Original link is here

Monthly Archives: July 2017

Trump’s stand on the Paris deal may help India

Trump’s belligerence towards the Paris accords may ironically become its undoing.

Original link is here

The Prime Minister Narendra Modi-President Donald Trump summit offers an opportunity to place in context President Donald Trump’s outburst against India earlier this month, as he announced the decision of the US to step away from the Paris climate agreement. If Trump then alleged that India was making its climate pledges conditional on international funding, the India-US joint statement this week strikes a more sobering note, calling for a “rational approach that balances environment and.. energy security needs.”

Both leaders may have succeeded in moving past this moment of bilateral friction but the Paris proposal from the developed world to India was, and remains, simple and stark. First, India would have to create a development pathway that lifts its millions out of poverty, without the freedom to consume fossil fuels. Second, it would have to discover this new pathway by itself. And, finally, despite its self-financed attempt at balancing poverty eradication and climate responsibility, India would be monitored every inch of the way.

In the past India has been accused of being an intransigent climate negotiator. Under Modi, however, India decided to change its climate narrative. Modi positioned India as a country willing to lead in creating a green model that could then be exported to the rest of the world. It helped, of course, that India had already begun its transformation. Eight months before the Paris Agreement, India had installed 77 GW of renewable energy capacity. By 2022, India aims to expand its renewable energy capacity to 175 GW and will soon have built up the equivalent of German renewable energy capacity, despite having a size of economy a third smaller than Germany.

This transformation underway in India is accompanied by attitudes and decisions in the EU and the US that border on an imperialistic approach to monopolise all available carbon space.

In the past India has been accused of being an intransigent climate negotiator. Under PM Narendra Modi, however, India decided to change it’s climate narrative.

With a distinctly condescending tone, developing nations are told by their richer counterparts that demands for “sustainability” are premised on ethics and morality, discovered belatedly by the developed countries, after colonisation and exploitation of nations, communities and, indeed, of the carbon space. And as with acts of colonial egregiousness, reparations for carbon colonisation are unavailable.

President Trump’s outbursts, though disappointing, were part of a continuum of narratives emanating from the West in the recent past. The attacks against China, India and other developing countries prior to the Copenhagen meet in 2009 and their subsequent vilification sowed the seeds of “climate orientalism”, something that legitimised the current action of the US. In the last seven years, the OECD has added 58 GW of the ‘dirtiest’ form of energy. Germany still burns three times more coal per capita than India. And as of 2016, when measured against the US, India still obtained a higher percentage of its energy from renewable sources. And yet, the hypocrisy of the West has not stopped at the water’s edge of fossil fuel usage.

A small group of developed countries have taken control over the regulatory frameworks and financial flows of the world. The competitive prudentialism of the Basel norms has led to the prioritisation of capital adequacy over credit enhancement. The continued squeezing of sectoral limits driven by the ‘Old Boys’ Club’ in Basel has led to further roadblocks for the developing world to access capital. The risk assessment through black box techniques has meant that the capital that reaches the developing world is priced significantly higher. There is no denying that carbon imperialism exists.

But Trump’s belligerence towards the Paris accords may ironically become its undoing: By highlighting coal and gas, the US president has turned attention on the need for traditional sources. The India-US joint statement cleverly takes advantage of this political impulse and suggests that US energy exports (including coal and gas) should be available to fuel India’s economic development. If ever there was a window of opportunity to dismantle Western shackles on growth and development avenues for the developing world, Trump’s statement personifies it.

This commentary originally appeared in The Hindustan Times.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s).

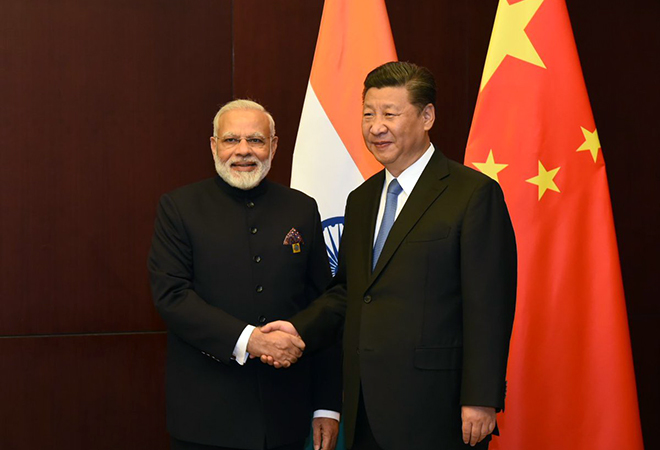

In Armed Conflict With India, Why China Would Be Bigger Loser

Original link is here

The ongoing standoff at Doklam Plateau is less a boundary incident involving India, China and Bhutan and more a coming together of geopolitical faultlines in Asia that were long set on a collision course. China’s wanton aggression, and India’s refusal to be intimidated by it, stem from the different realities they live in. China believes it is destined to lead Asia, and indeed the world, by a process in which other actors are but bit players. India is strongly convinced of its destiny as a great power and an indispensable player in any conversation to re-engineer global regimes.

It is against the backdrop of these competing ambitions that China’s provocations on the Doklam Plateau must be viewed. As the race to establish an Asian order – or at least determine who gets to define it – intensifies, China will test Indian resolve and portray it as an unreliable partner to smaller neighbours. The current differential in capabilities allows China to provoke and understand the limits of India’s political appetite for confrontation, and create a pattern of escalation and de-escalation that would have consequences for New Delhi’s reputation. Its border transgressions are aimed at changing facts on the ground, and allowing for new terms of settlement. For China to engage in a game of chicken, however, would be counterproductive.

In case of an armed conflict, the bigger loser will be China. The very basis of its “Peaceful Rise” would be questioned and an aspiring world power would be recast as a neighbourhood bully, bogged down for the medium term in petty, regional quarrels with smaller countries. For India, a stalemate with a larger nuclear power will do it no harm and will change the terms of engagement with China dramatically.

Through the Doklam standoff, China has conveyed three messages. The first is that China seeks to utilize its economic and political clout to emerge as the sole continental power and only arbiter of peace in the region. Multipolarity is good for the world, not for Asia. When India refused to pay tribute in the court of Emperor Xi Jinping, through debt, bondage and political servility that the Belt and Road Initiative sought from all in China’s periphery, it invited the wrath of the middle kingdom. Confrontation was but a matter of time.

The second message from Beijing is that short-term stability in Asia does not matter to China, because it does not eye Asian markets for its growth. Through road and rail infrastructure along the Eurasian landmass and sea routes across the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, China hopes to gain access to an eighteen trillion dollar European market. Given this reality, no Asian country can create incentives for China to alter its behavior simply with the promise of greater economic integration.

And finally, Beijing has signalled that Pax Sinica is not just an economic configuration, but also a military and political undertaking. Its aggressive posture in the South China Sea, disregard for Indian sovereignty in Jammu and Kashmir, divide and rule policy in the ASEAN region, and strategic investments in overseas ports such as Gwadar and Djibouti are all indicative of its intention to establish a Sino-centric economic and security architecture, through force if necessary. The election of Donald Trump in the United States and political divisions in Europe has only emboldened China’s belief that the reigns of global power are theirs to grab.

Given these stark messages from the eastern front, what can New Delhi do?

The options are limited. The first is to acquiesce to Chinese hegemony over Asia. In the past, India’s foreign policy has attempted to co-opt China into a larger Asian project, from Nehru’s insistence on China’s position on the United Nations Security Council to facilitating its entry into the World Trade Organisation. It is clear today that it was the wrong approach and continuing to play second fiddle to the Chinese will not only involve political concessions but also territorial ones to China-backed adversaries like Pakistan.

The second option for India is to set credible red lines for China by escalating the cost for its aggressive maneuvers around India’s periphery and to increase the cost of “land acquisition” for the Chinese.

Pakistan’s approach vis-à-vis India may prove to be enlightening in this respect. Its development of Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNW) to offset India’s superior conventional abilities and a wide range of asymmetric warfare techniques have ensured that India is disproportionately engaged in regional affairs. For long, the Indian commentariat and diplomatic corps have believed the boundary dispute with China should be suppressed because the bilateral relationship is worth more than just territorial skirmishes. In doing so, they have normalised Beijing’s behaviour, which now allows it to turn the tables and make unsettled boundaries a ceaseless source of tension for India. It is time, therefore, to elevate the boundary dispute as a matter of primary strategic concern and to articulate options to counter Beijing’s threats on the eastern flank. It has done the former by staying away from a project that paid little heed to its sovereignty and territorial concerns. It is time to muster steel and to put together a blueprint for the latter.

China is attempting, vainly, to draw India into a conflict that it believes will prematurely invest it with the label of “first among equals” in Asia. Ironically, Beijing has failed to acknowledge that India does not have to behave like a 10 trillion dollar economy when it is not one – skirmishes, like the one at Doklam Plateau, can be swiftly and aggressively countered by India with little or no loss to its reputation. After all, it would be defending its sovereignty, and in the process, goading China’s smaller neighbours into a similar path. If China wants to be relegated to a disputed regional power, it has only to needle India into a new season of skirmishes and into exacerbating – politically, militarily and diplomatically – Beijing’s multiple land and maritime disputes in Asia.

(Samir Saran is Vice President at the Observer Research Foundation, India.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Why the dragon would be a bigger loser in a clash with the elephant

Samir Saran

The standoff at Doklam is less a boundary incident involving India, China and Bhutan, and more a coming together of geopolitical fault lines.

The ongoing standoff at Doklam Plateau is less a boundary incident involving India, China and Bhutan and more a coming together of geopolitical faultlines in Asia that were long set on a collision course. China’s wanton aggression, and India’s refusal to be intimidated by it, stem from the different realities they live in. China believes it is destined to lead Asia, and indeed the world, by a process in which other actors are but bit players. India is strongly convinced of its destiny as a great power and an indispensable player in any conversation to re-engineer global regimes.

It is against the backdrop of these competing ambitions that China’s provocations on the Doklam Plateau must be viewed. As the race to establish an Asian order — or at least determine who gets to define it — intensifies, China will test Indian resolve and portray it as an unreliable partner to smaller neighbours. The current differential in capabilities allows China to provoke and understand the limits of India’s political appetite for confrontation, and create a pattern of escalation and de-escalation that would have consequences for New Delhi’s reputation. Its border transgressions are aimed at changing facts on the ground, and allowing for new terms of settlement. For China to engage in a game of chicken, however, would be counterproductive.

The current differential in capabilities allows China to provoke and understand the limits of India’s political appetite for confrontation, and create a pattern of escalation and de-escalation that would have consequences for New Delhi’s reputation.

In case of an armed conflict, the bigger loser will be China. The very basis of its “Peaceful Rise” would be questioned and an aspiring world power would be recast as a neighbourhood bully, bogged down for the medium term in petty, regional quarrels with smaller countries. For India, a stalemate with a larger nuclear power will do it no harm and will change the terms of engagement with China dramatically.

Through the Doklam standoff, China has conveyed three messages. The first is that China seeks to utilise its economic and political clout to emerge as the sole continental power and only arbiter of peace in the region. Multipolarity is good for the world, not for Asia. When India refused to pay tribute in the court of Emperor Xi Jinping, through debt, bondage and political servility that the Belt and Road Initiative sought from all in China’s periphery, it invited the wrath of the middle kingdom. Confrontation was but a matter of time.

The second message from Beijing is that short-term stability in Asia does not matter to China, because it does not eye Asian markets for its growth. Through road and rail infrastructure along the Eurasian landmass and sea routes across the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, China hopes to gain access to an eighteen trillion dollar European market. Given this reality, no Asian country can create incentives for China to alter its behavior simply with the promise of greater economic integration.

Short-term stability in Asia does not matter to China, because it does not eye Asian markets for its growth.

And finally, Beijing has signalled that Pax Sinica is not just an economic configuration, but also a military and political undertaking. Its aggressive posture in the South China Sea, disregard for Indian sovereignty in Jammu and Kashmir, divide and rule policy in the ASEAN region, and strategic investments in overseas ports such as Gwadar and Djibouti are all indicative of its intention to establish a Sino-centric economic and security architecture, through force if necessary. The election of Donald Trump in the United States and political divisions in Europe has only emboldened China’s belief that the reigns of global power are theirs to grab.

Given these stark messages from the eastern front, what can New Delhi do?

The options are limited. The first is to acquiesce to Chinese hegemony over Asia. In the past, India’s foreign policy has attempted to co-opt China into a larger Asian project, from Nehru’s insistence on China’s position on the United Nations Security Council to facilitating its entry into the World Trade Organisation. It is clear today that it was the wrong approach and continuing to play second fiddle to the Chinese will not only involve political concessions but also territorial ones to China-backed adversaries like Pakistan.

The second option for India is to set credible red lines for China by escalating the cost for its aggressive maneuvers around India’s periphery and to increase the cost of “land acquisition” for the Chinese.

Pakistan’s approach vis-à-vis India may prove to be enlightening in this respect. Its development of Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNW) to offset India’s superior conventional abilities and a wide range of asymmetric warfare techniques have ensured that India is disproportionately engaged in regional affairs. For long, the Indian commentariat and diplomatic corps have believed the boundary dispute with China should be suppressed because the bilateral relationship is worth more than just territorial skirmishes. In doing so, they have normalised Beijing’s behaviour, which now allows it to turn the tables and make unsettled boundaries a ceaseless source of tension for India. It is time, therefore, to elevate the boundary dispute as a matter of primary strategic concern and to articulate options to counter Beijing’s threats on the eastern flank. It has done the former by staying away from a project that paid little heed to its sovereignty and territorial concerns. It is time to muster steel and to put together a blueprint for the latter.

China is attempting, vainly, to draw India into a conflict that it believes will prematurely invest it with the label of “first among equals” in Asia. Ironically, Beijing has failed to acknowledge that India does not have to behave like a 10 trillion dollar economy when it is not one — skirmishes, like the one at Doklam Plateau, can be swiftly and aggressively countered by India with little or no loss to its reputation. After all, it would be defending its sovereignty, and in the process, goading China’s smaller neighbours into a similar path. If China wants to be relegated to a disputed regional power, it has only to needle India into a new season of skirmishes and into exacerbating — politically, militarily and diplomatically — Beijing’s multiple land and maritime disputes in Asia.

This commentary originally appeared in NDTV.com.

Global Perspectives: G20 Leaders Summit

Editors note: This global perspectives roundup is a new feature of the Council of Councils initiative, gathering opinions from global experts on major international developments. In this edition, Council of Councils members offer their perspectives on the upcoming G20 leaders summit, which will be held in Hamburg, Germany, on July 7–8.

Tom Bernes, Centre for International Governance Innovation (Canada)

The upcoming G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany, will face new challenges as U.S. President Donald J. Trump makes his first appearance. The forum, which has been promoted by national leaders as their primary platform for international economic cooperation, will have to contend with a U.S. president whose stated policy objective of “America First” stands in direct contrast to the central objective of the G20. A look at the history of the G20 summit speaks to the belief of its members that answers to global challenges must be found through active collaboration. This is likely to be tested in Hamburg. As was witnessed at the G7 and NATO summits in May, surprises are likely.

Since its initial success in forging a response to the global economic crisis of 2008, the G20 has struggled to clearly define a medium-term program that resonates with the global community. Some observers have even questioned whether the G20 can continue to serve as a useful forum that engages the world’s most important leaders.

“Some observers have even questioned whether the G20 can continue to serve as a useful forum that engages the world’s most important leaders.”

Two of the major accomplishments of the G20 will draw close scrutiny in Hamburg as the United States has directly challenged them. The first is the issue of climate change: following U.S.-China leadership, the G20 has supported the Paris Agreement. The United States announced in June its intention to withdraw. The second is the issue of protectionism, which the G20 at every meeting has pledged to resist. Again, the United States has expressed its opposition to such a pledge and imminent decisions by the Trump administration on steel and aluminum risk setting off a trade war. Yet another area of potential concern are the reforms embraced by the G20 to secure greater global financial stability. U.S. decision to roll back much of the Dodd-Frank regulations established after the 2008 financial crisis puts at risk the gains made since the crisis shook the world economy.

How will leaders respond to these issues in Hamburg? A forceful rejection of U.S. positions by the other members of the G20 could give renewed vigor to their efforts to promote a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable global economy. But it would also lead to increased tensions with the United States. Will the G20 gain new momentum through a renewed sense of purpose in response to (and in opposition to) the new U.S. attitude, or will it see a decline in relevance by papering over these fundamental differences?

Sunjoy Joshi and Samir Saran, Observer Research Foundation (India)

Despite the evident geopolitical shifts across the world and the political churn among its member nations, the G20 remains one of the most relevant organizations in the architecture of global governance. Recent global developments both provide an opportunity and pose a challenge for the body if it is to remain influential.

The G20’s most important task is to ensure that it stays true to its core mandate, maintaining global financial stability and managing structural reforms in an inextricably integrated world. The G20 was premised on and motivated by the realization that the “one country, one vote” approach of the United Nations is not the most effective way to respond to critical problems requiring real-time responses. The credit crisis of 2007–2008 demonstrated that certain international challenges need to be addressed efficiently and speedily, which, in effect, catalyzed the institutional preeminence of the G20.

At a time when many members of the G20 are finding themselves trapped by domestic compulsions that are forcing them to rethink the G20’s core mandate, the G20’s temptation to maintain its relevance by anchoring itself in a different agenda needs to be resisted.

The global economy is hardly out of the woods. The G20 is a special-purpose policy forum that was created to respond to globally catastrophic problems by nations that have capacity and wherewithal. This is hardly the time for the G20 to expand its membership by conjuring up new partnerships, such as with African countries. Expanding the group’s partnerships at this juncture would just create another G77—and for what purpose?

“This is hardly the time for the G20 to expand its membership by conjuring up new partnerships, such as with African countries.”

It is also time to recognize that some of the fundamental structural challenges that the G20 is attempting to address cannot be adequately treated unless certain micro-issues are addressed as well. These micro-issues, such as the ongoing transformation in global energy systems, cyberstabilty of financial structures, and the implication of technology on employment and jobs, among others, do need to be on the table, but the temptation to make all issues of global concern a part of the G20 agenda must be resisted. This would only dilute the ability of the G20 to serve its founding purpose. Matters better brought up at the UN General Assembly and/or at other multilateral institutions should not be under the purview of this group.

The G20 should instead narrow its scope to sectors that implicate the global financial and trading systems and additionally only focus on those issues that concern politically disruptive global trends.

The G20 is at a crossroads. It should choose the path that will allow it stay relevant to the core purpose for which its members first came together.

Steven Blockmans and Daniel Gros, Centre for European Policy Studies (Belgium)

Leaders meeting at the G20 summit in Hamburg will try to build on the outcome of the recent G7 summit in Taormina, Italy, and seek agreement on three baskets of issues: economic priorities, including growth, trade, digitalization, jobs, finance, taxation, and corruption; sustainability priorities, including development, climate, energy, health, and gender; and security priorities, including counterterrorism, migration, and refugee flows.

The G20 summit is of particular importance to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who, as chair, will get a last chance to shine on the international stage ahead of the German federal elections in September. But a success is not guaranteed, especially for the second basket, given President Donald J. Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the historic Paris Agreement on climate change. A statement by the other nineteen G20 leaders of their unwavering commitment to the Paris accord seems possible and would be welcome. Unfortunately, reaching consensus on the first and third baskets will also not be easy given the U.S. retreat from its historical multilateral approach toward trade and Russian—and, to some extent, Chinese—intransigence on cybersecurity, corruption, and the rule of law.

This summit will also provide a test of whether Brexit ushers in a new role for the United Kingdom on the global stage. U.S. bilateralism might, on the surface, enhance the UK’s global role, since it is a trusted partner of the United States. But U.S. unilateralism is rendering multilateral venues like the G20 less suitable to serve brexiting Britain’s aims to go global. Moreover, the twenty-seven members of the EU (EU27) will carefully monitor the extent to which the UK, still a member, remains loyal to EU positions.

“But U.S. unilateralism is rendering multilateral venues like the G20 less suitable to serve brexiting Britain’s aims to go global.”

The Hamburg summit provides an opportunity for Merkel and her newfound partner, French President Emmanuel Macron, to position the EU27 as a reference point for those that want to invest in effective multilateralism. In a volatile world, stability and predictability are a premium that Chancellor Merkel and the other standard-bearers of the rules-based EU can provide. How much their leadership can make the Hamburg summit a success is an open question that will shape not just the future of the G20, but also the role of the EU and Germany in the world.

Ye Yu, Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China)

Since its participation in the first G20 summit in 2008, China’s concerns about the forum and global governance have expanded from procedural issues to more substantive ones: the push for equality among members, the redistribution of voting power in international financial institutions, and comprehensive challenges confronting globalization, such as climate change and extremism.

China would like to see G20 countries work together to contain anti-globalization sentiment. A global alliance against the United States is not the best option. Instead, China expects the G20 to pull the United States back toward seeking an enlightened self-interest rather than pursuing an “America First” stance at the cost of all other countries. As the Economist noted, Trump’s economic policies are narrow-minded, out-of-date, takes for granted that “fair trade” means reducing manufacturing deficits, and ignores the destructive challenges the world will confront as artificial intelligence technology advances. The G20 should convey a more comprehensive message about the trends of globalization and shape the public discourse about the limitations of protectionist trade measures.

“China expects the G20 to pull the United States back toward seeking an enlightened self-interest rather than pursuing an “America First” stance at the cost of all other countries.”

China would also like to see G20 members be more supportive of its initiative to spur momentum of globalization. Encouraged by its huge success in launching the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2013 and hosting the 2016 G20 summit, China is more confident and willing to exhibit a more constructive role in global governance, though not by itself. China started the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, along with the AIIB, to offer an alternative approach to globalization. Unlike a top-down approach to negotiating trade liberalization, the Belt and Road Initiative puts a renewed focus on regional and global infrastructure connectivity. China emphasizes the openness of the initiative and calls for all countries to participate according to their own development strategies. Infrastructure has been a G20 priority for quite a few years, but China would like to see more concrete cooperation on projects and less suspicion about its intentions.

Elizabeth Sidiropoulos, South African Institute of International Affairs (South Africa)

This year Germany has made Africa the focus of its G20 presidency. Its anchor initiative is the Compact with Africa, which aims to bring together international financial institutions, bilateral partners, and African countries to create an enabling environment for private investment. Already seven African countries have signed up: Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal, and Tunisia. Driven by the German Finance Ministry, this initiative has received the G20 finance ministers’ political backing in Baden-Baden in March this year.

While this G20 commitment to Africa should be seen in a positive light, concerns have been raised in South Africa about the extent to which it may compete with rather than complement Africa’s own continental initiatives. In addition, its policy prescriptions may be critiqued for their focus on orthodox approaches to economic development, which have not always had the desired results. It is also regarded as shifting responsibility for development assistance from the public to the private sector. Nevertheless, if the G20’s political backing is able to leverage private investment in the countries that have decided to join, this will be an important step in the direction toward creating productive economies that are able to provide decent livelihoods for their citizens.

“While this G20 commitment to Africa should be seen in a positive light, concerns have been raised in South Africa about the extent to which it may compete with rather than complement Africa’s own continental initiatives.”

But G20 issues not specific to Africa are of equal import to the continent. An unequivocal commitment to open trade, although there has been backsliding on protectionist measures for some years, will be crucial for Africa, especially as it tries to build up its manufacturing capacity. Inclusive growth cannot be achieved with closed economies.

Germany has also focused on the need for a framework of norms and standards on the digital economy and e-commerce. However, this may have the unintended consequence of placing greater burdens on African states, making it even more difficult for them to bridge the digital divide. Often, the solutions more so reflect the conditions of the industrialized world and do not sufficiently consider unintended consequences in developing countries. This is the challenge for G20 developing countries as the dynamics among the G7 change. The G20 by its nature is not inclusive; it can, however, build legitimacy provided its leadership in setting agendas and norms reflects not only industrialized countries’ realities, but also those of emerging and developing economies.

Sook Jong Lee, East Asia Institute (South Korea)

The G20 summit in Hamburg is a timely venue for major country leaders to show their commitment to the liberal international order. Following the global disturbance caused by Brexit, U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s “America First” foreign policy has the potential to weaken global governance. Trump’s revival of protectionist trade measures, reduced willingness to support collective security, and decision to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement on climate are threatening the open and liberal order. Now is the time for other major countries to provide additional leadership in response to numerous transnational challenges, including peace and security, terrorism, refugees, and environmental problems.

“Now is the time for other major countries to provide additional leadership in response to numerous transnational challenges, including peace and security, terrorism, refugees, and environmental problems.”

Against this backdrop, German Chancellor Angela Merkel is committed to seizing the opportunity by hosting the summit, with hopes to strengthen the world economy and enhance its stability and resilience through multilateral cooperation. The fifteen agenda items that fall under the broader goals of building a resilient economy, improving sustainability, and assuming responsibility for physical and human security are all worthy of serious attention and require collective effort to make meaningful progress. Chinese President Xi Jinping is expected to assume a greater role by filling the gap left by U.S. retrenchment. French President Emmanuel Macron will likely bring a spirit of liberal progressivism aligned with the current G20 goal of promoting inclusive and sustainable growth. For this summit to prove successful, it is crucial for leaders to demonstrate their solidarity and willingness to combat economic and sociopolitical threats together. At the same time, leaders should develop resilient, cooperative frameworks that can provide members with greater flexibility when weighing domestic policy options.

With seven Asian countries in the G20, China, India, and Japan are expected to increase their roles by assuming responsibilities in line with their respective comparative advantages. Middle powers like South Korea and Indonesia can also promote G20 goals by incorporating them into their regional multilateral initiatives. Asian countries have been relatively insulated from the rise of extreme populism and believe that their futures lie in a more open and interconnected world. Asian members should contribute more to the G20 to further strengthen the forum.

The G20 was created to make economic global governance more democratic and effective. Major states should now assume more responsibility in making the world safer, as well as more economically inclusive and politically harmonious. Each member country must remember that they owe their power and international standing not only to national achievements, but to the global community as a whole. Since no single country can replace the United States, which has provided public goods for the last quarter century, all G20 member should assume their share of the responsibility to manage global challenges.

Fyodor Lukyanov, Council on Foreign and Defense Policy (Russia)

Despite clear political differences among its members, the G20 has been able to send a positive message of global cooperation since its creation twenty years ago. The G20 was founded in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis and upgraded following the 2008 global financial crisis, and the fact that twenty of the most powerful economies came together to seek solutions to instability had its intended effect.

The global economy faces acute problems of a purely political nature. It was feared in 2008 that protectionism would be the spontaneous reaction of several governments; it is now the deliberate and official policy of the most powerful member of G20, the United States. Although one can argue that the Trump administration is not consistent in its claims and deeds, it is vocal and consistent on economic issues. If the United States proclaims “America First,” it is just matter of time until the rest of the world will turn to more mercantilist thinking as well.

It remains an open question the extent to which member states will be able to agree on anything at the upcoming summit. G20 summits have always been overshadowed by various crises, but the number of controversies in which member states are now involved is remarkable. Recent escalation in the Gulf has added another nuance to the already bleak picture. There is a chance that this G20 will have an impact that is the opposite of what its 2008 iteration had: it could be a disappointing demonstration of disagreement on all fronts. Germany, which is deeply committed to good governance, will no doubt do its best to refocus G20 commitment on global cooperation—particularly the Paris Agreement—but Chancellor Angela Merkel has no magic wand.

“It remains an open question the extent to which member states will be able to agree on anything at the upcoming summit.”

While Russia hasn’t been the biggest promoter of free trade and openness, it is now concerned by looming protectionism and would like to keep a moderately liberal global economic system in place. Moscow will also use this opportunity to communicate with the many international leaders in attendance. Most public attention will be given to the prospective meeting between Presidents Vladimir Putin and Donald J. Trump, but no positive outcome is expected. Trump will be unable to move on U.S.-Russian relations, even if he would like to, because Russia’s policy remains toxic in U.S. domestic politics. His handshake with Putin, though, will no doubt cause another political tsunami in Washington, which will further undermine their prospects for interaction.

Heribert Dieter, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Germany)

The G20 set high targets for itself in the early stages of the 2008 global economic and financial crisis, but, despite grand declarations, it has achieved relatively little. Risks in the financial markets have risen rather than fallen, and the G20 countries have no coherent strategy. For now, the United States continues to take a unilateral approach, not taking into account the preferences of other G20 states. The European Union is pursuing its own financial policy, which it has not coordinated with those of the other G20 countries.

The early, resolute G20 announcements were followed by only half-hearted attempts to regulate financial markets more strictly. In the midst of the crisis, expectations arose that there would be coordinated international supervision of financial markets. That concept has not been implemented. Today, G20 governments are unable to agree on common rules. Hopes for a new global financial architecture have been shattered.

There are many reasons why the G20 has not succeeded in providing a common set of financial rules. The preferences of G20 countries are divergent; therefore, the group has been unable to accomplish its core mission.

Equally poor has been the performance of the G20 in promoting a liberal regime for international trade. The declarations of earlier summits were never matched by a liberal trade policy among the G20’s members. Many important economies demonstrated a robust interest in trade that was “fair” rather than “free.” A spirit of protectionism characterized the trade policy of some G20 countries, and the advent of the Trump administration has made the departure from an open multilateral trading system more visible than before. Discrimination and protectionism are once again features of the trade policies of G20 countries.

The Hamburg summit will not result in any major agreement on joint economic policies. For the time being, G20 governments differ on fundamental issues of global governance. Neither on finance nor trade, let alone climate change, will Hamburg deliver any significant improvement over the status quo. Worse, there might be open conflict over protectionist measures the Trump government might implement.

“For the time being, G20 governments differ on fundamental issues of global governance. Neither on finance nor trade, let alone climate change, will Hamburg deliver any significant improvement over the status quo.”

At the same time, the position of Germany, the host, has been severely weakened by the failure of the Merkel government to acknowledge the harms Germany’s enormous current account surpluses has had on other economies. Berlin’s unwillingness to implement measures that would reduce the surplus—for instance, a temporary tax cut—undermines the credibility of its calls for enlightened multilateral cooperation.

Yasushi Kudo, Genron NPO

The arrival of President Donald J. Trump’s administration is expected to limit the ability of the G20 to address global issues through international cooperation. President Trump’s avowed “America First” policy and his preference for bilateral deals will continue to undermine the raison d’etre of the G20, which supports multilateralism by sharing the burden of leadership among its member countries. In addition, overt and covert moves by superpowers to bolster their influence by making use of the fragile international environment are likely to erode the foundation of the established frameworks that have hitherto sustained the world order.

“The arrival of President Donald J. Trump’s administration is expected to limit the ability of the G20 to address global issues through international cooperation.”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel apparently intends to make “open markets, and free, fair, sustainable, and inclusive trade” a key focus of the summit this year. Given the instability of the international order, it may not be meaningless for the leaders of the world’s major economies to come together for dialogue and impress upon the world that they are making continuous efforts for the common good. Regrettably, there is no other positive meaning to be found in the present state of the G20, and this year’s summit will likely achieve nothing substantial. As shown by the wording of the communiqué issued at the G7 summit in Italy in May, the G20 will be another political show that uses ambiguous rhetoric to conceal instability and potential confrontations.

That said, the G20 forum remains important. Globalization, the maintenance of a liberal international order, and multilateral cooperation are of vital importance to the common interests of the world. At a time when there is a desperate need to rectify inequalities and instability, the role of the G20 will be much larger than before. Such being the case, it is becoming necessary to solidify cooperation among G7 members and other democratic states that share fundamental values in order to ensure that the G20 can continue to carry out its role.

The presence of the G7, whose members share the universal values of freedom, democracy, and international cooperation based on multilateralism, is vital for the reinforcement of global governance and the preservation of a liberal international order. Moreover, the G7-initiated global economic governance and international financial system form the foundations of global governance. Unified G7 attempts to take initiative in this area in the long term may hold the key to maintaining global stability. Indeed, the significance of the G7 democracies’ concerted endeavors to strengthen global governance should not be underestimated.

Original link is here