Category Archives: Sustainable Development

Rethinking climate governance

New approaches should reduce the cost of capital, bridge the technology divide and develop new pathways to cooperation.

Climate change is the most salient example of a challenge that demands global cooperation to solve. Yet, this necessity has so far failed to translate into a cooperative mechanism that can withstand geopolitical shocks, partly because trust in the current approach is eroding.

The challenge: global frameworks haven’t kept emissions from rising

In 2023, the world breached the critical 1.5°C average temperature rise barrier for the first time. It is now visibly evident that the impacts of human activity on the climate are no longer a thing of the future. Climate-induced natural hazards are now among the foremost threats to lives and livelihoods, as witnessed by the devastating floods in Libya, East Africa, Italy, Yemen and Pakistan in 2023 alone. The Global South is particularly vulnerable, with some estimates suggesting that the gap in economic output between the world’s richest and poorest countries could be as high as 25 per cent compared to a world without climate change. The future looks even bleaker, with predictions from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggesting that if current emission pathways are maintained, average temperatures could rise 3.2°C by 2100.

Yet the global climate governance framework has failed to deliver. Despite various landmark agreements in Rio (1992), Kyoto (1997) and finally Paris (2015), emissions have continued to rise. Trust has broken down between developed and developing countries, given that the former have not only refused to make binding commitments on emission reduction, but have also failed to deliver on whatever meagre promises they did make – for example, to provide $100 billion annually to the developing world by 2020.

However, the fact is such tussles distract from the real scale of the problem. The final text at COP27 noted that between $4 and $6 trillion needed to be invested annually in renewables and decarbonisation solutions if the world was to stay on track to its Paris commitments. Even less ambitious targets, such as the 2022 Report of the High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, noted that annual investments would have to be between $2 and $3 trillion annually, with at least $1 trillion of that being foreign private investment. Instead of identifying solutions to raise and target flows of this scale, global governance has lost its way fighting over small, insignificant change.

The $100 billion figure has been left behind by events. It is now necessary to think in trillions. For that to happen, the debate needs to be reframed away from questions of guilt and compensation and towards obligation and opportunity. Fortunately, restructuring climate investment as an opportunity is entirely possible given that the technologies to combat climate change are becoming increasingly cost-effective: The IPCC estimates that the global average cost of renewable energy has dropped by up to 85 per cent since 2010. As a consequence, over 80 per cent of climate projects in the developed world are financed by the private sector, which sees a clear business case for green investment in those geographies.

However, investment in the Global North alone will not address a global problem. Only around 25 per cent of global climate finance currently flows to the Global South, although the developing world is where vast new investments in infrastructure and energy access are actually needed. The prohibitive cost of capital in the emerging world means that, in contrast to the developed world, only 14 per cent of green investment originates from private savings.

A new approach for rethinking climate governance

The differentials in the cost of capital between the Global North and South are prohibitive and the largest constraint on private investment flowing into climate action where it is most needed.

There is now a need to rethink global climate governance. The fundamental imbalance is this: While the developed world has been the key contributor to historical emissions, future emissions will be concentrated in the developing world. For instance, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates one-quarter of global energy demand growth between 2019 and 2040 might come from India alone. This energy growth is natural if crippling energy poverty in countries like India is to be addressed. The advantage for policymakers is that much of the energy infrastructure in these countries is yet to be built, and there is an opportunity for new, greener development that does not mimic carbon-intensive pathways adopted by the developed world. Development is energy-intensive, but it does not have to be carbon-emitting.

It is necessary to not just increase the amount of private capital deployed in the Global South, but also to ensure the scope of such investment is widened to include adaptation. Scaling up private investment into renewable energy, particularly grid-scale solar power, is easy to at least imagine. Yet other use cases for climate capital are no less important and need to be financialised. Traditional water conservation methods, regenerative agriculture, drought-resistant practices and seeds, low-cost community infrastructure like bunds to protect against sea level rise and salination – all these can no longer be financed out of public finances alone and must be seen as priority targets for private capital. Finally, the technology needed to scale up green energy solutions also remains concentrated in the developed world and China, requiring the Global South to often pay a heavy premium for using these technologies. Resolving these inequities and addressing the geopolitics around those imbalances will be imperative for achieving the Paris targets and necessitate a radical re-imaging of global cooperation around climate action.

Fortunately, climate action aligns well with the national development strategies of much of the emerging world. The Indian G20 Presidency highlighted the need to place green development at the heart of the climate action agenda. For the global energy transition to be successful, the right conditions need to be created for the Global South to use this transition as a means to eliminate energy poverty, create new economic opportunities and resolve existing gender and health inequalities. The outcome from COP28 in Dubai has kindled renewed hope for multilateral climate cooperation. For the first time there is a clear consensus on the need to transition away from all forms of fossil fuels. The operationalisation of the loss and damage fund and the decision on the global adaptation goal also sends a strong message that adapting to the impacts of climate change is now just as important as mitigation. Yet, the decisions from COP28 fall short of outlining a clear pathway for providing the means of implementation necessary for effective climate action in the Global South. Going forward, ambition must be combined with equity if the United Arab Emirates consensus is to be implemented.

The following are proposals to reimagine global climate governance:

Reduce the cost of capital: The global financial architecture needs urgent reform and re-targeting. Much climate investment requires capital upfront, with savings paying out over long tenures, sometimes in decades. The differentials in the cost of capital between the Global North and South are prohibitive and the largest constraint on private investment flowing into climate action where it is most needed. Ending this problem will need a vast expansion of guarantees and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA)-like schemes.

Traditional reasons for this spread in capital costs are related to the political risks of investing in developing countries. Sovereign risk is, of course, real, but it is also often exaggerated. Certainly, reducing the spread of sovereign risk is a vital task for international financial reform. Climate risk is the greatest threat to the stability of the international financial system. Sovereign risk cannot be allowed to outweigh climate risk.

Bold new initiatives are needed to address the question of sovereign risk delaying climate action. For example, it may be necessary to produce internationally administered pools of capital that directly discount the cost of capital for projects and platforms related to climate action.

India’s experience with digital public infrastructure has shown that there are other possible approaches. The creation of global public goods need not be cost-intensive. A global pipeline of 10,000 climate projects, each with a clear timeline, risk-reward payoff, and carbon scoring – which together might mitigate a significant proportion of future emissions – would represent such a global public good. A green infrastructure database on such a scale would allow for the much faster and more transparent mobility of green capital.

Thus, the mandate and lending patterns of multilateral development banks (MDBs) must be changed if they are to tackle the climate change. These entities can be instrumental in channelling greater financial flows to the Global South by taking on some of the risks that prevent private capital flows to these geographies. While the key areas for reform have been identified by several independent committees, there is a need for clear, time-bound action. An independent committee under the Indian G20 Presidency has put forward a roadmap for MDB reform, aiming to make the provision of global public goods a pivotal mandate alongside existing priorities. This roadmap must be made more ambitious, along the lines suggested above.

Bridge the technology divide: The lesson of the pandemic for the developing world was that even lifesaving technology in a health emergency may not flow quickly enough between the Global North and the Global South. It is natural, therefore, to ask how technological diffusion will work in the climate space.

The global understanding of intellectual property in the health sector is that patent protection is vital for innovation but also that, on occasion, governments may have the duty to override protections in the face of emergencies. The right to issue compulsory licences is rarely invoked but is a vital part of the international property rights landscape. A similar mechanism needs to be deliberated on for climate tech. The presence of the possibility of compulsory licenses also ensures that many companies have the incentive to be good global citizens and provide voluntary licences that spread access to lifesaving technology while preserving a satisfactory share of their profits. Regulators and global institutions need to be able to create a parallel set of incentives for climate tech.

Fortunately, emerging economies are also seeing the emergence of a home-grown cleantech ecosystem driven by start-ups looking to disrupt traditional energy systems. This innovative sector might solve the problem of scaling up climate tech, but home-grown innovation continues to suffer from a lack of available public funds to incentivise research, reduced access to cutting-edge tech and a shortage of early-stage risk capital to bring certain technologies to commercial scale. Creating the right mechanisms to connect available risk capital in the Global North to cleantech ecosystems in the emerging world will be essential to bridging this innovation gap. Voluntary licensing can play a role in this mechanism as well.

Repositioning the start-up sector in the emerging world towards climate goals is a matter of allowing for potential rewards through the creation of risk funds. A simple $100 billion climate tech fund that would disburse money to 120-odd companies in the Global South, including start-ups with clear roadmaps for scaling up climate tech, would greatly multiply the mitigation effect per dollar of its money.

Spotlight the climate-health-gender nexus: The climate conversation needs to be made personal, especially for the vast populations of the Global South. Women, for example, are most affected by climate change and serve on the frontlines of adaptation. They should lead the effort to counter it. Female leadership in the climate field is both practical and essential. Creating women-led projects investing in female leadership will allow for the conversation about climate to move from an elite 30,000-foot discussion to one related to the real requirements and concerns of households.

Women are also the most likely to bear the health impacts of climate-related hazards.

For countries across the world, public health systems will have to adapt and shift scale in response to new climate-related risks. Putting health at the centre of the climate conversation will also allow for a further personalisation of climate policy. It will create new reasons for and loci of climate action.

Multilateral forums such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the G20 must better acknowledge and differentiate impacts of climate change on health outcomes across genders and craft women-led initiatives to mobilise societal support for political action. It is essential to establish appropriate mechanisms that include and build capacities of this key population segment to shape global and national action on climate.

Build new pathways for cooperation: While traditional multilateral mechanisms – such as the UNFCCC and other organs of global climate governance – may have fallen short at times, there is nevertheless an opportunity for global action that transcends geopolitical divides. India’s approach to its G20 presidency prioritised consensus in contested times. Even at the height of geopolitical polarisation, every major country is nevertheless moving, for its own reasons and out of a sense of responsibility, to take national action on mitigation and adaptation. In other words, climate action is the location of “inadvertent cooperation” between great powers and the driver of greater regional dialogue as well.

It can and should be viewed as a mechanism for restoring global stability and trust in multilateralism – if, that is, parties live up to their own commitments. This inadvertent cooperation should be captured and energised through new partnerships, institutions and dialogues. Countries with the coincidence of capabilities and concerns can collaborate in smaller groupings for faster and more ambitious action. UN-led discussions may suffer from “zero-sum” approaches and offer outcomes with only minimal ambition. They offer a suitable location for the mutual blame game, but global climate action must proceed nevertheless and build on the national action and inadvertent cooperation that is already visible.

This co-authored article with Danny Quah was first published on the World Economic Forum (WEF) as part of its White Paper on ‘Shaping Cooperation in a Fragmenting World’.

Raisina Files 2024 – The Call of This Century: Create and Cooperate

This edition of the Raisina Files is infused with this conviction. The call of this century is to dispense with cynicism and to embrace what is appearing and emerging. A call to work towards inaugurating an inclusive and sustainable future. Rising up to the task requires us to create and cooperate, to build communities fit for this purpose.

This volume comprises contributions from an ensemble of thinkers who problematise, and attempt to answer, the pressing questions that matter. What are the power dynamics between a State and its citizens in this age of the digital? How do we protect our children in their always-online world, while preserving their agency and rights? If the current Western-led mechanisms of international aid are failing to meet the needs, how do we ensure that assistance truly reaches the grassroots? What transformations do our food systems require so they can be fit for the zero-hunger goal? As we move to the green frontiers, how will women lead the change? And how does the global financial system become just that—global?

Read it here.

Think20 India: Bridging the Ingenuity Gap

India assumed its G20 Presidency in the midst of global flux. Post-pandemic recovery efforts were uncertain and uneven; the Ukraine crisis had resulted in supply-chain bottlenecks and consequent global stagflation; and the perennial onslaught of the “elephant in the room”— global warming and climate change—had only exacerbated the challenges.

While unveiling the logo and the theme, PM Modi posited the country as an architect for a forwardlooking and result-oriented agenda for the world and the G20 as an exemplar of change, a vision for sustainability and growth, and a platform engaging with all that matters to the global south. Prime Minister’s vision, of drawing on India’s age-old ethic of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, strongly reiterated that inclusiveness and global cooperation would undergird India’s G20 Presidency.

A framework of 4Ds delineates India’s identification of its priorities as President—the promotion of decarbonisation, digitalisation, equitable development, and the deescalation of conflict. This approach is reflected across the thematic areas of Think20 (T20) India—the G20’s official Engagement Group for think tanks—which is often referred to as the “ideas bank” of the G20. The exchange of perspectives among high-level experts, research institutions, and academics that the T20 facilitates lends analytical depth and rigor to the G20’s deliberations. The T20, thus, institutionalised what Thomas Homer-Dixon calls “ingenuity” or the “production of ideas”, and helps bridge “the ingenuity gap”, i.e. the critical gap between the demand for actionable, innovative ideas to solve complex challenges and the actual production of those ideas.

The 4Ds are closely oriented towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As such, these framing ideas or principles are reflected across the T20’s seven Task Forces, which deal with ‘Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods’; ‘Our Common Digital Future’; ‘LiFE, Resilience, and Values for Well-being’; ‘Clean Energy and Green Transitions’; ‘Reassessing the Global Financial Order’; ‘Accelerating SDGs’; and ‘Reformed Multilateralism’.

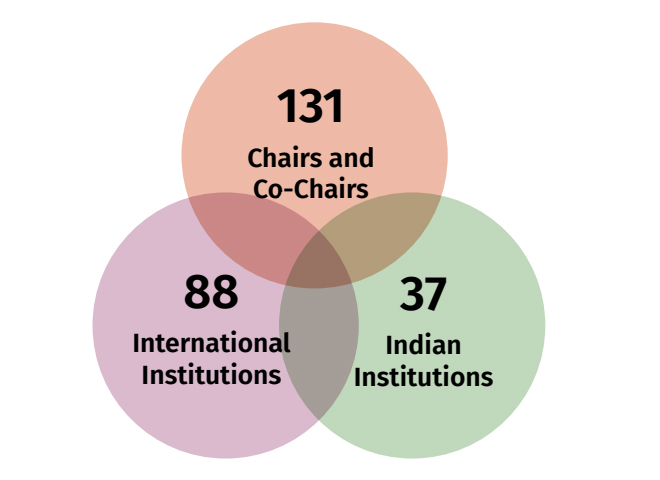

Constitution of Think20 Task Forces

The T20 Mid-Year Conference took place in Mumbai on 10-12 May 2023. Three hundred attendees and Task Force members from across the G20 countries deliberated on the seven selected themes and took stock of the T20’s achievements thus far and the road ahead. Two particular elements of T20 India’s research and engagements stand out—its focus on mainstreaming gender and promoting gender equality, and its efforts to ensure that the African continent is an integral part of all conversations. India, being the second of four successive emerging economies to lead the G20 (Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa will have been G20 Presidents between 2022 and 2025), has not only been a prominent voice of the Global South but has specifically put forth the unique developmental imperatives of the African landmass.

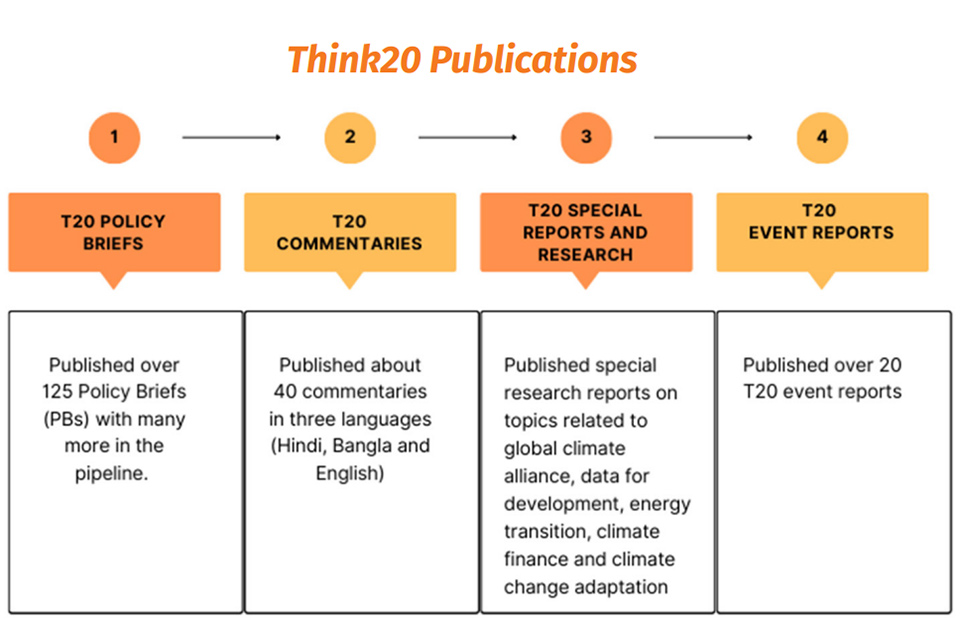

A key activity at the Mid-Year Conference was to finalise the Task Force Statements, which are vision documents about the Task Forces’ areas of engagement. The T20 Communiqué, a summary of recommendations to feed into the G20 process, is being drafted based on these statements and will be launched at the Think20 India Summit in Mysuru in August 2023. Moreover, as the term of the Indian T20 crosses its mid-point, it has already hosted over 50 events across the country and beyond and published over 125 Policy Briefs (PBs) with many more in the pipeline. These briefs are the outcome of processing raw ideas and producing them as actionable inputs.

The ethos of ‘Jan Bhagidari’ (or broad-based civic participation in governance) has underpinned the Indian Presidency’s efforts to take the G20 and its ideas to constituencies such as the youth, women, businesses, and civil society. Recognising the youth and women as essential partners in development and growth, the Mumbai Conference engaged actively with these target groups, and over 100 students from schools, colleges, and universities across Mumbai and Pune took part in the event.

The ethos of ‘Jan Bhagidari’ (or broad-based civic participation in governance) has underpinned the Indian Presidency’s efforts to take the G20 and its ideas to constituencies such as the youth, women, businesses, and civil society. Recognising the youth and women as essential partners in development and growth, the Mumbai Conference engaged actively with these target groups, and over 100 students from schools, colleges, and universities across Mumbai and Pune took part in the event.

India will prioritise data for development at G20

At the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Bali last month, Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi pledged that the principle of “data for development” will be integral to India’s G20 presidency. New Delhi’s commitment to this principle and its vision of strengthening it through international cooperation are already apparent. The first side event of the G20 Development Working Group under the Indian presidency, held in Mumbai on Tuesday, addressed the theme “Data for development: The role of the G20 in advancing the 2030 Agenda”. Amitabh Kant, India’s G20 Sherpa, emphasised that the country’s strategic use of data for governance and public service delivery in its aspirational districts, for instance, has, in three years, wrought a transformation that would otherwise have taken six decades. Data has also powered India’s pandemic response, innovations in education, health care, and food security, and enabled digital financial inclusion at a near-population scale.

As a group composed of developed and developing nations, the G20 presents a microcosm of what a concerted global effort to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) might resemble. If the G20is to help accelerate progress towards SDGs, it must vigorously pursue two kinds of data-driven interventions: Rejuvenating legacy datasets using Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Big Data analytics, thus converting data to intelligence; and using cutting-edge emerging tech — including drones, geospatial mapping, and AI — to generate futuristic new datasets.

The country is about to launch a major data initiative as a part of which it will share anonymised data sets collected under the National Data Governance Framework with the AI ecosystem, and the research and startup communities.

In both areas, India has much to offer the world. The country is about to launch a major data initiative as a part of which it will share anonymised data sets collected under the National Data Governance Framework with the AI ecosystem, and the research and startup communities. This vast database will be used to train AI models, catalyse innovation, and craft more effective policy and on-ground solutions. In May, NITI Aayog launched the groundbreaking National Data and Analytics Platform to democratise access to public government data by making datasets accessible and interoperable, and providing accompanying tools for analytics and visualisation. Each of these initiatives builds upon the PM’s vision of a Digital India characterised by a digitally empowered society and tech-enabled knowledge economy.

The creation of entirely new datasets is also exploding in India. Drones are scanning the country’s terrain in minute detail, and this aerial footage is being combined with other kinds of data to create extraordinarily detailed maps. Data generated by drones is also revolutionising agriculture and helping transform existing cities into smart cities. The World Economic Forum estimates that the new data economy resulting from drones could boost India’s Gross Domestic Product by $100 billion and create nearly half a million jobs in the coming years.

Indeed, India is rapidly emerging as a world leader in the geospatial sector. Addressing the United Nations World Geospatial Information Congress in Hyderabad in October, PM Modi emphasised that geospatial technology is a “tool for inclusion” that has been “driving progress” and established itself as an enabler across development sectors. In fact, this is a space in which India has already begun to support its South Asian neighbours with communications and connectivity.

Across nations, data must be emancipated from its current silos, and progressively larger volumes of data must be made public and easily discoverable.

As India and its G20 partners forge collaborations centred on data for development, they should adhere to certain core principles. Across nations, data must be emancipated from its current silos, and progressively larger volumes of data must be made public and easily discoverable. To be used effectively, data must be simple, high-quality, and offered in real-time. A culture of experimentation and innovation must be fostered around data operations, and countries must invest in tools for analysing datasets in creative ways. To enhance outcomes, constructive competition could be promoted among stakeholders in the data ecosystem.

Two crucial tasks lie before the G20. Its members will have to try and arrive at a common understanding of sensitive and non-sensitive data, and to reflect on frameworks that could help share data across borders. There is an in-principle consensus that open repositories should be built where nations can store public-value data. But a prudent balance will need to be struck between the imperatives of data sovereignty and protection, and the notion of a data commons that could benefit the global community. Ultimately, the G20’s data regulations should embed the norm of reciprocity — nations should be able to share and benefit from development data.

A culture of experimentation and innovation must be fostered around data operations, and countries must invest in tools for analysing datasets in creative ways.

As 2030 nears, the Indian presidency could be an inflection point for the G20’s deliberations around data for development. Since 2019, the theme’s importance has been consistently reaffirmed by G20 leaders, and the recent Japanese, Saudi Arabian, Italian and Indonesian presidencies have all recognised that the wealth of data produced by digitalisation must be harnessed. But government-to-government dialogue must increasingly be supplemented by systematic engagements with the private sector, civil society, women and young people, if data-led empowerment is to be mainstreamed. This is a key element India could underscore in the G20 playbook, thus shaping past achievements and present priorities into what could become a part of the grouping’s legacy to the world.

Enough Sermons on Climate, It’s Time for ‘Just’ Action

As Britain readies to host the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow in November this year, there is a concerted effort to push countries towards publicly endorsing and adopting ‘Net Zero’—a carbon neutral emission norm—as policy. This is a demand for an inflexible, near-impossible, time-bound agenda to achieve what is no doubt a noble goal. And, as is often the case with climate-related issues, the nobility of intent is at risk of being overwhelmed by sanctimonious hectoring that raises hackles instead of ensuring meaningful participation.

On 3rd March, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres took to Twitter to call on governments, private companies and local authorities to immediately initiate three measures to mitigate climate change: Cancel all coal projects in the pipeline; end coal plant financing and invest only in renewable energy; and, jumpstart a global effort to a ‘just transition’ from carbon to non-carbon energy sources.

On the face of it, this was an unexceptionable call from the high priest of the UN to the global laity to rise in support of an important cause. But if we were to scratch the surface of the Secretary-General’s words, we would see that his call was little more than virtue-signalling.

For, there is nothing ‘just’ about the transition that he has sought without delay. Implicit in his call is the immoral proposition to disregard poverty, despair and the yawning development deficit between nations as he places them all on the same plane. Inherent in this approach is the unedifying complicity of global institutions in foisting an arrangement founded in the belief that the poor in the developing world should underwrite the climate mitigation strategy of the developed world. The climate high priests need to realise that depriving the world’s poorest of their aspirations can never be ‘just’ climate action. It can be convenient and, hence, it has much appeal in many quarters.

The climate high priests need to realise that depriving the world’s poorest of their aspirations can never be ‘just’ climate action. It can be convenient and, hence, it has much appeal in many quarters

An Alternative Script

A waffle-free alternative script for those given to sermonising to the world would focus on three other aspects that may actually lead to faster transitions and more justice. First, an impassioned call to those who control capital—managers of pension, insurance and other funds—to ensure larger amounts of money leave the country of origin and flow to countries of deficit for building sustainable, climate resilient infrastructure of the future. The Climate Policy Initiative has calculated that less than a quarter of climate finance flows across national boundaries; in other words, the overwhelming majority of climate finance is raised for domestic projects. The states expected to disproportionately do more to battle climate change are located in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Yet, they are inadequately funded and financed and cost of capital in these places dampens the scope of action. It would be stressing the obvious to say that the frontline states cannot be expected to engage in this battle without adequate inflow of climate capital at the right price for climate action.

Second, the assessors of risk—the intractable credit rating agencies, the cash-rich central banks and the big boys of New York, London and Paris—who decide how much capital should flow in which direction, should be called upon to recalibrate their risk assessment mechanism. Let it be said, and said bluntly, that objective ‘climate risk’ outweighs subjective ‘political risk’ which prevents the flow of capital to key climate action geographies. Risk must be reassessed objectively. Till then, the highfalutin sermons of the Pontiffs of Climate would be mere lip service, which none among the Climate Laity would bother to take seriously.

Third, and, perhaps, the most ‘just’ proposition the Secretary-General could make, would be a moral directive to all Western nations to shut down coal plants and fossil fuel- based enterprises immediately and entirely abandon carbon-fuelled energy for any purpose. After all, green energy sources need room to grow and space to mature and the OECD nations must allow this at warp speed. It is farcical to deny coal plants to countries that are still struggling to claw their way up the development ladder and demand that they turn carbon neutral while thousands of units and homes belch and blow climate emissions every day in rich economies. What is good for the rich cannot be bad for the poor.

Rich countries have failed to reduce their share of fossil fuel emissions. CSEP’s Rahul Tongia has calculated that the top emitting countries in terms of per capita emissions (nations above the global average emissions) still account for about 80 per cent of global Fossil CO2. He further explains that the absolute emissions of these countries are rising even when measured in 2019. The rich took more than their fair share historically, and are still doing so. Any ‘Just Transition’ must involve evicting the squatters occupying carbon space to the detriment of others. Buying this space from the poorer is not ‘just’; it is another perverse business model based on extraction and mercantilism of centuries past.

Any ‘Just Transition’ must involve evicting the squatters occupying carbon space to the detriment of others. Buying this space from the poorer is not ‘just’; it is another perverse business model based on extraction and mercantilism of centuries past

In the run-up to COP26 at Glasgow, we are witnessing a new passion play of countries making a dramatic show of embracing the idea of Net Zero economies in the coming decades. The script of this passion play draws on starkly evocative narratives that seek to catalyse action through theatrical terms such as ‘climate emergency’. From appropriating the voice of the powerless to acquire legitimacy and crafting compelling narratives through a new cohort of well-funded ambassadors to push the envelope on climate change policy approaches, we are seeing varied actors engaging with climate issues in different ways. These different efforts have a common design, the economic objective of socialising the cost of climate action and making the poor carry the can for the rich.

That said, some facts are irrefutable. The last decade has been the warmest in recorded human history and its effects are visible to all. In February this year, an iceberg larger than New York City broke off the frozen Antarctic and my just be a prelude to what lies ahead. Indeed, the possibility of the Arctic turning into a benign waterway in the near future can no longer be ruled out. It would require extraordinary un-intelligence to argue that global warming and its fallout can be mitigated by business-as-usual decision-making. But even as there is trans-world consensus on climate change and its impact, many would and must disagree on the proposed burden-sharing and distribution of responsibilities as we respond as a collective.

The India Imperative

India will be significantly affected by climate change in the coming decades. It is already feeling the heat and is combatting challenges from its mountains to its coasts due to shifting weather cycles and changing climate. It needs clearheaded policies, backed by political will, on this single most important issue that will impact its growth, its stability and the very integrity of its geography comprising a multitude of topographies.

This is happening at a moment when India is poised to exit the low-income orbit and take off on a trajectory towards becoming a middle-income country. Its journey from a US $3 trillion economy to a US $10 trillion economy coincides with ongoing climate action, polarising climate debate and climate-impacted economics. India can neither isolate itself from this reality, nor can it be reticent or timid in making its choices known to the world. India cannot be a receiver of decisions made elsewhere; it has to be on the high table, co-authoring decisions implicating its future.

For India, the moment offers three opportunities in these challenging times. First, India has to prepare itself through its policies, politics and internal rearrangements to seize and realise the single biggest global opportunity of leading a global effort to mitigate emissions of the future. The IEA, in its India Energy Outlook 2021 Report, estimates that India’s emissions could rise as much as 50 percent by 2040—the largest of any country, in which case India would trail behind only China in terms carbon dioxide emissions. This need not happen and is an opportunity for India and the World.

India must grab this chance to lower its future emissions through the right investments, technologies and global partnerships. The developed world, too, must make a matching response: Just like the Marshall Plan invested billions to rebuild post-War Europe with Germany at its heart, a new age Climate Marshall Plan must see India at its core. India must prepare and offer itself as the single biggest climate mitigation opportunity for the world and the most important green investment destination.

The developed world, too, must make a matching response: Just like the Marshall Plan invested billions to rebuild post-War Europe with Germany at its heart, a new age Climate Marshall Plan must see India at its core

Second, neither the world nor India should forget the dictum that on climate, India solves for the world. The solutions that India experiments with and implements successfully will be fit to be repurposed for other developing countries with similar geo-topographical conditions and economic sensitivities. Many of them are frontline countries in the climate battle.

India can and must become the hub of climate action for this decade and beyond, offering services, technology and infrastructure through climate supply chains that span the developing world. The International Solar Alliance is just a modest beginning. The future holds multiple opportunities. The country must lead the charge through building financial institutions that will support and sustain green transitions and helping create green workforces fit for purpose for the coming decades, amongst others.

Third, as India celebrates 75 years of its independence in 2022 and leads the G20 in 2023, it has the chance to make its most significant identity shift. India moved from being a British colonial state to a free nation in 1947, and then moved from being perceived as a land of snake-charmers to becoming an internationally acknowledged technology hub at the turn of the century. This decade offers the chance for it to emerge first as aUS $5 trillion and then as aUS $10 trillion economy that will be green and low carbon in its evolution – the first large green economy of the fourth industrial revolution.

India’s expectations from Glasgow COP26 should be uncluttered—its single purpose must be to catalyse global flows and investments to India and other emerging economies. If India fails to attract investments, the markets will clearly have not signed on to the climate agenda. In this effort, India needs a leg-up from the Climate Pontiffs.

Perpetuation of global poverty and low incomes cannot be the rich world’s climate mitigation strategy. ‘Net Zero’ should not seek this end state. On the contrary, investing in the emerging world’s green transition is the only way to build a ‘just’ world. The UN Secretary-General could help ensure that the largest pool of new money flows to where the climate battle will be fought—in India and in the emerging world. That would be a just transition and an efficient one.

If the EU fails, we can say goodbye to the liberal order

Eastern Focus: To what extent is Europe important for the future of the world order? Europeans feel like they count less and less on the world scene.

Samir Saran: Europe is, paradoxically, the single most important geography that will define the future trajectory of the global order. If Europe remains rooted in its fundamental principles – of being democratic, open, liberal, plural, supporting a transparent and open market economy, defending rule of law, the rights of individuals, freedom of speech – the world will have a chance of being liberal. If the European Union is split between the north and south, east and west and we see a large part of it deciding to give up on the Atlantic project and align with more authoritarian regimes – which is quite tempting, due to the material side attached to the choice – that will be the end of the Atlantic project. An EU that is not united in its ethics is an EU that will eventually write its own demise. How will Europe swing? Will it be an actor, or will it be acted upon?

I have the belief that post-pandemic EU, as a political actor, will see a new lease of life. A new political EU may be born as the pandemic ends. Unless that happens, I believe this is the end of the European Union itself. It is a do it or lose it moment. Unless Europe becomes strategically far more aggressive, far more expansive, aware of its role, obligations and destiny you will see an EU that fades. For me, the most important known unknown is the future of Europe. Will the EU hold? Will the 17+1 become more powerful than the EU 27? Which way will the wind blow on the continent? Will it really be the bastion of the liberal order or will the liberal order be buried in Europe?

The Indo-Pacific is the frontline for European safety

EF: We’ve been used to only existing as part of the transatlantic relationship. In the past few decades, Europe has never really seen itself as an individual actor, but rather in coordination with the US. That is something that is starting to shake now. Do you see Europe acting on its own terms, as a global actor, in the positive case in which the member states do get their act together? Are we rather going to continue to act together with the US? Or find some other partners?

SS: I suspect that with Brexit, you might see a far more cohesive EU, organised around the French military doctrine and French military posture. With an absent UK, I have the feeling that the political cohesion of the EU will increase and that the EU will be far more coordinated in its approach to the geostrategic and geopolitical questions. France realises that by itself, without the size of the EU, it might not be a significant actor. A French military presence will be compelling only if it acts on behalf of the EU.

Europe believed that it could change China by engaging with them, however I suspect China will change the EU before the EU changes China.

In terms of other partners, Europe has made one error. Europe believed that it could change China by engaging with them, however I suspect China will change the EU before the EU changes China. The mistake that the EU makes is that it imagines that an economic and trading partnership will create a degree of political consensus in Beijing. Nevertheless, Beijing is not interested in politics, but in controlling European markets.

What Europe should do is to consider the importance of India. If the European continent needs to retain its plural characteristics, South Asia is the frontline. What is happening today between India and China is actually a frontline debate on the future of the world order. The Himalayan standoff is just the first of the many that are likely to happen unless this one is responded to. If China is able to change the shape of Asia and recreate the hierarchical Confucian order, don’t be surprised if the fate of Europe will follow the same path. If Europe needs to feel secure in its own existence it needs to create new strong local partnerships – with India, Australia, Indonesia, Japan. The EU needs to see itself as an Indo-Pacific power. The Indo-Pacific is the frontline for European safety. If the Indo-Pacific was to go the other way, the mainland is not going to be safe.

EF: What do you think about the CEE’s role in the new emerging order? We see an increased competition for hearts and minds here. How could India help, in an environment of increased competition and active engagement of China in this space?

SS: The Central Europeans are going to be the centre of attention for many actors. China will buy their love, America will give military assurances and so on. In the near future, many actors will realise the importance of the CEE, simply because it is these countries that will decide which way Europe finally turns. In some ways they are the swing countries, the swing nations that are going to decide whether Europe remains loyal to the ideals of its past or decides to have a new path. CEE countries are in many ways the decisive countries.

CEE has two important options and two important pressures. The options: will they be able to create a consensus (between the Chinese, the Russians, the Old Europe and the new countries like India) or will they be an arena for conflict? Can we create a ‘Bucharest consensus’, where the East and the West, North and the South build a new world order and the new rules for the next 7 decades? If you play it wrong you might become the place where the powers contest, compete and create a mess.

There are also two pressures. Firstly, there is an economic divide in Europe. You are at a lower per capita income, you need to find investment funds for the infrastructure, employment, livelihoods and growth, which results in an economic pressure that needs to be tackled. Therefore, Europe will have to decide if the provenence of the money matters. Does it matter if it is red or green? Does it matter if they come from the West or the East? That is one pressure that needs consideration. How do you meet your own aspirations, while being political about it?

The other pressure is the road you want to take. How do you envisage the future? Is it going to be a future built on cheap manufacturing? Being an advanced technological society, are you going to be the rule-maker of theFourth Industrial Revolution or its rule-taker? Secondly, the nature of the economic growth that you are investing in becomes another pressure. This is the second choice that the CEE will have to make. In that sense, I believe that India becomes an actor. As we have experienced this in the past 20 years, we are one of the swing nations that could decide the nature of the world order, thus we may share this experience with you. We have also decided that we don’t want to be a low-cost manufacturing economy like China, but rather a value-creating economy, building platforms. Even if we have a small economic size, we have a billion-people digital platforms, digital cash system, AI laboratories and solutions.

What is happening today between India and China is actually a frontline debate on the future of the world order. If China is able to change the shape of Asia and recreate the hierarchical Confucian order, don’t be surprised if the fate of Europe will follow the same path.

As we move into theFourth Industrial Revolution, the tyranny of distance between Europe and India disappears. We don’t have to worry about trade links, land routes and shipping lines. Bits and bites can flow quite rapidly. As we move to the age of 3D printing, to the age of quantum computing, of big data and autonomous systems, the arena where we can cooperate becomes huge.

India gives Europe room to manoeuvre, room to choose. When it comes to choosing, besides the traditional American and Chinese propositions, there is also a third one – India, a billion-people market.

EF: Do you expect that there is going to be a shift in the EU toward reshoring and ensuring that manufacturing is not captive to Chinese interests or to Chinese belligerence?

SS: I think that we are going to see a degree of reshoring everywhere. It is not going to be only a European phenomenon. Political trust is going to become important. Political trust and value-chains are going to affect one another. Countries are going to be more comfortable with partners who are like-minded. They don’t have to agree on everything, but they should be on the same ideological and political spectrum.

There are two reasons for this. One is the pandemic that we are currently facing and in a way it exposed the fragility of globalisation as we know it. The hippie and gypsy styles of globalisation are over. I think that people are going to make far more political decisions. The second is that as we start becoming more digitalised societies, individual data and individual space are going to be essential, thus you don’t want those data sets to be shared with countries whose systems you don’t trust. Value is going to increasingly emerge through intimate industrial growth, far more intimate in character – it is going to be about the organs inside your body, it is going to be about the personal experiences, about how we live, transact, date or elect. They are all intimate value chains. The intimate value-chains will require far greater degree of thought than the mass production factories that created value in the XXth century.

The EU may be setting the format for managing our contested globalisation

EF: You mention the rising value of trust, as a currency even. In Europe, we often point out that we are an alliance based on values. But even our closest partner, the US seems to be moving in a much more transactional direction, let alone China and others. You are describing a worldview that is relying increasingly on shared values, at least some capacity to negotiate some common ground, on predictability, whereas in many ways it seems that things are moving in the opposite direction, a much more Realpolitik one. Is this something that is going to last?

SS: The pandemic has brought this trend to the fore. People are going to appreciate trust and value systems more than ever. But I think this was inevitable. If you would recall, India used to be quite dismissive of the EU, calling it “an Empire of gnomes”, with no strategic clout. But if you look at the last two years, India has started to absorb, and in a sense to propose solutions that the EU itself has implemented in the past. India came up with an investment infrastructure framework in the Indo-Pacific that should not create debt trap diplomacy, should create livelihoods, respect the environment and recognise the rights and sovereignty of the people. India came up with this when it saw that the Chinese were breaking all rules and all morality to capture industrial infrastructure spaces. The Americans under Donald Trump also came up with the Blue Dot American project for the Indo-Pacific – a framework that was based on values. Whenever you have to deal with a powerful political opponent you throw the rule book in there. If you don’t want to go to war with them, you will have to manage them through a framework of laws, rules and regulations. The value systems are a very political choice. They are practices and choices enshrined in our constitutions and foundational documents. Therefore, dismissing values and norms as being less political or less muscular is wrong. The EU, “the empire of gnomes” that was much criticised for the first two decades as weak and not geopolitical enough, may well become an example for other countries. If it remains solvent, a vibrant union, and if it is not salami-sliced by the Chinese in the next decade, the EU may well be setting the format for managing our contested globalisation.

This pandemic is the first global crisis where Captain America is missing

EF: How does India see the future of the Quad? Usually the Quad is associated with a certain vision of the Indo – Pacific, free from coercion and open to unhindered navigation and overflight. Are we going to see the emergence of a more formal geopolitical alignment or even an alliance to support a certain vision about Asia?

SS: The Quad is going to acquire greater importance in the coming years. It is going to expand beyond its original 4 members. We’ve already seen South Korea and the Philippines joining the discussion recently. We are going to see greater emphasis by all members doing a number of manoeuvres, projects and initiatives together. The next 5 years will be the age of the Quad. The pandemic started this process. I see three areas where the Quad can be absolutely essential.

One is in delivering global public goods, keeping the sea lines open and uncontested so that trade, energy and people can move with a degree of safety and stability. In a sense, I see the Quad replacing the Pax Americana that was underwriting stability in certain parts of the world.

The second area is going to be around infrastructure and investments in certain parts of the world. I see the Quad grouping many initiatives that will allow for big investments in countries which currently have only one option – China. The Quad will be able to spawn a whole new area of financial, infrastructure and technology instruments closer to the needs of Asians, South Asian, East African, West Asians including the Pacific Islands. The Quad will be the basis of this kind of relationships in the upcoming years.

Thirdly and most importantly, the role of the Quad will be to ensure that we won’t reach a stage where we have to reject the Chinese. None of us wants a ‘No China’ world, because all of us benefit from China’s growth and economic activities. Many of us have concluded that the only way to keep the Chinese honest in their engagements, economical or political, is to be able to put together a collective front in front of them, not negotiate individually. The EU has done that longer than anyone else and that’s why the Chinese don’t like the EU and apply a ‘divide and conquer’ methodology to get more favourable deals. The Quad is in many ways an expression of that reality, as well of that the middle powers in Asia and Pacific (Indonesia, Australia and Japan) will have to work together, sometimes without the Americans, to negotiate new terms of trade and new energy, or technological arrangements. The Quad in many ways is also the ‘make China responsible’ arrangement, an accountability framework which will keep the Chinese honest and responsible actors in the global system.

The next 5 years will be the age of the Quad. The Quad in many ways is also the ‘make China responsible’ arrangement, an accountability framework which will keep the Chinese honest and responsible actors in the global system.

EF: Do you also see this trend extending into the political sphere in a kind of collective endeavour both in Asia (through the Quad) and in the West (starting with Europe perhaps) to build a new kind of world order? Do you feel that this ‘middle powers concert’ is one possible way to go? Or do you believe that we are going to be disappointed, as we were by the BRICs, when some of the members drowned in their own domestic problems?

SS: We are part of a world that doesn’t have any superpowers. The last superpower was America, and that ended with the financial crisis ten years ago. Ever since, we have been literally in a world which had quasi-superpowers like the US, to some extent Russia, the Chinese, but there was no real hegemon that could punish people for bad behaviour and reward people for good behaviour.

Some of the most interested actors in the Indo-Pacific in the last two to three years happened to be the UK and France. A few years ago, they sensed that if they want to be relevant in the future world order, as it is built and as it emerges, they need to be present in the debates that are unfolding in this part of the world. Both partnered with India – to do military manoeuvres, to create maritime domain awareness stations, to invest in infrastructure and to create clearly the beginnings of a new order that might emerge from here. We will have to create these coalitions to be able to get things done.

The pandemic tells us something which is also quite tragic. Ever since I was born I have never witnessed a global crisis that did not have America as a response leader. This pandemic is the first global crisis where Captain America is missing. What makes it even more complicated is that the successor to Captain America has caused the crisis. Hence, you have the old power, which is absent and engrossed in its own domestic realities, and the new power that has been irresponsible and has put us in this position. Both the previous incumbent and the new contender don’t have the capacity to take action in this world by themselves. This tells us that building a coalition of middle powers is absolutely essential. It is not a luxury, it is not a choice. This is something concerning our own existential reasons that we must invest in.

EF: Do you see this coalition of middle powers as some sort of a ’league of democracies’? It is a concept that was previously advanced by John McCain and now Joe Biden is embracing as his overarching framework for foreign policy. Do you see the potential for creating this league of democracies as some sort of manager and defender of the liberal international order?

SS: I think it is inevitable. Technology is so intimate that we are not going to trust our data with folks we have a suspicion about. Thus, it is this reality that makes this coalition of democracies and like-minded countries inevitable. Even if we may never call it that, it is going to become that. We are going to notice countries engaging in these intimate industries with others who are similar, who are like-minded, who have similar worldviews. Still, this process may take longer than we have. We do not have the luxury of time, because we are going to be destroyed, divided, decimated and sliced in the meantime.

A few countries will have to take leadership – either the French, the UK, the EU itself, or India, or all of them. Until there is an agreement on a big vision for the new world order we must agree to an interim arrangement and have to create a bridging mechanism that takes us from the turmoil of the first two decades of this century to a more stable second half of the century. We don’t want to go through two world wars in order to achieve this unity, as we did in the past century. We need to have some other mechanisms that will prevent conflict, but preserve ethics.

In this context the EU-India and the CEE-India projects are essential. It is us who have the most at stake, because our future is on the line. The more the world is in turmoil, the less we will be able to grow sustainably. It is our interest to create and invest in institutions and informal institutions that could preserve a degree of values and allow for stability.

Such a coalition reuniting countries from Central Europe, Western Europe and from Asia (such as India, Australia, Japan) will normalise the behaviour of both America and China. I do not think that they behaved responsibly in the last few years – one because of its democratic insanity, and the second because of its absolutist medieval mindset. Along these lines, you have democratic failure at one end and a despotic emergence at the other end. We need to ensure that democracy will survive and that the middle powers will be able to normalise this moment.

EF: What is Russia’s role in all this? Is Russia going to be on our side? Or is it going to be on China’s – considering that sometimes they seem to, although their agendas perhaps align only when it is opportune for both of them?

SS: Russia has an odd reality. It is a country that has a very modest GDP (the second smallest within the BRICs) but it is also a country that is possibly the second most powerful military force in the world. A big military actor with a very small economic size. This is creates a policy asymmetry in Moscow. It has very little stakes in global economic stability or global economic progress, but it has huge clout in the political consequences of developments around the world. The Russians have somehow to be mainstreamed into our economic future. Unless Russia is going to have an active role in the Fourth Industrial Revolution or have real benefits, their economy will stay in the 20th century and therefore their politics is going to reflect a 20th century mindset. If they are included in the economic policies of the future, their politics will evolve too. It is not an easy transition. Nevertheless I would argue that the Russians have to be given more room in European thinking so that they don’t feel boxed into the Chinese corner. The last thing that we should be thinking of is giving Russia no option but to partner with the Chinese. Perhaps the immediate neighbours (the CEE) will not be open to a partnership, taking into account their political history. But countries like India would be able to offer space for manoeuvre. In that sense, India could be a market, a consumer, an investor in the Russian economic future and the CEE-India partnership could become important. Can we together play a role in normalising that relationship? Can we give the Russians an option other than China? If Russia’s economic future is linked to ours, it doesn’t have to be in the Chinese corner. The Russians are not the Chinese. The Chinese take hegemony to a whole new level; the Russians have this odd asymmetry that defines their place in the world. This asymmetry should be addressed with new economic possibilities and incentives.

The rise of the Middle Kingdom

EF: We’ve been discussing how to react to a world that is increasingly defined by China. But what are China’s plans? What does China want?

SS: I do not know their plans, but I can tell you how I see China’s emergence, from New Delhi. I define it through what I call the 3M framework.

Firstly, I see them increasingly becoming the Middle Kingdom. Chinese exceptionalism is defined in those terms. They believe they have a special place in the world – between heaven and earth. They will continue to defy the global rules and they will not allow the global pressures to alter their national behaviour or domestic choices. So we will see the first M, the Middle Kingdom, emerge more strongly in the years ahead.

This pandemic is the first global crisis where Captain America is missing. What makes it even more complicated is that the successor to Captain America has caused the crisis.

Secondly, this Middle Kingdom will make use of modern tools. They see Modernity as a tool, not as an experience. In that sense they use it to strengthen the Middle Kingdom, not to reform and evolve. Such tools include digital platforms, the control of media and a modern army with modern weapons to control and dominate.

Thirdly, the final M deals with a Medieval mindset. They are a Middle Kingdom with Modern tools and a Medieval mindset that believes in a hierarchical world. We are a world which has moved away from the hierarchies of the past. The world is more flat, people have equal relationships. The Chinese don’t see it like that. They see a hierarchical world, where countries must pay tribute to them. They sometimes use the Belt and Road Initiative to create the tribute system or the debt trap diplomacy to buy sovereignty. Likewise, they use other tools to ensure the subordination of the countries they deal with.

These three Ms are defining the China of today.

This interview appeared in The Eastern Focus

US-India Partnership for a Green Future

Climate change is one of the most formidable challenges for this young century. As the World Economic Forum’s The Global Risks Report 2020 makes clear, failure to mitigate and adapt to climate change is the single most impactful and second-most likely risk facing the international community over the next 10 years. How effectively governments, businesses and societies can work together to make a tangible impact on this global challenge will determine the future of our planet.

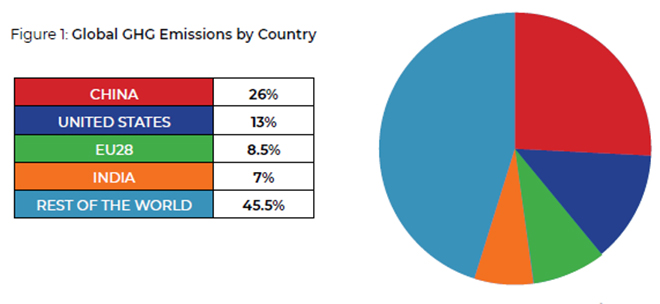

As shown in Figure 1, the United States (US) and India contribute almost 20 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Although the two countries differ markedly in both per capita emissions and incomes, India and the US must take concrete action according to their capabilities to develop solutions that can boost economic growth and mitigate the catastrophic consequences of climate change. The best way to achieve these twin goals is to invest in infrastructure for a resilient and low-carbon future; cooperate in key areas that produce relevant knowledge; foster innovation exchange; strengthen technical assistance bilaterally and for others; and catalyse capital investments for energy access, energy efficiecy, and renewable technologies.

Both the US and India have taken important strides together to advance their strategic partnership in the domain of climate action and policy. However, existing efforts continue to rely mainly on an incremental approach to tackling climate change. Such measures are welcome but insufficient. As the world grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, we are reminded of the human and economic costs associated with weak international cooperation, delayed action, and the lack of investments in important infrastructure and capabilities. Climate-induced disasters may make the current pandemic look meek, and the world could ignore this risk at its own peril. Thus, it is vital for India and the US to double down on efforts to drive structural change, hurdle institutional barriers, and overcome the inertia inhibiting green growth and development.

In line with these goals, the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and The Asia Group (TAG) convened a joint roundtable in October 2019 to advance recommendations to strengthen the US–India partnership for a green future with a special focus on climate mitigation, renewable energy, and climate financing. Across these topics, it is clear that both countries face a number of complex and overlapping challenges and opportunities. Even as recent policy efforts have strengthened each country’s capacity to tackle these challenges, this report seeks to identify policy recommendations to support this progress.

In the lockdown, a breath of fresh air

One of the few positive spin-offs of the ongoing nationwide lockdown to combat Covid-19 has been a dramatic reduction in air pollution. Recent Nasa data reveals that air pollution in north India has dropped to a 20-year low. In Delhi, the levels of harmful microscopic particulate matter, PM 2.5, plunged after the lockdown began — falling from 91 mg per cubic metre (mg/m3) on March 20, to 26 mg/m3on March 27.

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) released by vehicles and power plants also saw a significant fall of 71% during the period. The air in Delhi is now clear, the skies are blue, and we can hear birdsong again on the boulevards.

Unfortunately, these are but temporary gains, and should not distract us from the dangers of air pollution.

An urgent warning comes from a Harvard University study (bit.ly/3dthqiv), which establishes a correlation between long-term exposure to air pollution and Covid-19 mortality. The study finds that people living in polluted cities are more likely to have compromised respiratory, cardiac and other systems — and, therefore, are more vulnerable to Covid-19.

We should be very worried because India has 21of the 30 most polluted cities in the world. Air quality in some of our cities is 10 times over the safe limits recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and, as per some estimates, air pollution claims more than one million lives each year.

Therefore, even as India flattens the infection curve, addressing the air pollution problem should continue to be a high priority for all policymakers. Today’s cerulean skies remind us that clean air and the right to breathe must be available to all citizens. And if India were to achieve this, there will be huge collateral benefits. We would not only become much more globally competitive, but we could also be well on our way to exceeding our climate ambitions outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

There are many ways in which an economic revival package can get India to this Green Frontier. For instance, new investments could be directed towards renewable energy, with larger allocations and subsidies to initiatives like the National Solar Mission. We could adhere to deadlines for the Bharat Stage 4 standards and accelerate timelines and infrastructure investments for electric vehicle (EV) adoption.

Large electric battery factories could be established to enable localised energy storage solutions. Bailouts and incentives to the auto, aviation and construction sectors could encourage green transitions and clean air ambitions. The Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) in the residential sector could be enforced and a 2011policy relating to energy efficiency in MSME clusters could be integrated with the fiscal support to this sector.

Global experience suggests that crises create political opportunities for embracing change. After the 2008 global financial crisis, China spent nearly a third of its $568 billion stimulus towards projects that addressed environmental goals. China has since become a global leader in solar, wind and hydropower markets.

Britain and Germany also undertook green transformations post 2008 crisis. Similarly, India could use this Covid-19 crisis to undertake a far-reaching green revival.

We will find support. After the Covid-19 pandemic, there is a renewed focus on mega black and white swan shocks that can lead to immense loss of lives and destroy trillions of dollars of economic output. It is now much easier to convince policymakers, bankers and investors that awarming climate may well be the single-biggest macro shock the world will have to face. Green revival packages are bound to emerge around the world and global finance will inevitably align to this endeavour.

India is already the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs). Even optimistic predictions suggest that our emissions will nearly double in the next decade or so. A green revival package could be designed to ensure that India’s post-Covid economic resurgence becomes a key contributor in mitigating global emissions. It must be branded as the single-most important initiative for the world to meet and exceed Paris Agreement goals.

This will also give India more leverage in influencing the global financial community, and compel them to more pragmatically price risk, transparently rate creditworthiness, and bring down regulatory barriers that restrict the flow of capital to green projects in the developing world.

The battle for clean air requires structural reforms across multiple sectors, institutions and processes.

Public and private funds need to be redirected to green investments.

While temporary reductions in noxious emissions are certainly a huge relief, they are not the panacea for a country that has the onerous task of becoming the first $5 trillion economy in a carbon-constrained world. And, we must do this without gasping for breath.

ORF takes on the budget

The allocation for health of around INR 63,540 crore is about a 13% increase from last year. Much of it has been to PMJAY, the flagship scheme of the government, which saw allocation rise from INR 2,400 crore last year to INR 6,400 crore in the interim budget. Ayushman Bharat’s second arm, the HWCs also got considerable hike in budget allocation — from INR 1,200 crore to INR 1,600 crore. FSSAI as well as the National AIDS Programme have also seen improvements in allocation.

However, an exclusive focus on PMJAY can result in a possible de-prioritisation of core health system functions, with slow-down or reduction of allocations under various heads, including NHM. Capital outlay on medical and public health, for example, has come down from 3047.67 crore in 2017-18 (actual) to 2391.33 crore in 2018-19 (RE) to 1675.90 crore in 2019-20. This can potentially impact health system’s capacity to expand in areas that need health services the most. Neglected areas can remain neglected unless there is specific focus. The budget document stated that of the 3,508 HWCs already operational, only 582 are in the aspirational districts, or the districts lagging in health development.

An exclusive focus on PMJAY can result in a possible de-prioritisation of core health system functions, with slow-down or reduction of allocations under various heads, including National Health Mission.

Lastly, it is easy to celebrate the INR 6,400 crore allocation, meant for around 50 crore PMJAY members. Still, the money allocated remains around INR 1,000 crore short of a conservative estimate of PMJAY spending this year. To put things in perspective, healthcare coverage to just around 35 lakh CGHS beneficiaries will cost the exchequer INR 3,000 crore, of which INR 2,850 crore was allocated in the interim budget. In addition, delays in payment of sanctioned amounts undermining efficiency of PMJAY remains a real risk, as with many health schemes. As of now, reports indicate that of the INR 2,400 crore allocated last year for PMJAY by the MoF, INR 1,000 crore has yet not been released, and that there are outstanding payments from the Centre to the States amounting to INR 1,700 crore under PMJAY. This can potentially impact the sustainability and effectiveness of the scheme.

It was decided by the government that India’s government health spending will be 2.5% of its GDP by 2025. At the current pace, it will be impossible. As a percentage share of total budget, the interim budget outlay on health was just 2.2%, below the figure in 2017-18, where the proportion of health outlay peaked under the Modi regime at 2.4%. Health in India needs significant additional resources, and not reallocation of existing resources. Ayushman Bharat becoming the flagship health initiative cannot and should not lead to a case of the government missing the forest for the trees. Without expansion of real health infrastructure, Ayushman Bharat will be just band-aid.

AI and automation technologies

The Union Budget 2019 signals early forays into artificial intelligence by the Indian government with the announcement that a National Centre on AI will soon be set up. This centre will presumably work in close coordination with Centres of Research Excellence in Artificial Intelligence (COREs) that were first proposed by the NITI Aayog in its discussion paper: National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence. While the NITI Aayog identified five areas primed for AI intervention, namely healthcare, agriculture, education, smart cities and smart mobility, the Union Budget speech hints that four more priority areas have been identified.

In a manner now idiosyncratic of the Modi government, the Minister of Finance also announced plans for the creation of an ‘national AI portal.’ Details of what this portal will achieve or what it will be meant for remain unclear. Also missing from the budget are critical details around the quantum of investment in AI and automation technologies that are being planned.

Conspicuously missing from the budget are any references to digital payments or cyber security — both strong protagonists in Modi’s Digital India.

The Finance Minister’s speech also revealed ambitious plans to digitise one lakh villages over the next five years as a part of the Digital India programme by providing WiFi access to these villages. This initiative will be spearheaded by the Common Service Centres that now serve as nodal points of delivery for public utility services.

Conspicuously missing from the budget though are any references to digital payments or cyber security — both strong protagonists in Modi’s Digital India. This absence will likely be felt by Indian tech companies who for a few years now have been demanding economic relief for domestic players to level the playing field and compete with the seemingly limitless cash inflow that US and Chinese tech startups seem to be riding on.

Indian defence

While the defence budget has been pegged at INR 3.05 lakh crore, an increase in absolute terms, the percentage of the GDP used for India’s defence for the year 2019-2020 remains at the measly 1.5% mark, still very low for any effective modernisation to take place. The interim finance minister, in his budget speech, has stated that the current defence personnel will see a rise in the Military Service Pay (MSP), while at the same time allocating funds for special allowances of Air Force and naval personnel who are stationed in high-risk zones. Apart from this funding of the military, the government has also earmarked a separate INR 35,000 crore as part of its OROP pension payments, in line with the BJP election manifesto. However, this defence budget still does not take into account the modernisation needs of the country, pegging only INR 1.08 lakh crore for new weapon systems, while the day-to-day expenses have been given a budget of INR 2.10 lakh crore.

This budget, while being touted as the largest increase in the defence budget of India, still reveals the fact that the Indian military is not being given enough room to upgrade its current equipment to keep pace with the rapid modernisation of the Chinese military. The budget highlights the fact that the government is only willing to keep its military functioning at the level it already is, not taking into account the asymmetry between itself and its neighbours in terms of both technology and equipment possessed. While there is no doubt that this year’s budget is a step forward in the right direction with more money being pooled in the upkeep of the military, serious attention needs to be paid to the slow speeds of modernisation of the military’s resources, which will prove to be a major factor in the coming years, in a time where the Chinese have begun downsizing and modernising and indigenising their equipment to meet the new threats of both the present and the future.

This budget, while being touted as the largest increase in the defence budget of India, still reveals the fact that the Indian military is not being given enough room to upgrade its current equipment to keep pace with the rapid modernisation of the Chinese military.

Towards economic diplomacy

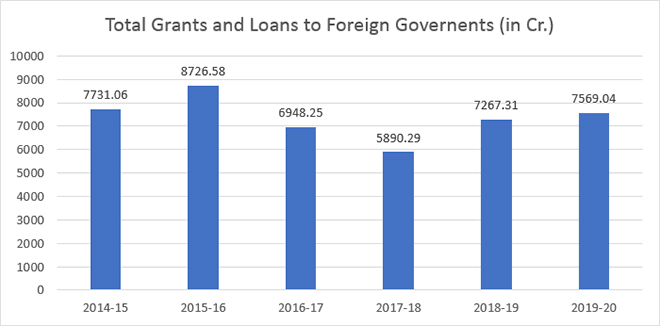

Compared to an allocation of INR 12,620 crore in 2014-15, the overall grant to the MEA in 2018-19 is INR 16,061 crore.

India’s allocation towards economic diplomacy has steadily crossed the USD 1 billion mark.With India already contributing nearly 15% to global growth, it must interrogate the consequences of its development partnerships more closely as allocations rise over the next decade.

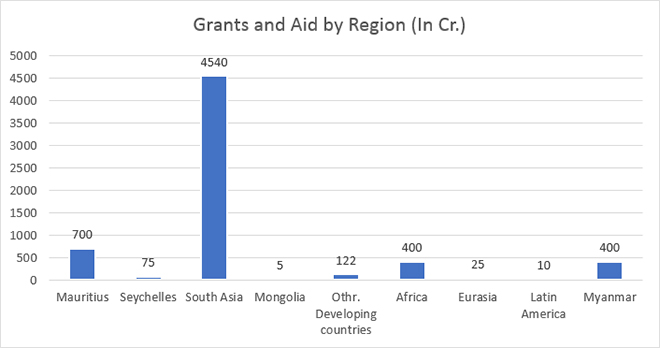

Two notable heads this year are aid to the Maldives and the Chabahar port. Following the establishment of a friendlier government in Male, India has more than quintupled its aid to Maldives — from INR 109 crore in 2018-19 in the original estimate, to INR 440 crore in the revised 2018-19 estimate, and to INR 575 crore this year. And continuing a new practice from last year, India has allocated INR 150 crore for the development of the Chabahar port.

These investments reveal India’s crucial connections to both the Indo-Pacific and the Eurasian landmass. However, while South Asian states receive the bulk of India’s economic assistance, India’s aid to Eurasia stands at INR 25 crore this year.

India’s investments in regional institutions also remains unfortunately low: INR 8 crore each for the SAARC and BIMSTEC Secretariat. While the BIMSTEC budget has doubled over the past two years, it remains insufficient to create effective human or technical capacity in the institution.

Over all, the 2019-20 Budget makes clear that India must recalibrate its approach to economic diplomacy in the region, especially given its domestic constraints.

For one thing, India must begin to identify priority sectors and States — especially in the Indo-Pacific and Eurasia. Development projects that create social and economic value for local communities and where India has a comparative advantage will be key. Supporting institutions like BIMSTEC and the IORA will also be important.