Monthly Archives: October 2021

Building Back Better together—Potential for an India-UK partnership for a Green Transition

This article was co-authored by Terri Chapman

While many have pinned their hopes on technology to solve the looming challenges posed by climate change, it is clear that this alone may not be the silver bullet, and other processes will have to be invested into. For example, one of the most ambitious technological efforts to date is the Climeworks Orca plant that was launched in Iceland last month. The plant is illustrative of the inadequacy of the hunt for the technology elixir. The plant can remove 4,000 tons of CO2 a year, which is equivalent to the annual emission from just 800 cars. To scale this up and make it accessible to different geographies is the hurdle for such innovation. The timelines to do this are incompatible with the urgency of responding to global warming.

It is time to do what we have known needs to be done for decades—which is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These reductions are complicated by the fact that industrialisation is still underway in much of the world. Countries in the global South rightly seek space to grow. However, the template for that development—backed and funded by international financial institutions—is heavily reliant on high-emitting activities with only limited finance being deployed towards cleaner and greener options. At the same time, countries of the global North are dragging their feet and, in some cases, still peddling the idea that climate change can be responded to without dramatic changes in consumption patterns or significant financial reconfiguration. The “blah, blah, blah,” approach to climate change described by Greta Thunberg, is as she says, not working. Instead, countries around the world, especially high-income countries, must realise that they cannot negotiate or talk their way out of the climate mess created by them. Instead, it is time to get their political approach right and to deploy the largest quantum of financial resources ever mobilised to enable equitable green transitions. And there is another complication; this climate war chest will have to be invested into developing countries, which challenges the credit risks and cost of capital logic that have defined the post-War financial flows.

Countries of the global North are dragging their feet and, in some cases, still peddling the idea that climate change can be responded to without dramatic changes in consumption patterns or significant financial reconfiguration.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created renewed opportunities and invigorated the demand to make our cities healthier, make our social protection systems more robust, make our societies more equitable, and to respond to climate change meaningfully. More people now get what “systemic risk” means and the devastation caused by the pandemic should make governments more eager to address such risks.

The United Kingdom (UK) and India are well placed to respond to these new opportunities as partners and to craft a road map together for Glasgow and beyond. This is a partnership with much merit. The leadership for green transitions is coming from countries like India (the only G-20 country living up to its ‘2 degree’ commitments made at Paris) even as control over capital and technology resides in developed countries like the UK. Leveraging their specific roles and strengths, the UK and India can work together as partners in three areas in particular. These include human capital development, climate finance and funding of clean energy and infrastructure, and green and smart manufacturing.

Partnership in higher education

The UK is a global leader in education, knowledge, innovation, and research, while India is one of the largest consumers of higher education and is a market for research and innovation. Higher education enrollment, for example, has tripled over the last 20 years in India but remains at just 28 percent. The opportunity is defined by a simple fact—nearly half of India’s population is below the age of 25 and that demand for higher education is likely to increase. As a result, there is significant demand for UK education opportunities in India. In 2019, more than 37,500 Tier 4 student visas were given to Indian students studying in the UK. While this is a large number of students, in the larger context, it is insignificant and amounts to very little beyond building and nourishing an Oxbridge community in India.

Efforts under the new policy could create greater access to high-quality higher education in India, deepen UK–India academic and scientific collaborations, and create new research initiatives and more significant innovation.

India’s New Education Policy 2020 makes it easier and more attractive for foreign universities to establish branch campuses in India. Efforts under the new policy could create greater access to high-quality higher education in India, deepen UK–India academic and scientific collaborations, and create new research initiatives and more significant innovation. All of these can support broader efforts to foster human capital, skills, and knowledge in India, which are needed to transition towards a more sustainable, knowledge-based economy. UK institutions must re-calibrate their global role by investing in overseas markets and partnering to build the campuses of the future in the geographies that matter. Human capital and research efforts in India will enable innovation and work forces, which will be deployed at the frontlines of global climate and development efforts.

Partnership in finance

The second area of potential for the UK–India partnership is finance. Mitigating climate change will require enormous financial investments. This is much larger than the US $100 billion annual commitment made by the Annex II countries. For example, just for meeting its renewable energy targets by 2030, India will require around US $2.5 trillion dollars. The common but differentiated responsibility for financing green transitions posits that industrialised countries must contribute to (small amounts) and help catalyse large financial flows towards this ambition of New Delhi. However, many are falling behind even on their abysmally small commitments. Unless these trillions of dollars can flow to India and other developing countries, we will lose the climate battle and what unfolds will be unpredictable and consequential.

There are significant and unrealised opportunities for investment in ‘green transitions’ more broadly and at retail scale. Unfortunately, financial institutions are only modest actors in the green spaces in India. Transformative interventions at scale will require new thinking, innovative financial products and more favourable borrowing terms. It will be a crime against humanity if the country with the largest potential to curtail future emissions borrows money from the developed world at exorbitant rates. If Climate Risk is seen as a clear and present danger, cost of funding for climate mitigation projects must remain the same across continents.

Transformative interventions at scale will require new thinking, innovative financial products and more favourable borrowing terms.

The Indian Railway Finance Corporation (IRFC) issuance of climate bonds in 2017 is illustrative of the potential. The bond raised US $500 million from investors around the world. Municipal bodies in India, including the Indore Municipal Corporation (IMC), are also considering raising ‘green masala bonds’ to fund climate responsive projects. Green bonds offer an opportunity for countries like India to access new pools of international funding for green projects, for which there appears to be demand in the UK. In September, the UK issued its first sovereign green bond, raising 10 billion GBP, with demand of nearly 90 billion GBP, indicating the magnitude of appetite for such investments.

Additionally, regulations and perverse laws will have to make way and allow pension and insurance funds to invest into emerging economies that are the ground zero of the climate battle. These funds hold the largest global savings, mostly derived from fossil fuel age businesses and there is justice in their being the patient capital that is deployed in building clean and green infrastructure in emerging and developing economies. Retail finance needs innovation too. Buying a solar facility for rooftops in any market must be at a discount (financial costs) to the credit available for purchase of cars and air-conditioners. Bulk finance and retail finance have not yet signed the Paris Agreement; can London and New Delhi partner to change this?

Partnership in green manufacturing and value chains

The third opportunity is around supporting green and smart manufacturing and green value chains. Again, the pandemic has revealed the risks of over-dependence on any single country to supply critical goods. China, for example, owns the largest solar and wind manufacturing companies. India offers an alternative and an opportunity to diversify supply chains and make them more resilient. This is a chance to invest in and build up India’s smart and green manufacturing capabilities and create more robust supply chains for renewables and other green technologies. The R&D and innovation out of the UK has recently served only Beijing. It is time to rethink this monochromatic value chain. An India and UK innovation and smart manufacturing bridge is needed. The potential of such collaboration is illustrated by the AstraZeneca vaccine, for which R&D took place in the UK, with mass manufacturing in India at the Serum Institute of India – the world’s largest vaccine producer. India is also ramping up its green production and manufacturing capabilities in areas such as hydrogen production and the manufacturing of next generation battery technologies to support green transitions. Indian companies are scouting for partnerships; and it is time to put some political weight behind it. The Build Back Better World and the Quad and the EU and India partnership all support this.

India is also ramping up its green production and manufacturing capabilities in areas such as hydrogen production and the manufacturing of next generation battery technologies to support green transitions.

We must act to save lives, improve health, protect livelihoods, and safeguard resources for current and future generations. But the single most important motivation has to be the collective will to improve the lives of billions who have been excluded from the economic mainstream and, indeed, from any access to dignity and livelihoods. These constitute the largest cohort on the planet and their continued misery must not underwrite the green-tinted splurges of the rich world. The UK and India are in a position not just to act but to act as partners to change this.

The supply of COVID-19 vaccines has improved, but has demand for it saturated in India?

This article was co-authored with Oommen C. Kurian

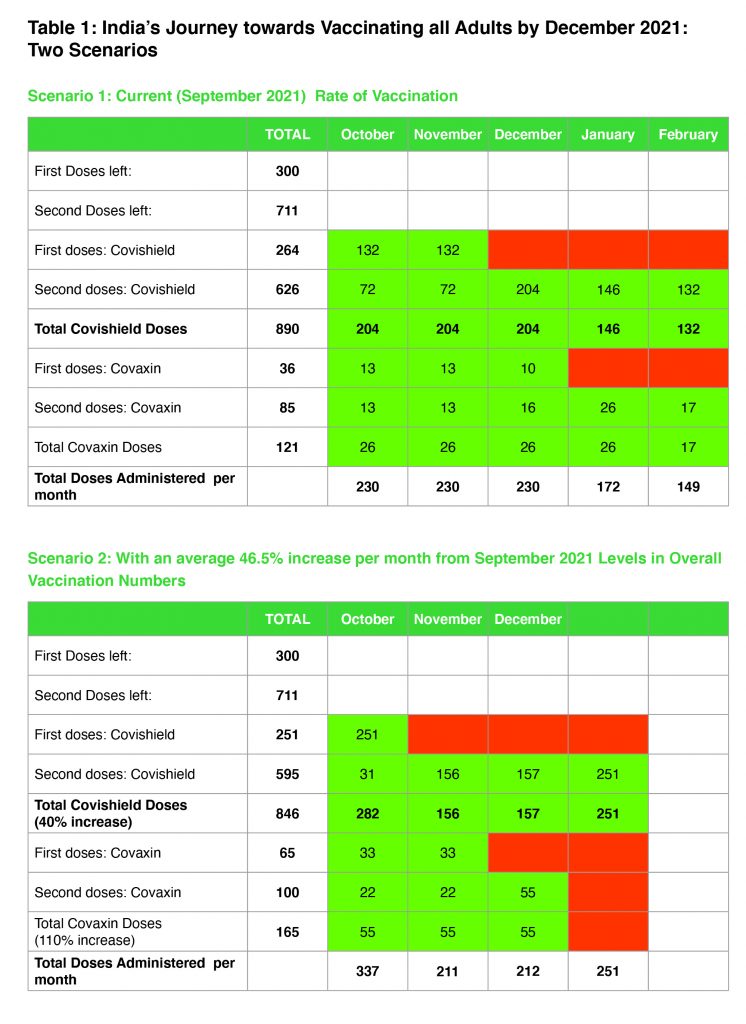

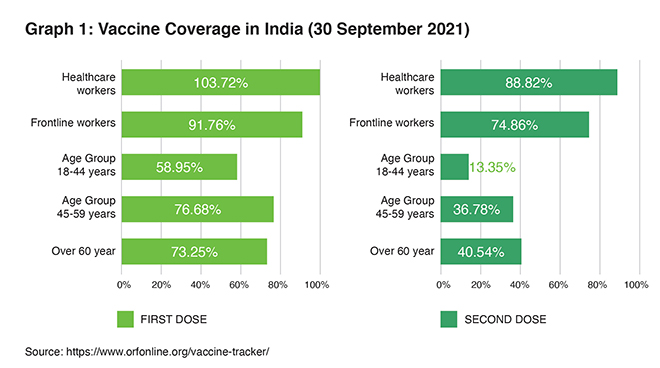

Latest available data indicates that India has administered 699.6 million first doses and 286.3 million second doses of COVID-19 vaccines to its adult population. The coverage is markedly higher amongst the 45+ population (Graph 1), with about 80 percent within the age group having received at least one dose, and more than 40 percent fully vaccinated. The Government of India’s goal is to vaccinate all adults against COVID-19 by 31 December 2021, and therefore, the pace of vaccination in the last quarter is of importance.

Graph 1: Vaccination Coverage Across Age and Occupational Categories

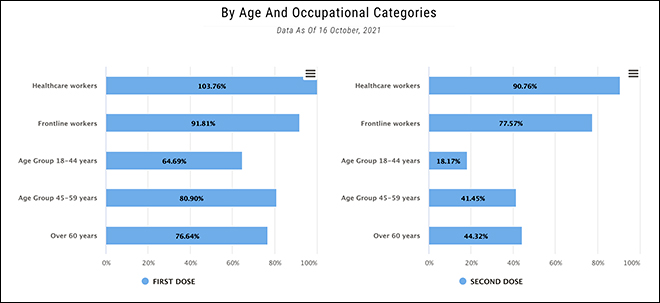

The numbers in the recent weeks have been disappointing. Instead of accelerating to the required average daily vaccination rate of more than 11 million per day (required on October 1), the number of daily vaccine doses administered has shown a stagnation and, indeed, a decline. From 8.2 million doses on 8 October, the daily numbers have declined considerably, taking down the seven-day moving average from 6 million per day to 3.9 million per day on 18 October. While the festivities across the country may be part of the explanation, there are clearly other factors at play, which may undermine the 31 December target that the Government of India has set for itself. This, therefore, needs to be explored in-depth; the possible reasons behind such a surprising slowdown in the vaccine uptake uncovered and remedial measures instituted need to be examined.

Graph 2: Number of Vaccine Doses Administered per Day

Is the decline in numbers due to supply constraints?

While it is a legitimate question to ask, given the history of delays in capacity ramp up for different vaccines in India, this does not seem to be the driver of the slowdown. A look at the unutilised vaccine doses still available within the vaccine cold-chain—the difference between doses supplied to the states and those administered—strongly points to this. A weekly analysis of the available doses with the states (Graph 3) shows that there is substantial build-up of vaccine inventory at the state level. During a month between 15 September and 14 October, the doses available with states almost doubled from 46.3 million to 88.9 million. The data made available on 18 October indicates that there are currently 107.2 million doses awaiting to be administered at the states and union territories. This trend indicates one possibility: There is a strong tapering off of demand for COVID-19 vaccines.

Earlier this year, at the beginning of the vaccination drive, when both number of cases and deaths were low, there was a distinct lack of demand for vaccines, which shot up only with the surge in cases. However, with more than 70 percent adult Indians already vaccinated with one dose, this may not be the major contributor. Demand may be flagging as many Indian states may have already reached almost all of the “willing” adults with one dose at least. Perhaps the undecided and the ‘vaccine hesitants’ are now the ones left and the tapering of numbers could be an outcome of this.

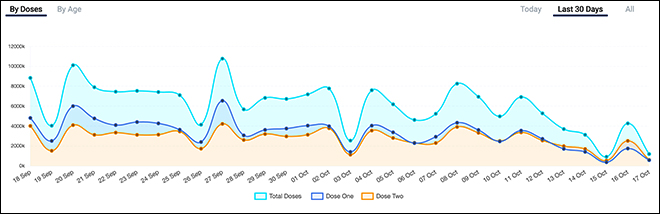

Graph 3: Weekly Analysis of Doses Available in the State-level Cold Chains

Weekly vaccination data disaggregated by doses from the 1st of September onwards (Graph 4) underlines this possibility. As a proportion of the weekly doses, first doses are on a clear decline over the last six weeks. In the first week of September, first doses constituted almost 70 percent of total vaccinations, but in the second week of October, it was just over 50 percent. This could only mean that the vaccination drive in many parts of the country may have already reached the easy-to-reach population. Vaccinating all of the remaining 30 percent or so of adult Indians will require additional efforts from the government, local leaders, and civil society.

Graph 4: Proportion of Weekly First and Second Doses

Towards herd immunity: the last mile will be the hardest

In the third week of October so far, second doses have outstripped first doses by a big margin. Between 14th and 18th October, of the total 14.8 million doses administered in India, only 6.3 million were (42 percent) first doses, showing clearly that the second doses are now driving the overall numbers. With the offer of free vaccine for all adult citizens, the Government of India has removed financial access barriers from the picture. However, for many sub-populations, physical access to vaccination centres may be difficult for a range of reasons. Vaccine hesitancy will also be a problem in a small but significant proportion of the population. To overcome these, the government must run the vaccination drive in surgical mode, focusing on communication, community engagement and hard-to-reach populations. Many states are already deploying mobile vaccination teams to take vaccines to the people in the margins, with success.

At the same time, the centre and state governments must now focus on district-level champions to win the battle of perception, and to take vaccines to the constituency that is the most difficult to reach—those hesitant to take vaccines. That many of them may be highly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to age or comorbidities makes such an initiative an ethical imperative. In short, first doses are drying up across the country, which could be either due to access-related issues or vaccine hesitancy. India needs district level mop-up operations. The vaccination drive’s initial phases leveraged technology in a big way, but the last mile needs to leverage communities and personalities alongside technology. Many countries are finding ways to nudge and even push the citizenry towards COVID-19 vaccination, focusing on employers and travellers. Canada, for example, is planning to place unvaccinated government employees on unpaid leave and has also made COVID-19 shots mandatory for air, train, and ship passengers.

The vaccination drive’s initial phases leveraged technology in a big way, but the last mile needs to leverage communities and personalities alongside technology. Many countries are finding ways to nudge and even push the citizenry towards COVID-19 vaccination, focusing on employers and travellers. Canada, for example, is planning to place unvaccinated government employees on unpaid leave and has also made COVID-19 shots mandatory for air, train, and ship passengers.

Throughout the pandemic, India has had one of the highest proportions of population willing to be vaccinated when compared with other countries. For the same reason, a smart communication campaign should do in India what vaccine mandates are failing to do in many other countries. With almost 100 crore vaccine doses administered, and a robust information backbone tracking tests, vaccinations and cases, it should not be difficult to convince those still doubtful about the efficacy or the safety of vaccines. Popular personalities, political and religious leaders, and civil society organisations should be engaged actively to take evidence-based messaging to the district level, particularly in those areas where vaccine uptake remains low. Given the deceleration in vaccination we observed over the last few days, it is easy for India to be in a situation where vaccine doses to meet the 31 December target are available but demand becomes the binding constraint.

The next 90 days: India’s ambitious attempt to vaccinate all adults

This article was co-authored by Oommen C. Kurian

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious decision and the Government’s announcement to vaccinate all adults against COVID-19 by 31 December 2021 is now within reach. At the time of its announcement, the vaccination plan was seen to be both implausible and impossible by many who doubted India’s capacity and capability in dealing with this gigantic task. Some were also skeptical of the Indian State’s capacity to deliver the doses to a very diverse demography across the country. With the quick evolution of the CoWin platform, India has surmounted the challenge of having a reliable vaccination management solution at scale with the capability of working online and offline while providing a verifiable database. With the vaccine run rate of September where India delivered over 230 million doses, and assuming a modest increase in vaccine availability for the remainder of the year—relative to the significant buildup in the past five months—India has shown that it may just be able to dispense close to 1900 million doses by the end of this year.

Almost three-fourths of the elderly population in India has already gotten at least one dose, and the coverage in the 45-59 age group was even higher. Overall, more than one-third of the 45+ aged citizens in India are fully vaccinated.

It is now widely acknowledged among experts that the national vaccination drive is doing well when compared with other lower middle-income countries, and even some middle-income countries. At the end of September, India had managed to administer around 890 million doses among adult citizens. According to government communication at the end of September, more than 45.7 million vaccine doses are still available in stocks with States/UTs, with under 8.4 million doses in the pipeline. Almost three-fourths of the elderly population in India has already gotten at least one dose, and the coverage in the 45-59 age group was even higher. Overall, more than one-third of the 45+ aged citizens in India are fully vaccinated (Graph 1).

Graph 1: Vaccine Coverage in India (30 September 2021)

This is an admirable and astonishing achievement by a lower middle-income country and a feat that, for obvious reasons of scale and size, will have no parallel in the free world. Even as we are within a whisker of meeting the (self-imposed) deadline in terms of number of vaccine doses that we need for the task, some policy posers stare back at us and need to be addressed now to complete the job. And this must be an imperative.

In the recent past, we have witnessed that countries confronted with new waves of the pandemic have had two distinct characteristics; the relatively richer countries are seeing waves that are moderate while the poorer countries in general are experiencing their peak surges. This also typifies the global “Vaccine Divide”. The US represents a starkly unique geography where we have seen both play out simultaneously. The vaccine divide in the US is shaped more by political and ideological factors with deleterious consequences.

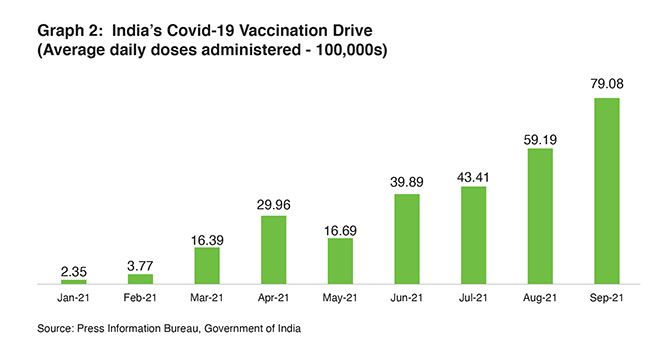

From the early days of the Liberalised Pricing and Accelerated National COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy in May, when the daily vaccine doses administered were around 2 million, India’s vaccination drive has come a long way with the month of September witnessing an average of over 7.5 million doses a day.

Experts have observed a general “decoupling” within the pandemic landscape, where countries and communities with access to vaccines are able to separate the intensity of transmission (case numbers) and the adverse outcomes such as severe disease, hospitalisation and death. Many nations with a high number of vaccinated people are now beginning to approach SARS-CoV-2 like an endemic virus. However, while there has been a general lowering of cases and adverse outcomes these past days, it would be dangerous to believe that we are at the tail of the pandemic. Mutations and large swathes of unvaccinated people offer the virus a chance to continue to be lethal and for the pandemic to take a dangerous turn. Vaccinating all adults and teenagers still has to be a national priority.

From the early days of the Liberalised Pricing and Accelerated National COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy in May, when the daily vaccine doses administered were around 2 million, India’s vaccination drive has come a long way with the month of September witnessing an average of over 7.5 million doses a day. An analysis of monthly vaccination numbers from the start of the vaccination drive (Graph 2) reveals a substantial scale up. While 61 million doses were administered in May, September saw over 230 million doses being administered, indicating an impressive quantum of capacity buildup of nearly 400 percent.

Graph 2: India’s Covid-19 Vaccination Drive (Average daily doses administered – 100,000s)

India set itself an ambitious aim of inoculating all its adult population by the end of 2021. That means, in real terms, giving two doses of vaccines to around 950 million people—delivering, in all, 1.9 billion doses. As on the end of September, India had managed to administer a total of 889 million of those doses, with 650 million being first doses and 239 being second doses.

Over the remaining days in this year, India needs to deliver over a billion doses and deliver them as per the dosage cycles of the two main vaccines—Covishield and Covaxin—currently dominating the vaccination drive. This would mean India now has to achieve the next quantum leap and achieve more than 11 million doses a day on average, which is a ramp up of 46.5 percent in the last three months.[1] With more vaccine manufacturing facilities coming online and given the substantial scale-up already achieved by the vaccination drive, it just may be possible, judging from past experience.

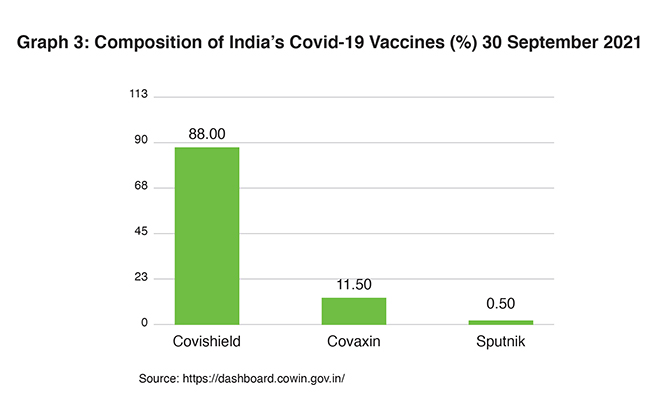

COVID vaccine(s) used and its impact on the speed of the vaccination drive

But the rub lies elsewhere, the mainstay of the Indian vaccine effort is the Serum Institute’s Covishield, which accounts for approximately 88 percent of all doses delivered as of now and has a dosage cycle of 12 weeks (Graph 3). As of October 1st, there were nearly 300 million adults who were yet to receive the first dose. Some of them can be vaccinated with Covaxin or Sputnik-V (both have a dosage cycle of one month or below) while a substantial number of them will have to spill over into January if the Covishield dosage cycle of 12 weeks is to be followed.

The policy poser, therefore, may not just be about a vaccine capacity ramp up of about 47 percent, which is eminently doable, but the composition of the vaccine candidates given the dosage gap.

India needs to deliver over a billion doses and deliver them as per the dosage cycles of the two main vaccines—Covishield and Covaxin—currently dominating the vaccination drive. This would mean India now has to achieve the next quantum leap and achieve more than 11 million doses a day on average, which is a ramp up of 46.5 percent in the last three months.

There are three hypothetical responses that can be considered by the health ministry. First, is there a genuine possibility of Covaxin finally ramping up its production and stepping up to the plate? Even if they were able to double their production, we will still have a large, uncovered population unless Sputnik V exponentially increases its production. The second option is to reduce the gap between two doses of Covishield. This will allow the bulk of the vaccine capacity to be used for second doses in much of November and all of December. And the third, of course, is that a new vaccine with large capacity (doses) and shorter dose gap enters the scenario latest by October end.

In a situation of major delays in the scale-up of all the other candidates, it is Serum Institute’s “over performance” in Covishield production, going beyond even the most optimistic projection five months back, that has helped India’s vaccination drive.

Of the other major vaccines that will be available in India soon, application for emergency use authorisation of Covovax is likely to be made only by the end of 2021, according to Serum Institute and, thus, it is unlikely to make a big difference in the timeline we analyse here. Similarly, reports indicate that a surge in cases in Russia will affect Sputnik-V’s plans in India, although the vaccine with a short 21-day dosage gap would be ideal, given the tight timelines. Biological-E’s production of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine will likely take off only by the end of the year, and no information on timelines is currently available. Zyduc Cadila’s three dose vaccine is also bound to start production at a modest rate of 10 million doses a month; and as the first vaccine approved in India for use in children, it may not make a difference in the adult vaccination numbers at least in 2021. Although Zydus Cadila’s doses can be available for the adult vaccination drive, as the only vaccine yet approved for children, the initial doses should go to children with co-morbidities.

Covaxin is reportedly expanding production from 35 to 55 million doses from October onwards. The Government of India has also clarified that, for now, there is no plan to reduce the mandatory three-month wait for second shots of Covishield. However, with more doses being available for the national vaccination drive, this may be revisited.

Possible pathways for India’s vaccination drive

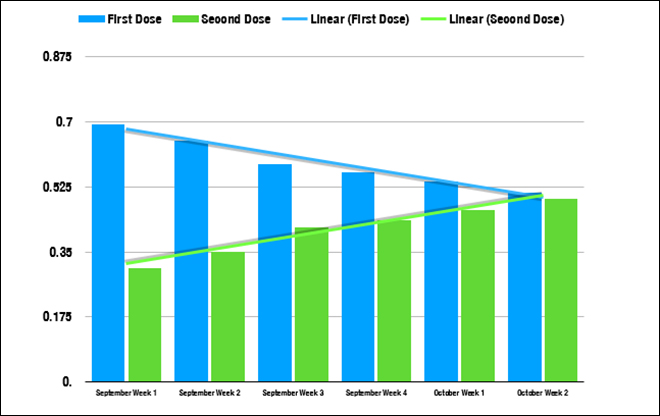

The following exercise discusses two possible scenarios among a cluster of pathways that are likely to emerge in the coming months that would allow India to fully vaccinate its adult population

(Table 1). Available information till date suggests that there are three factors influencing the December deadline of the immunisation drive, namely, manufacturing capacity which is fast improving; the three-month gap between Covishield doses; as well as the need to have an exportable surplus. Scenario 1 assumes that the availability of vaccines will remain at the September 2021 levels, which is around 230 million per month. In such a scenario, it will be possible to vaccinate all adults in India only by February 2022 and at the end of December, India will be 321 million doses short (Table 1).

Scenario 2 assumes an average 46.5 percent increase in the vaccine doses compared to the September 2021 levels. Given that between May and September, daily vaccine doses administered increased by 400 percent, such an increase is not impossible. After Covishield recently announced that its production capacity has been ramped up from 160 million doses a month to 200 million doses, reports already suggest that that the company will be delivering 220 million doses in October, indicating an accelerated scale-up like in the previous months. In Scenario 2, India will vaccinate every adult with one dose in December 2021, and with both doses in January 2022, with 251 million second doses of Covishield spilling over to January 2022.

These scenarios ignore Sputnik-V as the surge in cases in Russia is holding up imports of vaccine components. Indeed, India has not made vaccination mandatory, and a considerable proportion of the adult population will be reluctant to take the jab voluntarily, for a range of reasons. Our analysis assumes that any Indian citizen above 18 years of age should be able to demand and receive two vaccine shots within the timeline. Thus, it does not discount for vaccine hesitancy and considers every eligible individual in the analysis. This analysis also does not consider possible innovations in the future like fractionation of COVID-19 vaccine doses among the relatively less vulnerable population or mixing of vaccines (something we already do within other disease control programmes in India), which can extend limited supplies, reduce mortality and also accelerate the journey towards universal vaccine coverage.

Table 1: India’s Journey towards Vaccinating all Adults by December 2021: Two Scenarios

As is clear from the numbers, in light of the global context, scenario 2 seems feasible, whereby all adults are covered with at least one vaccine dose by the end of November 2021, and their respective second doses spill over into 2022. For a country of 950 million people over 18 years, securing universal coverage of a single dose in 11 months will itself be a commendable achievement. Scenario 2 also accounts for considerable exportable surplus of vaccine doses from November 2021.

Even as India accelerates its vaccination process among adults, unfortunately, there is no such thing as herd immunity threshold exclusively for the adult population. Herd immunity for COVID-19 will have to be achieved at the overall population level, and for a very young India, this means a need for a substantial number of its under-18 population to be vaccinated. Even if India manages to inoculate all its willing adult population by December 2021 or even January 2022, unless its hundreds of millions of children are vaccinated, the country cannot reach anywhere close to herd immunity levels. Achieving that, while respecting renewed commitments to export vaccines to the rest of the world, will be the next ambitious goal for India as the country tries to turn COVID-19 into a manageable risk, controlled by access to vaccination and responsible behaviour.

This exercise proves that the goal of vaccinating all adults by 31st December 2021 is not as unrealistic as it may have seemed earlier. As India continues to steadily ramp up Covishield and Covaxin production as it has in the past, it can achieve the ambitious tasks of vaccinating all adults by January 2022, sharing doses with the world, and to also consider provision of booster doses to severely immunocompromised citizens.

[1] Based on calculations done by the authors using the statistic that between May and September, daily vaccine doses administered increased by 400 percent