original link is here

Monthly Archives: August 2017

Privacy Inc.: The one where Supreme Court saved Aadhaar

Samir Saran

The Supreme Court’s recent 547-page verdict affirming the fundamental right to privacy of Indians should not come as news to technology companies. The court merely codifies what should have been an article of faith for internet platforms and businesses: the user’s space is private, into which companies, governments or non-state actors must first knock to enter.

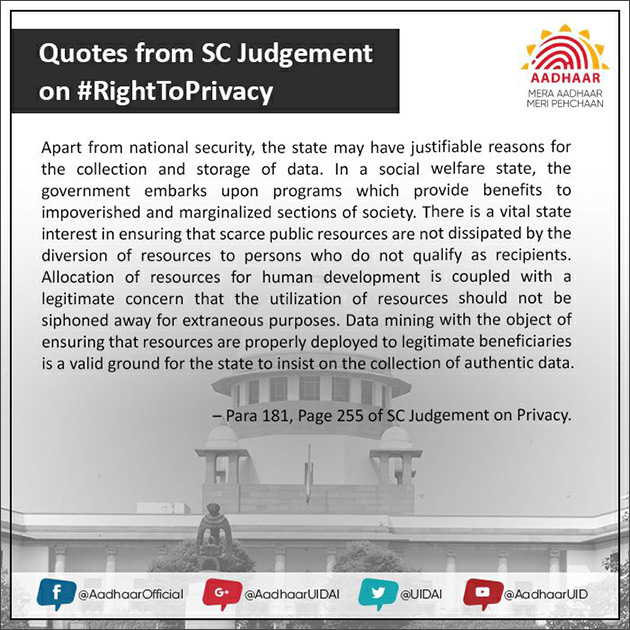

The technical architecture of Aadhaar and its associated ecosystem too will now be tested before a legal standard determined by the court, but the government should see this judgment for what it is – a silver lining.

The verdict bears enough hints to suggest the Supreme Court sees the merits in a biometrics-driven authentication platform. In fact, Justice Chandrachud impresses upon the possibility of better governance through big data, highlighting that it could encourage ‘innovation and the spread of knowledge’, and prevent ‘the dissipation of social welfare benefits.’

The court’s words should spur the government to create a “privacy-compliant Aadhaar”, but this requires a serious and systematic thinking on the part of its visionaries and architects. Private sector too will have to put “data integrity” and privacy at the core of their consumer offerings and engagement.

To begin with, the government must account for Aadhaar’s biggest shortcomings — its centralised design and proliferating linkages.

A central data base creates a single, and often irreversible, point of failure. The government must decentralize the Aadhaar database. Second, Aadhaar must be a permission-based system with the freedom to opt-in or out, not just from the UID database but from the many services linked to it. This must be a transparent, accessible and user friendly process.

With a “privacy-compliant” Aadhaar, the government would not merely be adhering to the Supreme Court verdict. It would also be on the verge of offering the world’s most unique governance ecosystem, a feat that more technologically advanced nations such as America and China have failed to achieve.

Take Beijing’s efforts in this space, for instance. In 2015, the government of the People’s Republic of China unveiled a national project to digitize its large, manufacturing-intensive economy and to create a digital society. The “Internet plus” initiative, as it was called, aimed for the complete “informationisation” of social and economic activity, and harvest the data collected to better provide public and private services to citizens. China has no dearth of capital or ICT infrastructure, but the ‘Internet plus” initiative has struggled to take off in any significant way, nor has it found any international takers. The project suffered from a fundamental flaw: Beijing believed by gathering information — from personally identifiable data to more complex patterns of user behaviour — the state would emerge as the arbiter of future economic growth, consumption patterns and indeed, social or political agendas.

But trust in the digital ecosystem, as the failed Chinese government attempt at technology enabled social-engineering shows, can only be built by addressing those needs which extend to the demand for freer expression, political dialogue and economic mobility. On account of its closed governance model, Beijing has arguably failed to generate such trust among internet users. China’s failure to move forward on its grand digital project bears lessons for India.

If a project like Aadhaar is to succeed, its underlying philosophy must be premised on two goals: first, to increase trust and confidence in India’s digital economy among its booming constituency of internet users, and second, to ensure that innovations in digital platforms also result in increased access to economic and employment opportunities.

A privacy compliant Aadhaar creates trust between the individual and the state, allowing the government to redefine its approach to delivering public services. The Aadhaar interface, that UPI and other innovations rely on, could well generate a ‘polysemic’ model of social security, where the same suite of applications cater to multiple needs such as digital authentication, cashless transfers, financial inclusion through a Universal Basic Income, skills development and health insurance. But such governance models should not be based on a relationship of coercion or compulsion. It is heartening that the country’s political class has embraced the court verdict, with BJP’s leaders like Amit Shah affirming their commitment to create a “robust privacy architecture” and the Srikrishna Committee’s efforts to recommend one.

A key reform missing in current debates about the UID platform is the government’s accountability for its management. Aadhaar, to this end, should have a chief privacy officer — or indeed a “privacy ethicist” not unlike the major technology companies —who will be able to assess complaints, audit and investigate potential breaches of privacy with robust autonomy.

An Aadhaar based ecosystem which is both privacy-compliant and has built a bottom-of-the-pyramid financial architecture would inspire confidence in other emerging markets to also adopt the platform, with Indian assistance.

Companies and platforms must internalise that promise of black box commitments towards privacy and data-integrity may no longer suffice. These commitments must be articulated at the level of the board and communicated to each user that engages with them. Overseers of data integrity must be appointed to engage with users and regulators in major localities.

India’s digital growth story must be scripted by its people and for its people. The Indian state, however, has an important role to play here — it should catalyse technology platforms that provide reliable, affordable and qualitative internet access to citizens. But most importantly, the state should articulate a bold political, legal, and a philosophical narrative that can drive innovations, both by public and private organizations, in India and abroad. With a privacy compliant Aadhaar, this narrative could be one of empowerment, inclusivity and prosperity enabled by digital networks.

(A shorter version of this article was published in Economic Times)

Opportunity knocks, Aadhaar enters

Economic Times, August 29, 2017

Original link is here

The Supreme Court’s verdict affirming the fundamental right to privacy should not come as news to technology companies. The court merely codifies what should have been an article of faith for Internet platforms and businesses: the user’s space is private, into which companies, governments or non-state actors must first knock to enter.

The technical architecture of Aadhaar and its associated ecosystem, too, will now be tested before a legal standard determined by the court. But GoI should see this judgment for what it is: a silver lining. The verdict bears enough hints to suggest the court sees the merits in a biometrics-driven authentication platform.

In fact, Justice DY Chandrachud impresses upon the possibility of better governance through big data, highlighting that it could encourage “innovation and the spread of knowledge”, and prevent “the dissipation of social welfare benefits”. The court’s words should spur GoI to create a ‘privacy-compliant Aadhaar’.

But this requires systematic thinking on the part of its architects. The private sector, too, will have to put ‘data integrity’ and privacy at the core of their consumer offerings and engagement.

For starters, GoI must account for Aadhaar’s biggest shortcomings — its centralised design and proliferating linkages. A central data base creates a single, and often irreversible, point of failure. GoI must decentralise the Aadhaar database.

Second, Aadhaar must be a permission-based system with the freedom to opt-in or out, not just from the (unique identification (UID) database but from the many services linked to it. This must be a transparent, accessible and user-friendly process.

With a ‘privacy-compliant’ Aadhaar, GoI would not merely be adhering to the Supreme Court verdict, but also be on the verge of offering the world’s most unique governance ecosystem. Take Beijing’s efforts, for instance.

In 2015, the Chinese government unveiled a national project to digitise its large, manufacturing-intensive economy and to create a digital society. The ‘Internet-plus’ initiative aimed for the complete ‘informationisation’ of social and economic activity, and harvest the data collected to better provide public and private services to citizens.

China has no dearth of capital or ICT infrastructure. But the ‘Internet plus’ initiative has struggled to take off in any significant way. The project suffered from a fundamental flaw: Beijing believed by gathering information — from personally identifiable data to more complex patterns of user behaviour — the State would emerge as the arbiter of future economic growth, consumption patterns and, indeed, social or political agendas.

If a project like Aadhaar is to succeed, its underlying philosophy must be premised on two goals: first, to increase trust and confidence in India’s digital economy among its booming constituency of Internet users; and second, to ensure that innovations in digital platforms also result in increased access to economic and employment opportunities.

A privacy-compliant Aadhaar creates trust between the individual and the State, allowing the government to redefine its approach to delivering public services. The Aadhaar interface, that the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and other innovations rely on, could well generate a ‘polysemic’ model of social security, where the same suite of applications cater to multiple needs such as digital authentication, cashless transfers, financial inclusion through a Universal Basic Income, skills development and health insurance.

But such governance models should not be based on a relationship of coercion or compulsion. It is heartening that India’s political class has embraced the court verdict.

A key reform missing in current debates about the UID platform is GoI’s accountability for its management. Aadhaar, to this end, should have a chief privacy officer who will be able to assess complaints, audit and investigate potential breaches of privacy with robust autonomy.

A privacy-compliant Aadhaar, with a bottom-of-the-pyramid financial architecture, would inspire confidence in other emerging markets to also adopt the platform, with Indian assistance. Companies and platforms must internalise that promise of black box commitments towards privacy and data-integrity may no longer suffice. These commitments must be articulated at the level of the board, and communicated to each user that engages with them. Overseers of data integrity must be appointed to engage with users and regulators in major localities.

The writer is Commissioner, Global Commission on the Stability of cyberspace

How India and the US can lead in the Indo-Pacific

the interpreter, Friday, August 18, 2017

Original link is here

Although the Pacific and Indian Oceans have traditionally been viewed as separate bodies of water, India and the US increasingly understand them as part of a single contiguous zone. The US Maritime Strategy (2015), for example, labels the region the ‘Indo-Asia-Pacific’, while Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Donald Trump referred to it in their recent joint statement as the ‘Indo-Pacific.’

India and the US have a strong stake in seeing this unified vision become a reality. It would increase the possibility that they could promote liberal norms and structures such as free markets, rule of law, open access to commons, and deliberative dispute resolution not just piecemeal across the oceans, but rather in a single institutional web from Hollywood to Bollywood and beyond. Given the region’s economic and demographic dynamism and the importance of its sea lanes to global trade and energy flows, the significance of such a liberal outcome cannot be overstated.

India and the US have publicly called Indo-US cooperation the lynchpin of their strategy in the region. But it has not been as productive as it could be. Robust maritime cooperation between the two countries began only after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which demonstrated the increasing capabilities of the Indian Navy. Even since then, however, India has generally not been a proactive partner, and in fact often has refused US offers of cooperation. In some cases it appears to have done so out of concern for Chinese sensibilities. For instance, a senior Indian official recently suggested that New Delhi had rejected numerous US Navy requests to dock ships at the Andaman Islands in part because of China’s ‘displeasure’ about the US presence in the Indian Ocean.

The US, for its part, has repudiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership, once touted as the economic bedrock of its Asia strategy, and is distracted by Russian machinations in Europe and the Middle East, and the continuing war in Afghanistan. In addition, bureaucratic divisions between US Central and Pacific Commands hamper Indo-US cooperation west of the Indo-Pakistan border, where the US-Pakistan relationship dominates.

China has taken the real initiative in constructing a wider Indo-Asia-Pacific region. Its strategy is multi-faceted. China erodes the autonomous politics of sub-regional groupings, using its economic leverage to create differences amongst ASEAN members, denying strategic space to India through economic projects like the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, and using North Korea to limit Japanese and US influence in East Asia. China also employs institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, construction and finance projects linked to the Belt and Road Initiative, and trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership to create a network of physical infrastructure and strategic dependence across the region. This network includes ports in Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Pakistan; oil and gas projects off the coast of Myanmar; and a military base in Djibouti.

China’s strategy will increasingly put it in a position to create institutions, generate norms, and make and enforce rules in a zone stretching from East Asia to East Africa. Although Chinese preferences are uncertain, it seems unlikely that such a Sino-centric model will adhere to the liberal norms and practices that the US and India hope will take root in the Indo-Asia-Pacific. Indeed, Chinese behaviour, which includes territorial reclamations, rejection of maritime-dispute arbitration, establishment of an air-defence identification zone, and confrontations such as the ongoing Sino-Indian standoff over borders in Bhutan, suggest an authoritarian approach to the region.

Recognition of these dangers has been a central driver of US-India strategic cooperation. If the US-India partnership is to confront them effectively, however, the two countries must think more creatively about how better to work together, particularly in the defence sphere.

The core elements of Indo-US defence partnership include movement toward the adoption of common platforms and weapons systems as well as shared software and electronic ecosystems; closer cooperation on personnel training; and the convergence of strategic postures and doctrines. These elements can realise their full potential only if the two countries enable large-scale US-India data sharing, which will significantly enhance interoperability between their two militaries. This, in turn, will be possible only through the signature of the so-called Foundational Agreements, which provide a legal structure for logistical cooperation and the transfer of communications-security equipment and geospatial data.

India has historically resisted signing these agreements. But many Indian objections are rooted in domestic political calculations rather than substantive strategic concerns. Moreover, with the 2016 signature of the logistics agreement known as LEMOA, India may have crossed an initial hurdle. Perhaps a concerted effort to reconsider objectionable language, without fundamentally altering their substance, could make the remaining agreements palatable to Indian leaders. Given the impact this would have on India’s ability to cooperate with the US to meet the Chinese challenge, it could get serious consideration in New Delhi.

India and the US can take a page from China’s military strategy. Much has been made of the dangers of China’s anti-access/area denial capabilities. But India can also leverage its geography to impede access to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. For example, with US assistance, it could transform the Andaman and Nicobar islands into a forward-deployed base for surveillance and area-denial assets. This would exploit natural Indian advantages, hamper China’s ability to expand its reach and consolidate its gains across the region, and not require India to shoulder unrealistic burdens in far-off areas of operation.

India and the US also need to take a diplomatic and developmental approach to the region that is geographically holistic and offers credible alternatives to Chinese projects; they should not adopt disparate strategies east and west of the Indian Ocean, or promote projects that are rhetorically attractive but lack financial and diplomatic ballast. Recent announcements of pan-regional projects such as the Indo-Japanese Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, and the revived US Indo-Pacific Economic Corridor and New Silk Road initiative, are welcome developments. It will be essential to ensure that these projects continue to receive adequate support, and to create synergies between them that can help to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Additionally, India must cultivate political relationships in its close neighborhood with countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, the Maldives and the ASEAN members to project its influence into the Indian Ocean. Regional states have already begun to fall prey to China’s ‘debt trap’ diplomacy. For instance, Sri Lanka has struggled to service its debt owed to China for the construction of the US$1 billion Hambantota port, which has put the government in Colombo under considerable political and economic duress. India should offer its neighbors sustainable infrastructure projects and strong economic incentives that can provide an alternative. These efforts will be more likely to succeed if the US, Japan and Australia support them diplomatically and through co-investment in economic ventures.

None of these measures will be easy to implement; they will face resource constraints, political opposition, and strategic competition. But the stakes – who gets to construct the legal, economic, and military architecture of an integrated Indo-Pacific region – are enormous. Without bold policy from the US and India, the answer will be China.

There’s a standoff between China and India in the Himalayas. Both sides explain

A dispute high in the Himalayas threatens years of diplomatic progress

Original link is here

Indian and Chinese forces are locked in a stand-off high in the Himalayas, where the borders of India, China and Bhutan come together. In recent years, observers have grown used to such disputes being worked out peacefully, with a mutual face-saving solution. But as time goes by, concerns that this incident could mark the beginning of a longer term downward trend in Sino-Indian relations are rising.

To help understand the origins, significance and potential resolution of the Doklam stand-off, we asked Professor Wang Dong from Peking University, and Doctor Samir Saran, the Vice President of India`s Observer Research Foundation, to present their perspectives on these questions.

What is the origin of this dispute?

Wang Dong: On 16th June, 2017, the Chinese side was building a border road in Dong Lang (or Doklam), which is close to the tri-junction between China, Bhutan and India, but belongs to Chinese territory.

On 18th June, 2017, Indian border troops, in an attempt to interrupt China’s normal road construction, illegally crossed the demarcated and mutually recognized Sikkim section of the border into Chinese territory, triggering a standoff that has thus far seen no ending. In the past, border standoffs between China and Indian all occurred in disputed areas. This time, however, the standoff took place along a demarcated borderline which has been established by the 1890 Convention between Great Britain and China Relating to Sikkim and Tibetand has been accepted by successive Indian governments since independence in 1947. Given that the Doklam Plateau is located on the Chinese side, as accurately stipulated in the Convention, and that the Doklam area has been under China’s continuous and effective jurisdiction, it is crystal clear that the Doklam standoff is caused by Indian border troops illegally trespassing into Chinese territory. Indian border troops’ illegal intrusion into Chinese territory has not only unilaterally changed the status quo of the boundary, but also gravely undermined the peace and stability of the China-Indian border area.

There is no legal basis in India’s claim that New Delhi acts to assist Bhutan in defending its territory. Nothing in the Friendship Treaty between Bhutan and India justifies India’s cross-border intervention. India’s incursion into Chinese territory under the excuse of protecting Bhutan’s interests has not only violated China’s sovereignty but also infringed upon Bhutan’s sovereignty and independence. It should be noted that in fact it is pressure and obstruction from India that prevented Bhutan from concluding a border agreement with China and thus completing negotiations of establishing a diplomatic relationship between China and Bhutan. The bottom-line is that India has no right to hinder boundary talks between China and Bhutan, much less the right to advance territorial claims on Bhutan’s behalf. Indeed, India’s behavior will set a very bad example in international relations. Does New Delhi’s position suggest that China also has the right to intervene on behalf of another country which has territorial dispute with India?

Also, India has cited “security concerns” of China’s road building as a justification of its illegal incursion into Chinese territory, a position that runs counter to basic principles of international law and norms governing international relations. Given the fact that India has over the years built a large number of infrastructure facilities including fortifications and other military installations in the Sikkim section of the border area (that actually dwarves the very little infrastructure China has built on its side of the boundary) that poses a grave security threat to China, does India’s stance imply that China could also cite “security concerns” and send its border troops into India’s boundary to block the latter’s infrastructure buildup?

As Confucius says, “Do not do unto others what you do not wish others to do unto you.” New Delhi should heed the sage’s wisdom.

Samir Saran: The dispute was triggered by China’s construction activities on the Doklam plateau, which is at the tri-junction of Bhutan, India and China. India and Bhutan both acknowledge Doklam as a tri-junction and, as such, the boundary points of all three countries around it should be settled through consultations. In fact, the India-China Special Representatives dialogue agreed to do precisely this in 2012. China’s military activity seeks to change facts on the ground, rendering any diplomatic or political boundary negotiation moot. Now, China may unilaterally assert where the tri-junction actually lies, but in an age where maps are drawn, scrutinised and contested on social media, it behoves Beijing to adopt a statesmanlike approach to this dispute.

India sought to prevent China from pursuing such construction on the Doklam plateau for two reasons: first, in keeping with the India-Bhutan Friendship Treaty, India coordinated with Bhutan on all matters, including security issues, of mutual interest. India is acutely conscious of the fact that it is the net security provider in South Asia, and that military activities cannot but, be conducted through mutual consultations, no matter how big or small your neighbour is. One wishes the leadership in Beijing too embraced this principle. By asking China to desist from unilateral activity in Doklam, India sought to reassure its smaller neighbor that it will not allow Beijing to unilaterally change the boundary situation to Bhutan’s detriment. Second, the military implications of China’s infrastructure activity in the region, located close to the narrow Siliguri corridor which connects mainland India to its north eastern states, are worrisome for India. By intervening, India is making it clear that it will act forcefully to protect not only its territorial claims but also its sovereignty and national security interests.

On a more strategic assessment, this dispute is perhaps a harbinger of the Himalayan fault-line that is bound to get sharper as India’s economy grows and China continues to seek greater political and normative influence in the sub-continent. China must internalize that a multi-polar world will also necessarily see a multi-polar Asia emerge and its attempt to become the sole determinant of political outcomes in the region may be challenged.

What issues are shaping perceptions about the wider meaning of this stand-off?

Samir Saran: There is little doubt that the border dispute is the byproduct of a larger rivalry between China and India, both of whom can decisively steer the future of Asia. New Delhi is wary of China’s ambition to “hard-wire” its influence in the region through infrastructure and connectivity projects in order to emerge as the sole continental power. Already, India-China ties have deteriorated as a result of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor – which passes through the disputed Pakistan occupied Kashmir – seen by India as a clear affront to its sovereignty.

A unipolar Asia does not serve India’s interests. Accordingly, India is determined to be a reliable partner to its South Asian and other regional interlocutors. New Delhi realizes it must leverage its fast growing economy and military capacities to offer trade partnerships and security arrangements to other countries on the continent. By coming to Bhutan’s assistance on this border, New Delhi is making it clear the dispute will not be resolved without accounting for Bhutan’s interests. The subtext of the most recent iteration of the Malabar naval exercises, which sees participation from the US and Japan (and possibly Australia in the future), was a signal to China that unilateral militarization, such as the kind China engaged with in the South China Sea, will not be acquiesced to.

India understands the importance of being able to resolve bilateral disputes with China in a peaceful manner. We are the two biggest countries in Asia —with land and maritime borders extending in all directions — and how both countries manage their differences will determine the region’s stability. New Delhi has steadfastly abided by a rule based international order, often against its own interests. In 2014, for example, India accepted an adverse arbitral ruling regarding an UNCLOS dispute with Bangladesh. In comparison, China has run roughshod over its neighbours in the South China Sea, going so far as to threaten war with them. By highlighting the need to peacefully resolve the current border dispute, India is telling China, “Look, we have a problem here. For our sake and the region’s, we should adopt a mature and sensible attitude towards its resolution”.

Wang Dong: The root causes of the standoff in Doklam are multiple. First of all, since Narendra Modi took office as Prime Minister of India in May 2014, India has gradually shifted away from its traditional non-alignment policy, and moved closer to the United States and its allies such as Japan and Australia. Many Indian officials and analysts believe that Beijing has been taking the side of Pakistan in the ongoing India-Pakistan conflict. They also regard China as a stumbling block to India’s efforts to join the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). Second, India’s misperception may also come from the fact that India has always been highly sensitive, sometimes even paranoid, about infrastructure projects initiated by China in border regions, whereas it has failed to account for its own much more intensive military infrastructure buildup along the border area.

While the “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” has become the flagship project of China’s much touted “Belt and Road Initiative”, India views it as a part of the “New String of Pearls” strategy attempting to besiege India. Third, India’s swelling nationalism in recent years, exacerbated by a deepening threat perception against China, may have misguided its policy deliberations. After the standoff in Doklam occurred, a senior Indian military leader claimed that ”India is no longer the India of 1962”—an indication that India has not completely come out from its psychological shadow as a victim in the 1962 Sino-Indian border conflict. Indian leaders should resist the temptation to play up its domestic nationalism, and avoid making wrong decisions that will have a severely negative impact on the Doklam logjam as well as the future of Sino-Indian relations.

Despite repeated urging and warning from the Chinese side, India so far has refused to fully withdraw its border troops. If India continues to refuse to do so, it is likely to lead to the worst case scenario: the outbreak of an armed conflict between the two countries. However, this will be a heavy blow to the diplomatic achievements made by the two countries over the past 30 years.

Moreover, India will also have to pay a heavy price for its diplomatic blunder. Since the Bharatiya Janata Party took the power in 2014, domestic Hindu nationalism has been on the rise. If New Delhi fails to gain an upper hand should a military conflict break out, the ethnic and religious tensions in India are likely to be intensified, causing domestic upheaval and imperiling the political status of the BJP. Enormous demands for domestic infrastructure development in India may also be delayed, and ultimately India may miss the opportunity for economic development. On the other hand, even if China prevails in a military conflict, China’s relationship with India will suffer. The conflict will also likely create enduring enmity between New Delhi and Beijing, lock the two major powers into a lasting geostrategic rivalry, and inflict great damage to important pillars of a multipolar world such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the BRICS, and Group of 20 (G20). Therefore, it is necessary for China and India, the two most important developing countries in the world, to solve the Doklam standoff peacefully, avoid sending bilateral relations into a downward spiral, and maintain regional peace and stability.

What are the chances of it getting out of control?

Samir Saran: India acknowledges the importance of a diplomatic resolution, but is also wary of being perceived as indecisive or incapable of standing up to Chinese aggression. It is aware that the reputational costs of ceding to Beijing (or being seen as such) will be just as damaging as any loss of territory. Rhetoric from New Delhi has been strong. Reports also suggest the Indian military has reinforced its positions in the area’s surrounding the disputed region.

The Indian government has demonstrably been more sober about the dispute than Beijing. So it is unlikely that India will seek to escalate the conflict. On the other hand, New Delhi is just as unlikely to withdraw unilaterally and, to this end, may be willing to continue standing up to China were tensions to escalate.

Wang Dong: At present, the nature of the Doklam standoff is abundantly clear: it is caused by the illegal incursion into China’s territory by Indian border troops to obstruct China’s normal road construction. Thus, the top priority is for India to withdraw its troops back to its own boundary. Although China has the will to resolve the Doklam standoff peacefully and has so far exercised maximal restraint, the Chinese government has made it clear that it is determined to steadfastly safeguard China’s sovereignty “whatever the cost”, should India refuse to withdraw troops and thus peacefully resolve the standoff.

What should be highlighted is that China does not wish the Doklam standoff to get out of control, and it will endeavor to peacefully resolve the standoff. Nevertheless, the root cause of the standoff is India’s illegally trespassing the border into Chinese territory, so the initiative to resolve the deadlock lies in the hands of India.

How can the parties de-escalate the situation?

Samir Saran: Neither India nor China can afford to ignore the geopolitical implications of their actions. If the contest is to be resolved, the situation at Doklam must be de-escalated through the mutual withdrawal of troops, followed by a summit level conversation between the two countries. While a National Security Advisor level meeting amongst the BRICS countries has already taken place in July, possibly opening up space for a dialogue, the importance of the issue implies that it will have to be taken up at the leadership level. This is probably a good time to reinvigorate the Special Representatives dialogue process on boundary settlement. Both sides will have to dial down the rhetoric and more importantly, offer face saving concessions in order to placate domestic sentiments and larger strategic anxiety. This face-off is also a reminder of the need for both countries to create new constituencies, from among industry, think tank/ academia and civil society more broadly, that seek a stronger bilateral relationship.

Wang Dong: China and India will both benefit from cooperation, or get hurt from confrontation. China consistently holds a clear stance on the Doklam standoff that the precondition and basis for any dialogue between the two sides would be India’s withdrawal of its border troops first. In recent weeks, India seems to indicate its willingness to solve the deadlock through diplomacy and negotiations. Indian National Security Adviser Ajit Doval has just attended the BRICS NSA meeting in Beijing, and has met with both President Xi Jinping and State Councilor Yang Jiechi.

The longer the standoff lasts, the worse the damage it would inflict on bilateral relations between the two countries. Now the ball is in the court of India. New Delhi should take responsible measures to correct its wrongdoing and de-escalate tensions. Provided that India withdraws its personnel that have illegally crossed the border and entered into Chinese territory that will set the stage for both sides to find a diplomatic solution to the standoff. Apart from negotiations at government level, public diplomacy including dialogues between think tanks and could also help to break the tit-for-tat logjam and send out signals to each other for further reducing tensions and settling the dispute. In a sense, the standoff is a symptom of the deepening security dilemma between China and India in recent years. In the long run, both sides need to exercise political will and wisdom to correctly gauge each other’s strategic intentions, reverse the worsening security dilemma, and chart a positive-sum trajectory of China-India relations that will greatly contribute to a stable and prosperous multipolar world.