Category Archives: Water / Climate

Setting a path to green, resilient and inclusive development

Co-Authored with Mari Elka Pangestu

By investing now to build a green, resilient and inclusive economy, countries can turn the challenges of COVID-19 and climate change into opportunities for a more prosperous and stable future.

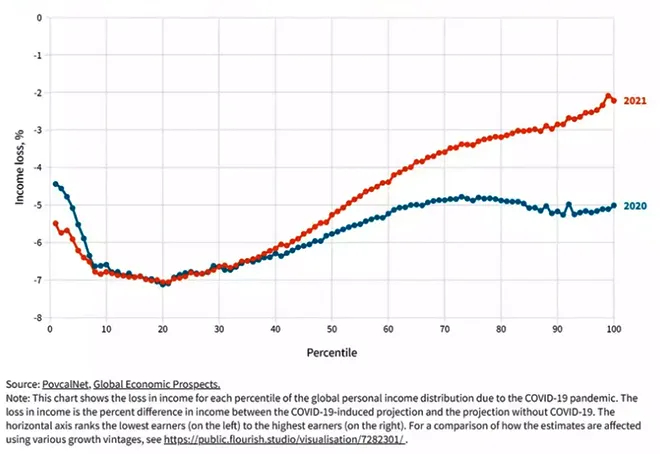

The decade following the 2009 global financial crisis was characterised by growing structural weaknesses in developing countries, which have been further aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, worsening poverty and inequality. These weaknesses include slowing investment, productivity, employment, and poverty reduction; rising debt; and accelerating destruction of natural capital. The pandemic has already pushed over 100 million more people into extreme poverty and worsened inequality. The effects of climate change are expected to push an estimated additional 130 million people into extreme poverty by 2030.

COVID-19 and climate change have starkly exposed the interdependence between people, the planet, and the economy. All economic activities depend upon ecosystem services, so depleting the natural assets that create these services, eventually worsens economic performance.

The decade following the 2009 global financial crisis was characterised by growing structural weaknesses in developing countries, which have been further aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, worsening poverty and inequality.

Figure 1: Global income losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic

A business-as-usual recovery package that neglects these interlinkages would not adequately address the complex challenges that confront the world nor its structural weaknesses and would likely result in a lost decade of development. Targeting socioeconomic, climate change and biodiversity challenges in isolation is likely to be less effective than a coordinated response to their interacting effects. A continuation of current growth patterns would not address structural economic weaknesses and would erode natural capital and increase risks that affect long run growth. As the depletion of forests, oceans, and other natural assets worsen, the cost of inaction is becoming more expensive than the cost of climate action and it is the poor and vulnerable who are most disadvantaged by it.

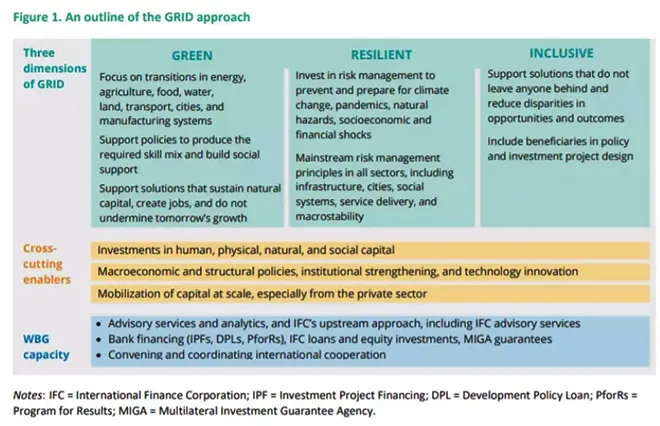

The GRID approach

The solution is to adopt a Green, Resilient and Inclusive Development (GRID) approach that pursues poverty reduction and shared prosperity with a long-term sustainability lens. This approach sets a recovery path that maintains a line of sight to long-term development goals; recognizes the interconnections between people, the planet, and the economy; and tackles risks in an integrated way. Research from the University of Oxford, World Economic Forum and Observer Research Foundation has all shown that a green recovery will not just be beneficial for combating climate change but also offer the best economic returns for government spending and yield development outcomes. The GRID approach is novel in two respects.

First, though development practitioners have long worried about poverty, inequality and climate change, the GRID approach pays particular attention to their interrelationships and thus, on the cross-sectoral nature of critical development policies. Second, achieving GRID implies simultaneously and systematically addressing sustainability, resilience and inclusiveness. GRID is a balanced approach focused on development and sustainability and tailored to each country’s needs and its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) objectives. Such a path will achieve lasting economic growth that is shared across the population, providing a robust recovery and restoring momentum on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Research from the University of Oxford, World Economic Forum and Observer Research Foundation has all shown that a green recovery will not just be beneficial for combating climate change but also offer the best economic returns for government spending and yield development outcomes.

Recovering from COVID-19 with GRID

The pandemic has inflicted a particularly harsh blow on developing economies. Most urgently, a fast and fair vaccine rollout is critical to an L-shaped recovery. Vaccine access and deployment presents challenges unprecedented in scale, speed and specificities, which will require strong coordination.

Looking ahead, setting a path to GRID will require urgent investments at scale in all forms of capital (human, physical, natural, and social) to address structural weaknesses and promote growth. Special attention is needed on human capital development to rebuild skills and recover pandemic related losses, especially amongst marginalised groups. While the pandemic has amplified the challenges of providing education for all, it has also highlighted how disruptive and transformational technologies can be leveraged in addition to traditional in person learning to help education services withstand the unique pressures of this time.

Recovery packages are an opportunity to prioritise investments in the infrastructure needed to develop and roll out transformative technologies.

Women must be at the center of the GRID agenda as powerful agents of change. Education for girls, together with family planning, reproductive and sexual health, and economic opportunities for women will accelerate the green, resilient and inclusive dimensions of development.

Technology and innovation will play an essential role in promoting low carbon growth. Recovery packages are an opportunity to prioritise investments in the infrastructure needed to develop and roll out transformative technologies.

One takeaway from Glasgow has been that securing green finance at scale will be essential for the GRID agenda. However, developed countries found it difficult to secure the necessary funding for developing countries to implement the green transition to sustainable and equitable development.

But there may be a silver lining. The global economy is awash with excess savings estimated at around $3.9 trillion that are earning negative or low returns and there are $46 trillion of pension funds in search of reasonable returns. The low carbon transition may offer an opportunity for investors, especially as the returns to green investments begin to exceed investments in more conventional technological choices.

Necessity and urgency of systemic investments and transformations

Transformational actions will be needed in key systems — for example, energy, agriculture, food, water, land, cities, transport and manufacturing — that drive the economy and account for over 90 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Without significant change in these sectors, neither climate change mitigation nor sustained and resilient development are possible. Such a transition, by addressing economic distortions, will promote greater economic efficiency and reduce adverse productivity and health impacts, leading to better development outcomes.

Domestic resource mobilisation can also be increased by enhancing tax progressivity, applying wealth taxation, and eliminating tax avoidance. There is also a need for greater selectivity and efficiency in spending.

But the fruits of the transition may not be evenly distributed and will require a range of social and labour market policies that address adverse impacts, safeguard the vulnerable and deliver a just transition. The GRID approach, therefore, supports a transition to a low carbon economy while considering countries’ energy needs and providing targeted support for the poorest.

Significant reforms of fiscal systems will be needed to mobilise domestic resources and finance the transition. Taxes on externalities are a large and unused source of potential revenue, which can create incentives for the private sector to invest in more sustainable activities. Domestic resource mobilisation can also be increased by enhancing tax progressivity, applying wealth taxation, and eliminating tax avoidance. There is also a need for greater selectivity and efficiency in spending.

A strong private sector involvement will be needed. The scale of investment needed far exceeds the possibilities of the public sector. Reforms are needed to remove constraints to private investment in appropriate sectors and technologies. Thus, at the country level, a strong partnership and dialogue between the public and private sector is urgently needed. And further developing and implementing green financial sector regulation, such as reporting standards and green taxonomies, can help harness investors’ increasing appetite for sustainable investments, which offer both measurable impacts on the environment and society.

However, sustainable and substantial flows of finance across borders will need to supplement domestic efforts. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) must focus on catalytic and transformational investments in priority areas to develop green, inclusive and resilient project pipelines that support economic growth, and job and income generation. On this front, MDBs can help lower risks for private capital through guarantees and blended finance. But at the end of the day the most effective way to attract private capital is through policies that correct distortions that render environmental destruction profitable.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) must focus on catalytic and transformational investments in priority areas to develop green, inclusive and resilient project pipelines that support economic growth, and job and income generation.

Climate change is a reality shaping lives as we speak and not a distant mirage that will materialise only in the future. From Pacific Island nations facing rising sea levels to the Sahel region struggling with longer dry seasons, climate change is changing lives of the poor and vulnerable across the world. The future for the world’s climate vulnerable groups will remain bleak unless we transform policy and economic thinking and secure the financing that is needed.

Countries face a historic opportunity to establish a better way forward. Despite the damage wrought by the pandemic, the exceptional crisis response offers a unique opportunity for a “reset” that addresses past policy deficiencies and chronic investment gaps. Crisis related expenditures can be used to invest in new opportunities, such as accelerating digital development, an expansion of basic service provision, improvements in regional supply chains, strengthening ecosystems services, and policies to catalyze job creation in growth sectors. Private sector dynamism and innovative financing will need to power the recovery and to create economic growth and employment through investment and innovation. Public-private partnerships and key upstream policy reforms can spur private investment (including FDI), support viable firms through restructuring, and enable the financial system to support a robust recovery through the resolution of non performing loans.

Bridging the gap: Addressing international barriers to climate action projects in the developing world

ORF, Issue Briefs and Special Reports, Dec 12, 2017

Original link is here

this report is part of the Observer Research Foundation’s “Financing Green Transitions” series which aims to find potential linkages between private capital, in all its forms, and climate action projects. The series will primarily examine domestic and international barriers to private capital entry for mitigation oriented climate projects, while also examining potential avenues for private capital flow entry towards adaptation and resilience projects.

Read the series: Financing Green Transitions

Introduction

The fight against climate change is at an inflection point. Despite a myriad of actors attempting to ensure that the world is not left in a ruinous state for future generations, linkages between the release of greenhouse gases and the rise in global temperatures are still ignored by certain stakeholders. The cavalier attitude of these important actors has had a detrimental impact on the state of financial flows towards climate action projects especially in the developing world.

| Box 1: The politics of climate finance flows

As discussed in an earlier issue brief in ORF’s Financing Green Transitions series, the industrialised nations of the world made a pledge under the 2015 Paris Accords to provide $100 billion in annual funding for climate action projects in developing countries. The developed world has yet to live up to its commitment, however, with estimates showing current annual flows totalling $50 billion. The apparent lack of commitment towards climate finance flows is not the sole area of concern. The politics behind the calculation and categorisation of this estimate remains a point of contention in the developing world. While the language pertaining to the $100 billion of funding within the Paris Agreement is vague, what was envisioned at the inception of the funding conversation was a supplementary stream of financial flows. Many developed countries, however, have simply reallocated the funds within their development aid budgets in order to meet their obligations. This has had a significant detrimental effect on the achievement of important sustainable development goals across the world. In addition to their supplementary nature, the flows were also intended to be unconditional in their original form. A closer examination of the numbers, however, shows that 25 percent of the $50 billion that is being provided, comes in the form of loans from multilateral development banks. Given that loans, by their very nature, must be paid back with interest, certain parties have protested their categorisation as “assistance” for climate action efforts. The feeling amongst some in the third world is that the $50 billion estimate is an exaggeration, bolstered by creative accounting and wilful incongruity. |

While a shortfall in the funding pledges made to the developing world through public financing seems inevitable, [i] there remain possible avenues to make up for this deficit through the mobilisation of private capital. Yet, despite repeated demonstrations of the sizeable returns that can be reaped by funding climate action projects, [ii] the institutions overseeing much of the world’s private capital have been wary of making such investments in developing economies.

An examination of certain domestic hurdles preventing private capital investments in the developing world, has been conducted in the first part of this series. It is important, however, to also examine the impediments on a global scale. This issue brief, part of Observer Research Foundation’s Financing Green Transitions series, will examine the main international barriers dissuading private capital investment in climate action projects — namely institutional investor practices, foreign exchange risk, and international financial regulations.

International institutional investor practices

Any conversation pertaining to private capital flows for climate action projects, must begin with institutional investors. Institutional investors (a catch-all term for large asset managers such as pension funds and insurance companies) control close to $100 trillion of the world’s wealth, [iii] and are in many ways the key to unlocking private capital flows for climate action projects.

Given the various stakeholders they must answer to, institutional investors tend to be conservative in their investment approaches, which acts as a deterrent when attempting to steer cash flows towards climate action projects. An example of this can be seen in the cautious approach taken by institutional investors with regards to illiquid investments. [iv]Most of the private capital in the world lies in the hands of pension funds and insurance companies, who are encumbered with large annual liabilities in the form of pension obligations and insurance pay-outs. This limits the amount of exposure that such asset owners are willing to have towards large projects involving heavy capital expenditure in PPE [v] which tend to be largely illiquid as an asset class. Investors prefer to put their funds towards instruments that can be converted into cash quickly, such as bonds and equities.

The cautious nature of institutional investors is further manifested in their project evaluation criteria. Traditionally, institutional investors do not evaluate investments on a case by case basis, preferring to apportion their funds to asset managers who have the capacity and expertise to carry out the necessary analysis and due diligence. In order to invest in climate action projects, institutional investors have to either build up sector-specific expertise internally or divert their funds towards specialists with existing capacity. Building up internal expertise is a time consuming and expensive process, and the global marketplace has a dearth of financial intermediaries who specialise in climate action projects. The evaluation of the performance of financial intermediaries is also problematic, given the absence of extensive track records in the nascent industry [vi].

The conservative risk management practices of institutional investors often act as a barrier against climate action investments, as well. In order to diversify their risk portfolios, pension funds and insurances companies tend to invest across a variety of asset classes, with set limits for the proportion that can be allocated towards each sector [vii]. Climate actions projects, and more specifically renewable energy projects, tend to be classified under the energy or infrastructure sector, and as such are often crowded out by more traditionally accessible investments that institutional investors are familiar with.

This problem is exacerbated by the orthodox perceptions and attitudes of institutional investors with regard to climate action project and developing economies. Pension funds and insurance companies tend to have outdated views with regards to climate action projects especially with regards to technology risks, payment risk, and returns. Institutional investors also rely heavily on risk ratings to inform their investment decisions, which is problematic due to the unreliable metrics and evaluation methodology used to evaluate many climate action projects. Risk ratings are also often constrained by the sovereign debt rating of a country – in many cases a climate action project rating cannot be higher than the rating of the country, regardless of the financial viability of the investment.

Foreign exchange rate

While internal factors play a part in hindering international institutional investor flows, there are also external factors that must be considered. Amongst the largest hurdles for any investor attempting to invest in the developing world is the risk associated with domestic currency fluctuation. Climate action projects can be affected by foreign exchange risk during any stage of the value chain, but are especially vulnerable to risk in the post construction phase. To illustrate how foreign exchange risk can affect investors, it is perhaps best to take the example of a solar plant project.

A solar project starts with the purchase of the land on which the plant will be built. Unfortunately, in many developing nations, the property acquisition procedure is time consuming, with costly delays that can take months or even years to be resolved [viii]. Unexpected upticks in the foreign exchange rate during the land acquisition period can lead to significant variance in investor expense, with cost increases potentially reaching millions.

The acquisition of land is usually followed by the procurement of materials — namely photovoltaic panels. China holds a near monopoly in the manufacturing of solar panels, [ix]which means that investors have to factor in the possibility of fluctuations in the Reminbi, as well as the local currency. Foreign exchange risk associated with the purchase of solar panels is not limited solely to developing nations. Recently, investors in a solar plant in Cambridgeshire County had to account for a $645,000-increase in the cost of Chinese based panels as a result of the unexpected depreciation of the Pound, following the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. [x]

Putting aside the procurement of land and solar panels, foreign exchange risk continues to exist during other phases of a solar project – payments to local contractors, transport fees, and government levies must all be made in the local currency. The largest exposure to foreign exchange risk for international investors, however, is in the post construction phase. Barring certain exceptions, power purchase agreements delineate payments in local currencies, which leaves investors susceptible to foreign exchange risk for the length of the contract. The possibility of currency fluctuations over a long time frame nullifies one of the key attractive characteristics of a solar energy project — guaranteed, predictable cash flows over a fifteen to twenty year period.

| Box 2: Real world example – Brazil’s currency crisis

In late 2014, Brazil awarded nine contracts to developers for the construction of 900 MWs of solar power. A global downturn in oil prices caused the value of the Brazilian Real to drop dramatically over the next two years. As a result of the currency depreciation, the contracts that were signed in 2014 generated 36-percent less revenue for developers by 2016. Eight of the nine investors ended up dropping out of the agreements, citing a lack of continued financial viability for the projects. |

The unpredictability of the revenue flows can lead to severe consequences that affect more than just the status of the investment. Given the sizeable capital needed for a solar project, investors often have to borrow up to 70 percent of the start-up costs from banks. If currency fluctuations are dramatic enough, investors can face the possibility of defaulting on loan or interest payments, [xi] which can lead to ripple effects for an investor’s entire portfolio. The starkest example of the consequences of changes in the foreign exchange rate can be illustrated by examining the case of Brazil.

While foreign exchange risk is problematic for investors, it is not a new phenomenon and affects a number of sectors. It is important to note, however, that the electricity sector is more susceptible to the effects of currency fluctuation — they cannot raise prices or renegotiate the rates dictated under the power purchase agreements to cover potential losses. Additionally, financial methods available for the mitigation of foreign exchange risks for other sectors are not necessarily applicable for renewable energy or other climate action projects. One simple solution employed in certain sectors, for example, is to use domestic banks to procure loans in the local currency. As has been pointed out, however, long-term debt for climate action projects is not available in many developing economies. Alternative financial strategies which can hedge against currency risk in other sectors, are also not always viable for developing economy climate action projects. The expenses associated with such instruments can raise the interest rates charged by international banks by six to seven percent, [xii] making previously profitable projects unattractive.

International banking regulations

While internal practices and foreign exchange risk play a role in limiting private capital flows for climate action projects, the largest hurdle for green investments in developing countries comes in the form of international banking regulations. Due to the large capital requirements for climate action projects, up to 70 percent of start-up costs usually originate from bank loans [xiii]. The credit crisis of 2007-2008 has led to stricter controls being imposed on bank loans, making it more difficult for investors to access the funding needed to get a project off the ground. The problems that the norms cause for renewable energy investments can be explained by examining two of the three ratios dictating the amount of cash or near cash assets a bank must keep on hand — the capital requirement ratio and the liquidity coverage ratio.

| Box 3: A brief overview of the Basel norms

The Basel norms were initially conceived in 1988, by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS)[1] as a mechanism designed to prevent banks from insolvency issues caused by defaults of risky assets. The norms required banks to keep a certain percent of its overall investment portfolio on hand in order to prevent the bank from going out of business in the case of widespread failure of loans and investments. These requirements proved to be insufficient during the credit crisis in the mid 2000’s to late 2000’s, however, leading to a renewed examination of international banking regulations and the subsequent release of a new version of the Basel norms. The latest iteration of these macro prudential regulations, referred to as Basel III, were introduced in 2011 with subsequent amendments added in 2013 and 2014. |

A holdover from the previous version of the Basel norms, the capital requirement ratio dictates the amount of cash that a bank must keep on hand, by factoring in how risky the investment practices of the institution are. Each investment made by the bank is assigned a risk weighted percentage, depending on its characteristics – certain government bonds for example are considered to have almost no risk associated with them and are thus assigned 0 percent. The value of each investment is then multiplied by its risk percentage, after which all the values are collated to produce the bank’s Risk Weighted Average (RWA). According to Basel III, banks must keep between six to ten percent of the value of their RWA on hand [xiv].

The core function of private banks, like any other business, is to make a profit and any cash that they have to keep on hand to meet the capital requirement ratio cannot be invested in revenue related activities. Banks, therefore, have two options — reduce the amount of cash they have to keep on hand by making investments that are considered less “risky” or ensure that the returns they get from the “risky” investments are high enough to justify the increased cash they will have to keep on hand.

While investors view the capital requirement ratio as a hindrance, it is the addition of Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) in the Basel norms that has caused the largest amount of consternation amongst institutional actors. Intended to act as a counter measure against the factors that caused the credit crisis of 2008, the LCR forecasts how a bank’s business operations would be affected by a large scale financial crisis. The projection assumes that the amount of cash received from investments will drop during the “stressed period” while the amount of cash extracted by customers will increase. The extent to which cash receivables are meant to drop and cash withdrawals are expected to increase is dependent on certain characteristics – for example, 10 percent of deposits made by individuals and small businesses are expected to be withdrawn. Large financial institutions, on the other hand, are projected to withdraw 100 percent of their deposits in a stressed scenario [xv]. In order to fulfil the requirements of the liquidity coverage ratio, banks must keep on hand cash or assets that can be easily converted into cash (referred to as High Quality Liquid Assets) to meet all obligations that might occur during a 30 day “stress period.”

The inclusion of the leverage coverage ratio in Basel III has had two major effects on banking lending processes. First, banks have started to show a preference for the types of deposits that are expected to have less of an effect on cash outflows during a financial crisis, such as small businesses. Secondly, banks have moved away from lending to long term projects in favour of more short-term liquid assets in order to meet the requirements of the liquidity coverage ratio.

The capital requirement ratio and the liquidity coverage ratio are problematic for investors attempting to access debt for investments in either climate action projects or developing countries. The high risk profiles assigned to both types of projects by the majority of rating agencies lead to a higher capital requirement burden for banks who pass the cost on by asking for significantly higher interest rates for any debt provided to climate action projects in developing countries.

The long life span and illiquid nature of climate action projects also impacts the liquidity coverage ratios of banks, leading to significantly higher interest payments on loans made to finance said projects. The high cost of international debt financing, combined with the inability to access debt from domestic banks in most developing economies, has had a considerable negative impact on climate action projects with certain analyses showing a 40 percent drop in institutional investor flows as a result of the implementation of Basel III [xvi].

The way forward

The international issues that have been discussed in this brief play a significant role in hindering private capital flows towards developing economies. The conservative investment practices of international institutional investors create restrictive internal barriers that are difficult to overcome but can be done, over time, through capacity building measures. Foreign exchange risk can result in sizeable liabilities for certain types of climate action projects and while the risk cannot be hedged using traditional mechanisms, policies such as dollar denominated tariffs or government backed hedging facilities are possible ways to mitigate it. The restrictive controls that are placed on long tenured, risky projects such as renewable energy make it difficult to access international debt financing, but policies reclassifying the risk associated with such projects could make them more attractive for creditors.

The Observer Research Foundation over the next twelve months will release a set of reports as part of their Financing Green Transition series looking at potential methods to increase the flow of private capital investments for climate action projects in developing countries. The reports will include an examination of the risk perceptions of European Institutional Investors with regards to renewable energy projects; an econometric analysis of the benefits of credit enhancement mechanisms by Multilateral Development Banks; a methods report aimed at creating a transparent and publicly accessible ratings evaluation system; and a feasibility study examining the viability of greening “Basel” through alterations in their risk calculations.

[i] Joe Ryan, “G-20 Poised to Signal Retreat From Climate-Change Funding Pledge,” Bloomberg.com, March 09, 2017, accessed July 01, 2017,

[ii] Renewable Infrastructure Investment Handbook: A guide for Institutional Investors. December 2016. Accessed July 1, 2017.

[iii] “Institutional Investors: The Unfulfilled $100 Trillion Promise” June 18, 2015. Accessed July 01, 2017.

[iv] Nelson, David, and Brendan Pierpoint. The challenge of Institutional Investment in Renewable Energy. March 2013. Accessed July 1, 2017.

[v] Plant, Property and Equipment

[vi] Nelson, David, and Brendan Pierpoint. The challenge of Institutional Investment in Renewable Energy. March 2013. Accessed July 1, 2017.

[vii] Nelson, David, and Brendan Pierpoint. The challenge of Institutional Investment in Renewable Energy. March 2013. Accessed July 1, 2017.

[viii] India: Delays in Construction Projects. January 24, 2017. Accessed July 1, 2017.

[ix] Fialka, John. “Why China Is Dominating the Solar Industry.” Scientific American. December 19, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2017.

[x] “Currency Risk Is the Hidden Solar Project Deal Breaker.” Greentech Media. May 05, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2017.

[xi] Reaching India’s Renewable Energy Targets Cost Effectively: A foreign exchange hedging facility. June 2015. Accessed July 19, 2017.

[xii] Chawla, Kanika. Money Talks? Risks and Responses in India’s Solar Sector. June 2016. Accessed July 1, 2017.

[xiii] Renewable Energy Project Financing. Accessed July 19, 2017.

[xiv] Bank of International Settlements. Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems. December 2010. Accessed July 19, 2017.

[xv] Bank of International Settlements. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools. January 2013. Accessed July 19, 2017.

[xvi] The empirics of enabling investment and innovation in renewable energy. May 24, 2017. Accessed July 19, 2017.

How India and the US can lead in the Indo-Pacific

the interpreter, Friday, August 18, 2017

Original link is here

Although the Pacific and Indian Oceans have traditionally been viewed as separate bodies of water, India and the US increasingly understand them as part of a single contiguous zone. The US Maritime Strategy (2015), for example, labels the region the ‘Indo-Asia-Pacific’, while Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Donald Trump referred to it in their recent joint statement as the ‘Indo-Pacific.’

India and the US have a strong stake in seeing this unified vision become a reality. It would increase the possibility that they could promote liberal norms and structures such as free markets, rule of law, open access to commons, and deliberative dispute resolution not just piecemeal across the oceans, but rather in a single institutional web from Hollywood to Bollywood and beyond. Given the region’s economic and demographic dynamism and the importance of its sea lanes to global trade and energy flows, the significance of such a liberal outcome cannot be overstated.

India and the US have publicly called Indo-US cooperation the lynchpin of their strategy in the region. But it has not been as productive as it could be. Robust maritime cooperation between the two countries began only after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which demonstrated the increasing capabilities of the Indian Navy. Even since then, however, India has generally not been a proactive partner, and in fact often has refused US offers of cooperation. In some cases it appears to have done so out of concern for Chinese sensibilities. For instance, a senior Indian official recently suggested that New Delhi had rejected numerous US Navy requests to dock ships at the Andaman Islands in part because of China’s ‘displeasure’ about the US presence in the Indian Ocean.

The US, for its part, has repudiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership, once touted as the economic bedrock of its Asia strategy, and is distracted by Russian machinations in Europe and the Middle East, and the continuing war in Afghanistan. In addition, bureaucratic divisions between US Central and Pacific Commands hamper Indo-US cooperation west of the Indo-Pakistan border, where the US-Pakistan relationship dominates.

China has taken the real initiative in constructing a wider Indo-Asia-Pacific region. Its strategy is multi-faceted. China erodes the autonomous politics of sub-regional groupings, using its economic leverage to create differences amongst ASEAN members, denying strategic space to India through economic projects like the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, and using North Korea to limit Japanese and US influence in East Asia. China also employs institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, construction and finance projects linked to the Belt and Road Initiative, and trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership to create a network of physical infrastructure and strategic dependence across the region. This network includes ports in Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Pakistan; oil and gas projects off the coast of Myanmar; and a military base in Djibouti.

China’s strategy will increasingly put it in a position to create institutions, generate norms, and make and enforce rules in a zone stretching from East Asia to East Africa. Although Chinese preferences are uncertain, it seems unlikely that such a Sino-centric model will adhere to the liberal norms and practices that the US and India hope will take root in the Indo-Asia-Pacific. Indeed, Chinese behaviour, which includes territorial reclamations, rejection of maritime-dispute arbitration, establishment of an air-defence identification zone, and confrontations such as the ongoing Sino-Indian standoff over borders in Bhutan, suggest an authoritarian approach to the region.

Recognition of these dangers has been a central driver of US-India strategic cooperation. If the US-India partnership is to confront them effectively, however, the two countries must think more creatively about how better to work together, particularly in the defence sphere.

The core elements of Indo-US defence partnership include movement toward the adoption of common platforms and weapons systems as well as shared software and electronic ecosystems; closer cooperation on personnel training; and the convergence of strategic postures and doctrines. These elements can realise their full potential only if the two countries enable large-scale US-India data sharing, which will significantly enhance interoperability between their two militaries. This, in turn, will be possible only through the signature of the so-called Foundational Agreements, which provide a legal structure for logistical cooperation and the transfer of communications-security equipment and geospatial data.

India has historically resisted signing these agreements. But many Indian objections are rooted in domestic political calculations rather than substantive strategic concerns. Moreover, with the 2016 signature of the logistics agreement known as LEMOA, India may have crossed an initial hurdle. Perhaps a concerted effort to reconsider objectionable language, without fundamentally altering their substance, could make the remaining agreements palatable to Indian leaders. Given the impact this would have on India’s ability to cooperate with the US to meet the Chinese challenge, it could get serious consideration in New Delhi.

India and the US can take a page from China’s military strategy. Much has been made of the dangers of China’s anti-access/area denial capabilities. But India can also leverage its geography to impede access to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. For example, with US assistance, it could transform the Andaman and Nicobar islands into a forward-deployed base for surveillance and area-denial assets. This would exploit natural Indian advantages, hamper China’s ability to expand its reach and consolidate its gains across the region, and not require India to shoulder unrealistic burdens in far-off areas of operation.

India and the US also need to take a diplomatic and developmental approach to the region that is geographically holistic and offers credible alternatives to Chinese projects; they should not adopt disparate strategies east and west of the Indian Ocean, or promote projects that are rhetorically attractive but lack financial and diplomatic ballast. Recent announcements of pan-regional projects such as the Indo-Japanese Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, and the revived US Indo-Pacific Economic Corridor and New Silk Road initiative, are welcome developments. It will be essential to ensure that these projects continue to receive adequate support, and to create synergies between them that can help to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Additionally, India must cultivate political relationships in its close neighborhood with countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, the Maldives and the ASEAN members to project its influence into the Indian Ocean. Regional states have already begun to fall prey to China’s ‘debt trap’ diplomacy. For instance, Sri Lanka has struggled to service its debt owed to China for the construction of the US$1 billion Hambantota port, which has put the government in Colombo under considerable political and economic duress. India should offer its neighbors sustainable infrastructure projects and strong economic incentives that can provide an alternative. These efforts will be more likely to succeed if the US, Japan and Australia support them diplomatically and through co-investment in economic ventures.

None of these measures will be easy to implement; they will face resource constraints, political opposition, and strategic competition. But the stakes – who gets to construct the legal, economic, and military architecture of an integrated Indo-Pacific region – are enormous. Without bold policy from the US and India, the answer will be China.

The finance sector must sign the Paris pact

live mint, Dec 28, 2016

Original link is here

Without increased climate funding to the global South, the poor will end up underwriting a green future for a privileged few

The infrastructure gap, global financial sustainability, and a green future are recognized to be common global problems. Photo: Bloomberg

The Paris Agreement on climate action has an Achilles heel: the lack of a buy-in from the financial community. This absent and crucial signatory will need to play a significant role if any ambitious response to climate change has to be achieved.

This is easier said than done. “Sustainability” in financial market jargon has a very different meaning to when it is used in development-speak. In the market, this term largely disregards issues pertaining to employment generation, poverty eradication, inclusive growth and environmental considerations. Instead, it is monomaniacal in enhancing the “basis points” of the returns it generates for the community it serves—with only perfunctory interest in the “ppm (parts per million)” of carbon (mitigated or released) associated with the deployment of finance, or the human development index (HDI) effects of investments.

The regulatory responsibilities and the fiduciary duties that drive the functioning of this community are focused mostly on protecting the interests of investors and consumers (of financial instruments and banking services) by de-risking the financial ecosystem. Together, these present two specific hurdles, both of which make it difficult for the world of money to serve the ambitions of the Paris Agreement. The first hurdle pertains to geography, more specifically political geography. And the second pertains to democracy, more specifically the politics of decision making within institutions that shape and drive global financial flows.

Together, they have deleterious consequences. For instance, the major chunk of climate finance labelled as such finds it tedious to flow across borders. Thus, it is mostly deployed in the locality of its origin. This tendency is even starker for financial flows from the developed world to the developing and emerging world. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—Climate Policy Initiative (OECD—CPI) study found that “public and private climate finance mobilized by developed countries for developing countries reached $62 billion in 2014”. A separate study by CPI estimated that global flow of climate finance crossed $391 billion in the same year—implying that only about 16% of all flows moved from developed to developing countries.

This represents the most significant “collective action problem” that confronts the global community on the issue of climate change. While there is a near universal recognition that a) climate change is a global commons problem, b) the least developed countries are likely to be most affected, and c) significant infrastructure will need to be developed in emerging and developing countries to improve their low standard of living, the flow of money is (not surprisingly) blind to each of these. It recognizes political boundaries, responds to ascribed (and frequently arbitrary) ecosystem risks within these boundaries and flows to destinations and projects that enhance returns—as it was meant to.

The travails of this constrained flow of capital do not end here. In a discussion paper published by the climate change finance unit within the department of economic affairs at the Union ministry of finance, it has been highlighted that even this modest cross-border flow, which also accounts for pledges and promises made, does not adhere to the “new and additional” criteria. Flows of conventional development finance and infrastructure finance are on occasion reclassified as climate finance. And on other occasions these conventional flows are cannibalized to generate climate finance. The size of the pie remains the same.

Unless we are able to increase the total amount of resources available to cater to both the development priorities and climate-friendly growth needs of emerging and developing economies, we may only be able to build a future that is both green and grim. Everywhere, low-income populations will underwrite a green future for a privileged few.

Additional finance for meaningful climate action may be generated by simultaneously working on three fronts as we move to 2020. Successful climate action will first and foremost be predicated on the domestic regulatory framework within each country. Currently, a slew of regulations, from the flow of international finance into the domestic economy to those related to debt and equity markets, disincentivize capital from investing in climate action. It is imperative for policymakers to get their own house in order and create financial market depth and instruments that allow savings to become investible capital even as they continue to demand a more climate-friendly international financial regime.

Second, there currently exists a vast pool of long-term savings—which can be labelled “lazy money”. According to a recent International Monetary Fund report, much of this lies with pension, insurance and other funds, which have accumulated savings of approximately $100 trillion. Due to lack of political will and appropriate mechanisms, this money is neither invested in the climate agreement objectives nor in the sustainable development goals agreed to at the UN last year. This helps nobody. As a result of its inability to flow across borders, developed-world savers earn sub-par returns. And due to this source of finance remaining outside the climate purview, the investment gap in infrastructure, particularly in developing countries, has continued to increase. It now stands between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion each year. Making this “lazy money” count will be extremely important.

And finally, it is time to bring the big boys controlling banking standards into the tent. The Basel III Accords, designed to create a more resilient international banking system through a suite of capital adequacy, leverage, and liquidity requirements, contribute little to global climate resilience. Given the dependency of emerging economies like India on commercial finance for capital-intensive projects, the Basel Accords need urgent review.

The infrastructure gap, global financial sustainability, and a green future are recognized to be common global problems. But the world cannot continue to solve them on three different tracks. If so, each of them will fail. Only once they are seen as inter-connected can they be addressed effectively.

Samir Saran is vice-president at the Observer Research Foundation.

India’s perspective on post-Paris climate negotiations

ORF, Expert Speak, Nov 8, 2016

Original link is here

Fletcher Forum: How do you propose an amenable bridge between global responsibilities of combatting the legacy of historic emissions from OECD countries versus controlling increases in current (and future) emissions of BRICS nations?

Samir Saran: The pre-Paris paradigm of “strict” differentiation with regards to mitigation responsibilities has now evolved into that of “universal action.”

However, the induction of the term “climate justice” still attempts to ensure the existence of a bridge between global historical responsibilities and the future emissions of developing and emerging economies. Climate justice, defined as the recognition of equitable rights to use the atmospheric global commons, is weighed in terms of mitigation and adaptation costs. Any effort to redistribute the emissions between the OECD and the global south will need to account for the cost of differential impacts caused by reduction or avoidance of emissions. In many ways, climate justice takes forward the moral arguments of the CBDR (Common But Differentiated Responsibility) and Equity debate while discarding the rigid politics that have evolved around these concepts and made agreements impossible.

That being said, there are four distinct yet overlapping future potentials of “just” climate action:

One, developed countries will have to achieve their self-designed pledges on climate finance and support for technology transfer. Greater political leadership and action from the global north will encourage developing countries to walk an extra mile in meeting their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). For instance, Indian and Brazilian NDCs have mentioned additional commitment to climate action provisional to availability of finance and technologies from the industrialised economies.

Second, a global set of rules could be developed to tax or regulate the higher emissions by corporations, institutions, and other parties across the globe, irrespective of their country’s development status. This type of normative framework must be universally agreed upon. All corporations above a certain size in certain sectors and irrespective of their geographical location must adhere to a framework of efficiency and climate awareness.

Thirdly, technology transfer from the west won’t be enough to strengthen climate action to the level that is required to limit global temperatures at two degrees or below two degrees Celsius. Indigenisation of technology innovation — both products and processes — will be critical to resolving the climate-development nexus. A more transparent knowledge sharing approach along with technology transfer will have to be put in place to support long-term climate resilience.

Fourth, “loss and damage” in the longer term must be operationalised. The Paris Agreement’s weak language regarding loss and damage, mainly the exclusion of a non-liability clause, was perhaps part of an effort to generate consensus on minimum level of commitment. Going forward, we can’t escape from setting an institutional apparatus to compensate for climate related losses that especially affect Small Island States, Least Developed Nations, and developing countries.

Global per capita emissions are negligible for India, but 13 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world are in India. What is your take on the environmental policies undertaken by some of the state governments? Do you feel there is sufficient political intent to address environmental concerns at the central level, particularly on issues like forest cover?

SS: Environmental policies alone cannot resolve India’s urbanisation challenge. There is an underlying structural and political issue, which gets veiled under the supposed “techno-managerial” clarification. A case in reference is the odd-even license plate scheme in Delhi aimed to decongest traffic and reduce air pollution. In the absence of robust infrastructure and comprehensive regulatory measures, the odd-even scheme hit a dead end. Lack of an efficient public transport system, misdirected notions of how the mega-city’s transport system should work, and the conception of the scheme itself, wherein the focus was on the number of vehicles on the road rather than the time they spent, are a few shortfalls that failed the broader intended impact of the odd-even scheme. But as I have written elsewhere, this scheme needs to be re-introduced accompanied by a slew of other measures including ‘congestion charge’, ban on diesel vehicles, rationing of vehicles per household and relooking at the notion of ‘home office’ which becomes increasingly an attractive option with communication technology and digital connectivity.

Such structural problems are mirrored by the water and waste management sector. Yamuna Action Plan I, II, and III, and the latest “Maili se Nirmal Yamuna Revitalisation” Project 2017 have endeavoured to clean one of India’s most polluted rivers. None so far have produced the desired results. This is a result of infrastructural shortcomings for waste disposal, derisory and fraudulent penalties and punishment for polluting, and growing waste generation. So we now have a situation where judicial and socio-environmental activism has maintained the pitch of the debate, but political deafness to the challenge is palpable.

How would you suggest enacting reforms in India’s overburdened and inefficient utilities or the coal sector?

SS: The Indian coal power sector is growing. In 2015–2016, coal production rose to 638 million tons (from 70 million tons in 1970s), and imports dropped by 43 percent from the previous year. The current government’s thrust on modern technologies combined with reforms in coal imports, auction, mining, extraction, and evacuation have started showing signs of sectoral improvement. However, an ambition to double coal production to 100 crores tons by 2020 will require massive improvement in the efficiency of both the product and process. Investments in research and development for clean coal technologies, improvements in boiler efficiency, and super critical technology are the lowest hanging fruits. Two aspects are critical in this sector from a climate perspective.

First, since OECD countries are neither investing in nor are mandated to develop coal technologies, the emerging economies will have to pick up the baton on research on mining technologies and boiler efficiencies. Second, every percentage gain in coal energy across the mine to power plant value chain will reduce Indian annual emissions equivalent to the entire annual emissions of some countries in Europe and elsewhere. This is a low hanging fruit that is not being bagged due to the evangelical anti-coal sentiment that is blind to its inevitable use in OECD countries and developing world.

There is much enthusiasm surrounding India’s focus on renewable energy — what lessons can India provide to other countries to develop their renewable energy sector?

SS: India’s renewable energy development trajectory presents a unique case. The country is endowed with an estimated 896 GW of renewable energy potential in the form of biomass, solar, wind, small hydro, and tidal. Besides this, the energy deficit in rural areas, increasing energy demands, and climate concerns have been the key drivers of renewable energy development in India.

To exploit this potential, India created a separate Ministry of New and Renewable Development, set national goals for biomass and solar generation, and made ambitious targets to increase the share of renewables in the total energy mix from 32 GW (2014) to 175 GW by 2022.

To provide further thrust to the sector, Prime Minister Modi along with France launched the International Solar Alliance in Paris in 2015. This group of 121 countries aim to mobilise one trillion dollars for solar investments by 2030 and improve access to solar technologies.

While it too early to present India as a successful case to learn lessons from, its vision to balance green growth along with the sovereign obligation to meet at least the lifeline energy needs of its population is an endeavour with no precedence. In a country of 400 million energy poor people, renewables offer only a fraction of a solution for energy security and economic growth. Yet, an impressive 175 GW target from renewables demonstrates the new ambition of India’s political leadership and the sense of responsibility towards global climate action. To put this ambition in perspective, India is seeking to install more renewable capacity in the next decade than the total capacity installed in Germany over multiple decades of industrialisation.

If India can pull this off, its model will be unique. India would be the first country in the world to move from a low-income society to a middle-income economy, driven significantly by renewable energy and climate conscious infrastructure. It would also be a model that is exportable to other countries similarly placed on growth ambitions and development priorities.

This interview originally appeared in The Fletcher Forum of International Affairs.

Indian climate policy in a post-Paris world

2 Feb 2016|Samir Saran and Aniruddh Mohan

Original link is here

Most experts agree that the consensus achieved at COP21 in Paris, like most global agreements, produced a sub-optimal outcome, and by itself, is unlikely to limit global average temperature rise to two degrees centigrade (much less 1.5 degrees). The real work will happen within nations, as countries begin to roll out the implementation of their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Going forward, India’s climate policy and energy policies are likely to be shaped by three documents: the Paris Agreement, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Agenda and the Indian NDC submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). All three have implications for India’s national ambitions to grow infrastructure, ensure inclusive development and maintain sustained economic growth. The agreements also raise questions around financing, namely whether the global financial architecture can respond to the needs of this new development paradigm.

India requires in excess of $1 trillion in the next five years for meeting its stated national goals. Besides the domestic mobilisation of resources, there are two fundamental challenges that need to be resolved if the country is to meet its climate and energy goals. The first is to ensure steady global funding for its traditional infrastructure and energy projects in a carbon-constrained world. That will be difficult. The World Bank has already restricted loans for building coal-fired power plants since 2013; and in November 2015, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) agreed to limit most state financing to ‘ultra-supercritical plants,’ which burn less coal to produce the same amount of electricity.

The second challenge is to reform the structural bias in the global financial architecture, which, since the global crisis, pays more attention to ‘credit adequacy’ rather than the ‘credit enhancement’ that India and other developing countries so urgently require. Aligning those banking needs and the global banking mood is an imperative for traditional, renewable and low-carbon projects.

Understanding India’s energy options is also a crucial task. On the mitigation front, the Indian NDC commits to reducing the emissions intensity of its economy by 33–35% by 2030 from 2005 levels and achieving 40% of its installed electrical capacity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. The latter commitment is conditional on receiving adequate technological and financial support. The NDC also signals that India’s per capita energy consumption may grow up to more than six times beyond 2015 levels.

As of the end of 2015, the installed capacity of clean energy sources (renewables, hydro and nuclear) in India was 30% of the total installed capacity. Therefore, even if that were to be scaled up to 40% by 2030, 60% of capacity would still be based on fossil fuels. The real room for India to maneuver is in this large block of base-load conventional generation, which will account for a majority of the actual power generation, given the low capacity factors of renewable sources of power.

According to analysis done by the Centre for Policy Research, India could have something between 600–800 GW of total electrical capacity by 2030. Taking the median figure of 700 GW, 60% of fossil fuel capacity would add up to 420 GW. The current fossil fuel capacity stands at 198 GW with 173 GW of coal and just over 24 GW gas. India is therefore likely to more than double its fossil fuel capacity by 2030, alongside the impressive commitment on increasing renewable installations.

To ensure that India’s path to development doesn’t compromise its climate action, India has a few options. First, it can ensure that the additional 200 GW of fossil fuel capacity that’s to be added up to 2030 is significantly fueled by gas. Gas-based power has roughly half the emissions of coal fired power plants. 24 GW of current gas capacity points to the limited presence of gas in India’s current energy mix and also to the potential to dramatically scale that up.

Two market conditions allow India to pursue that policy path aggressively. First, the slump in global gas prices following the restart of Japanese nuclear reactors and an oversupply in the market means that it’s the perfect time for India to negotiate new gas deals and secure long term supply at competitive prices. In fact, a lot of Indian gas plants were idle in 2015 as the prices of importing gas was more expensive than the cost of selling power. The Indian government has had to recently renegotiate the price with Qatar, its main supplier, and achieved a price reduction of about 50%. The second follows from the Iran nuclear deal, which could see Iranian gas becoming available as a viable source. Just last month, it emerged that India and Iran are considering a US$4.5 billion undersea pipeline that would connect Iran to India’s west coast via the Oman Sea. Iran has the largest gas reserves in the world and the availability of Iranian gas changes India’s energy calculus significantly.

India’s second option is to significantly scale-up nuclear power. Nuclear energy has the advantage of being both carbon free and, like gas power, available all the time. It’s therefore the only clean energy option to substitute coal in the electricity grid. However, India’s tardy rate of growth in the nuclear sector so far, with only 5.8 GW of current capacity, as well as issues with the liability law, procurement of technology and long construction times, mean that gas remains the only viable and cleaner option over the short term.

However, to make this shift to gas India needs to work on three key areas. First, the country’s gas infrastructure needs to be scaled-up so that it can link to transnational pipelines, draw from regasification terminals of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and develop last-mile connectivity to consumers.

Second and more importantly, the political will to allow for the development of an integrated gas market is needed. The difficult decision to remove direct and quasi control over pricing and end-use needs to be taken. Such a move will create conditions where benefits and costs are accrued through market operations and will help attract interest from investors, producers and distributors.

Finally, India’s geopolitical overtures need to support this new energy agenda. Financing and infrastructure development require strong global support and partnerships. India’s relationships with Iran, Qatar and Turkmenistan among others also needs to be re-energized and must be seen as part of the national imperative of seeking energy security and more robust climate action.

The tyranny of technology: time to change old systems to align with new realities

4 December 2015 4:20PM

Original link is here

In September this year, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were agreed upon by world leaders in New York and this month, countries will attempt to agree on a global deal to combat climate change in Paris. The actual success (going beyond the symbolic consensus) of both the SDGs and a potential climate agreement is contingent on technology and the extent to which it is shared, adopted and dispersed successfully.

Technology innovation, development and transfer are key to eradicating poverty, striving for equity in global lifestyles, and avoiding dangerous levels of climate change. For technology to be effectively applied to the global development and climate agenda, however, a few systemic flaws and some new realities need to be acknowledged and then responded to. A technology-centric response to the problems of the 21st century will require formulation of policies that reflect the changing nature of global technology flows, production and consumption paradigms.

The regimes of technology innovation and transfer currently in use are from a period when developed countries were both producing and consuming the products of technology innovation. This meant innovation led to increased purchasing power in the local community and the extended neighbourhood. It was therefore easier for people to absorb such innovation and pay for it. These structures are incongruous with the consumption realities of today, underpinned by globalisation. Technology innovation and production still occur in developed countries but the largest group of consumers are now in developing countries.

The scale of consumption in Asia in particular is creating new markets for corporations from the OECD countries. This trend is going to become a new reality in coming years. The McKinsey Global Institute predicts that nearly half of the economic growth between 2010 and 2025 will come from 440 cities in emerging markets. China and India will naturally lead this new consumption paradigm. And Asia will soon be joined by Africa in the shopping aisle.

Alongside these new consumers is another nuance that must be factored into the debate around technology. The largest economies of tomorrow will comprise large numbers of low income and poor households. Big economies will remain poor societies for some time to come in this century. Therefore, technology and royalty regimes around technology must cohere with development assistance paradigm and the global development agenda that seek to improve the lives of the poor.

Developed countries have provided Official Development Assistance (ODA) (defined as financial flows administered by governments towards economic development and welfare of developing countries) of about 0.29% of their own gross national products. However, what would be interesting to uncover is the amount of returns that have been repatriated to the rich economies by way of royalties that allow technology access for the developing world. For example, as per figures from the World Bank, India received US$2.4 billion in ‘net official development assistance and official aid’ in 2013. To put such figures in context, Merck, a global pharmaceutical giant, reported pre-tax profits of just under $1.6 billion in 2014. The contribution of technology royalties earned from the developing world to that figure needs to be calculated. Imagine 500 such companies which are leaders in their domain, and it is easy to see why the developmental aid flowing to parts of Asia and Africa simply does not match the scale of the money flowing out to pay for access to technology. The OECD countries, their corporations and institutions are giving with one hand and taking back with both.

A recent example of the burden of technology access are the Nokia royalty payments that flowed from India to Finland. Between 2006 and 2014, Nokia’s Indian subsidiary paid over INR 20,000 crore to its Finnish parent as royalties for the technology used in its manufacturing facility in Tamil Nadu. In 2013, Indian authorities alleged that Nokia owed over INR 2,000 crores to India on tax on the royalty payments. While this tax dispute continues, the outflow of $3 billion as royalty for handsets made by Indian factory workers — that Nokia was selling to lower and middle class Indian consumers – clearly demonstrates the profit motive of the parent is supreme.

Since royalty outflows far outweigh inflows from developmental assistance, it might make more sense for developed countries to subsidise technology diffusion in developing countries by paying their own corporations, to allow for open access to technology in developing country markets. That would perhaps deliver a better return on the money being spent by Western nations to support development in the global south, particularly given the increasing linkages between technology access and economic development.

In order to achieve the SDGs, it is also time to re-evaluate the global patents regime. For instance, Michele Boldrin and David K Levine, two economists from Washington University, St. Louis, have pointed out that the current patent/copyright system discourages inventions from actually entering the market. They opine the intellectual property rights (IPR) system only helps large corporations and multinational corporations rake up profits, noting that the majority of patents are registered by corporations rather than individual innovators. Boldrin labels intellectual property ‘intellectual monopoly’, arguing that it hinders innovation and wealth creation.

All of this does not mean that India and other developing countries do not need to look inwards and explore policies and practices for creating a culture and system that encourages innovation. The demographic dividend offers these countries a chance to develop a generation of technologists innovating for the bottom of pyramid needs. At the same time, real cooperation with the OECD countries on joint R&D will enable a blending of product innovation capabilities of the developed world and process innovation that some of the developing countries have excelled in. India’s position is that technology transfer is not enough in itself, just like Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Domestication and indigenisation of technology are prerequisites to development as well as for a non-liner growth trajectory.

Joseph Stiglitz has noted that the most defining innovations of our time were not motivated by profit but rather by the quest for knowledge. The patent system was created to reward innovators but is now stifling innovation, feeding the hunger for profits and perpetuating the north-south divide. In order to support the development agenda, combat climate change, achieve parity in global lifestyles and shape an equitable planet, the tyranny of technology must be replaced by the technology panacea.

Governmental resources and policies must be directed towards encouraging open innovation so as to avoid the incumbent’s monopoly on the current system, which is compromising the ability of developing countries to fight poverty and guarantee the right to life. There is a need for studies that examine the impact of the IPR regime on economic activity in specific sectors that will demonstrate where IPR can stimulate innovation and where it does not. The SDG and climate agendas, perhaps the defining themes of the next few decades, cannot be held hostage to the ability to pay, for a perceived entitlement to profit perversely. It is time to examine the economic distortions that have altered the founding principles of patent and intellectual property right regimes. And it is absolutely the time to re-price innovation, to deliver for the bottom of the pyramid.

A longer version of this article appeared in Global Policy and can be found here.

Photo courtesy of Flickr user World Bank

Deconstructing Indian Leadership on Climate Change

Original link is here

The Indian proposition at Paris is fairly apparent and uncomplicated; it is also ambitious and steeped in India’s reality. The proposition which is delineated in India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), can be seen to be responding to three core principles. The first foundational principle of any Indian contribution to the global effort on combatting climate change has to be to ensure that India’s wealthy – individuals, corporations and institutions — must not hide behind the country’s poor. They must bear the same level of responsibility and adhere to the same set of rules (agreed or normative) as global elites anywhere else in the world.

This can be accomplished in fairly simple ways, and certainly by taxing conspicuous consumption at many transaction points (rather that making production costlier and thereby socialising the cost of climate mitigation). This is already underway. The bulk industrial user pays comparable commercial tariff to similar users in the developed world. Indian cities have introduced consumption-based graded electricity tariffs and this principle is being, and needs to be extended to transportation fuels, gadgets and appliances and indeed to other spheres where embedded energy use tends to be socialised. Already, on an average, an Indian spends more on procuring renewable energy relative to their incomes than the average American, Chinese and Japanese. India is determined to showcase its leadership in renewable energy consumption. It is today, the world’s largest biomass, third-largest solar, and fourth-largest wind energy producer. The INDC outlines India’s ambition to significantly scale up renewable energy capacity in the country with a target to achieve 175 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022. The elite and entrepreneurial Indians form part of this first INDC proposition.

The second principle is that India does not see any fundamental incoherence between being structurally dependent on coal while also leading a global green transition. These are mutually exclusive realities and if India can get this transition right, it will have a unique model of industrialisation that can be shared with many other countries that are further down the development pathway. Coal is still a necessity for multiple lifeline initiatives of the country to lift millions out of poverty. Clean energy, on the other hand, is a transformational opportunity – a moment for India to not only assume moral leadership but to develop competitive advantage in a new paradigm for growth in a fast-changing world. The INDC document recognises that India’s electricity demand is set to increase from 774 TWh in 2012 to 2,499 TWh in 2030.

This increase is necessary if the country is to industrialise, eradicate poverty and provide its population with better living standards. This growth in energy base is predicated not only on the exponential ramp up of the clean energy generation capacity as mentioned earlier, but also through a steady and calibrated increase in its fossil fuel based generation. And as facts indicate, the unnecessary alarmism on India’s ramp-up of coal is shallow. An average Indian today burns less than 20 percent of the coal consumed by an average American or Chinese and about a third of the per capita OECD appetite1 . Further, India’s peaking per-capita emissions even after this four-fold growth in energy consumption is not likely to cross the threshold of between five to six tons per capita. In fact, based on the INDC submissions, none of the major developed nations will achieve this level of per capita emissions. The bottom line then is that, while India will “Go Green” and is seeking to lead the green transition (Solar Alliance is an example), it will also have to “Grow Coal” to meet its development objectives.

And while it is doing that, there is no reason why the veil of faux moralism that envelops the lazy European political class should prevent India from seeking efficiency gains in the coal sector. If we are to grow coal, it makes sense to do it in the cleanest way possible. 111 coal-fired power plants in India resulted in 665 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions in 2010 – 2011 from an installed capacity of 121 GW. In 2030, it is estimated that India’s coal capacity will be anywhere between 300 – 400 GW. The World Coal Association (WCA) estimates that a 1% improvement in the efficiency of a coal power plant results in reductions of 2-3% in CO2 emissions. Investment in improving efficiency of coal-fired power stations through improvements in boiler efficiency and support for purchase of super critical technology is the low hanging fruit in the climate battle. A 1% improvement over 10 years in the efficiency of just currently operating coal power plants in India will save the entire current emissions of Belgium. A 1% improvement in future coal capacity will save the entire current emissions of Australia2 . At the same time, the irrational alarmists residing within India and in the developed world must note that despite the necessary growth of coal, India’s emission will peak lower than any other country that would have industrialised before it and its transition time will be much quicker.

Finally, India, due to its diverse agro-climatic regions, is already experiencing the negative impacts of climate change and extreme weather conditions. It will need to create innovative social policies and business models that are able to increase the resilience of local communities and help fund and strengthen the nation’s adaptive capacities to climate change. Any development policy implemented today must always be to increase the ability of the poor and weak to respond to climate change. Despite the adverse impact climate change will have on sectors such as agriculture and coastal economies, the Indian government recognises that assistance from the developed world on climate change adaptation will not be forthcoming. Taking this into consideration, the Government of India has indicated its intention to set up its own domestic adaptation fund in its INDC. If global partnerships contribute in this effort, vital resources can then be diverted to further bolster mitigation actions.

Having outlined the Indian proposition, let me now define three structural infirmities in the global system that must be resolved if collective action on climate change is to be successful. The first stems from the tyranny of incumbency. Carbon space capture by incumbents has created limited room for the development needs of those who require this space to breathe and grow. Therefore, before carbon space or resource space can be retrieved, the discursive space needs to be reclaimed for a sensible conversation on climate change. The discourse needs to change from the unavailability of carbon space in light of climate realities to one where carbon space is vacated by developed countries so as to accommodate the needs of developing nations. For every new coal plant that comes up in India, one in the West should be shut down. The early raiders of the 19th and 20th century got away with the carbon loot but it’s time that carbon space is reclaimed. When a shift from unavailability to accommodation takes place and when incumbents within and across nations are encouraged and compelled to cede space, we will find that there is new room to manoeuvre.