

European Commission (ECa), “A European Green Deal Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent”, Accessed 8 April 2023.

ECb, Trade and Climate: EU and partner countries launch the ‘Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate, Press Release, 19 January 2023.

International Finance Corporation (IFC), “Climate Investment Opportunities in South Asia: India”, n.d.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Survey of climate policies for investment treaties”, 11 October 2022.

Prest, Brian C. 2022, Partners, Not Rivals: The Power of Parallel Supply-Side and Demand-Side Climate Policy, Resources for the Future, Report 22-06, April 2022.

Rogelj, J., D. Shindell, K. Jiang, S. Fifita, P. Forster, V. Ginzburg, C. Handa, H. Kheshgi, S. Kobayashi, E. Kriegler, L. Mundaca, R. Séférian, and M.V.Vilariño, 2018: Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 93-174.

Sanchiz Vicente, Alex and Omic, Ahmed. State of Investment Promotion Agencies: Evidence from WAIPA-WBG’s Joint Global Survey (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2020.

Sauvant, Karl P. and Stephenson, Matthew and Kagan, Yardenne, Green FDI: Encouraging Carbon-Neutral Investment (October 18, 2021). Columbia FDI Perspectives, No. 316, 2021, SSRN.

Songwe V, Stern N, Bhattacharya A. Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2022.

Stephenson, Matthew. “Investment as a two-way street: how China used inward and outward investment policy for structural transformation, and how this paradigm can be useful for other emerging economies”, PhD Dissertation, Graduate Institute for International and Development Studies, 2018.

Stephenson, Matthew. 5 ways the WTO can make investment easier and boost sustainable development. World Economic Forum Agenda Article, 10 November 2020.

Stephenson, Matthew and Jose Ramon Perea. “Outward foreign direct investment: A new channel for development”, World Bank, Private Sector Development Blog, 23 October 2018.

Stephenson, Matthew and Zhan, James X. What is Climate FDI? How can we help grow it? T20 Policy Brief, 2022.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China, US issue joint declaration on enhancing climate action”, 11 November 2021, Xinhua.

US Department of State, “U.S.-China Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis”, Media Note, 17 April 2021, 2021a.

US Department of State, “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s”, Media Note, 10 November 2021, 2021b.

US Department of State, “First Movers Coalition Announces Expansion”, Media Note, 9 November 2022.

[a] “Climate FDI can be determined on the basis of investment impact, rather than the traditional methodology of defining FDI based on investor motivation (Dunning, 1982). In other words, climate FDI is any investment that leads to measurable improvement in climate conditions in a host economy, regardless of sector or activity” (Stephenson and Zhang, 2022: 6).

[b] Related work by Joachim Monkelbaan and Jose Vieira Martins had identified a longer universe of 38 different policies and measures, which was synthesised and prioritised through an internal working group at the World Economic Forum.

[c] Virtual and in-person meetings of the community to discuss climate FDI policies and measures took place on 21 July 2022, 9 November 2022 at COP27, 14 December 2022, 18 January 2023 at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, and on 29 March 2023.

[d] To help produce the Guidebook, specialized consulting firm WAVTEQ was selected as a partner, and has helped build out information on the top climate FDI measures through additional interviews and research. WAVTEQ has since been acquired by The Financial Times.

[e] Fiscal incentives to attract FDI will lose some of their effectiveness following the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process. If host states levy less than the 15 percent minimum tax on firm profits, other specified jurisdictions can charge a ‘top-up’ tax and pocket this amount, incentivising host states to meet the 15 percent threshold or lose fiscal revenue without gaining investment attractiveness. Please see Stephenson and Zhan, “We’ve entered a new era for investment policy and promotion”, forthcoming. The authors also wish to acknowledge Karl Sauvant for raising this point during the 29 March 2023 consultation.

[f] Climate action | Nestlé Global (nestle.com)

[g] American Airlines ESG – American Airlines (aa.com)

[h] How it works – Science Based Targets

[l] The Climate Pledge | Be the planet’s turning point

[m] About > First Movers Coalition | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

[n] This idea was first proposed by Soumyajit (‘Jeet’) Kar, Specialist, Sustainable Trade and Resource Circularity, World Economic Forum.

SOURCE – T20 ORF Policy Brief.