by Samir Saran and Vivan Sharan

March 12th, 2011

Please find here the original article

the original article

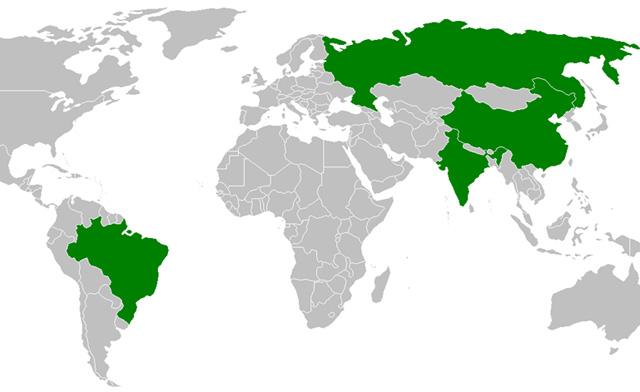

The 4th BRICS Academic Forum recently concluded in New Delhi. Over 60 delegates representing academic institutions, think tanks and expert community from the member countries participated in substantial debates that covered virtually every challenge and opportunity of contemporary times. The debates were intense, sometimes combative but almost always conducted among friends. This was the key takeaway from this meeting. The community is strong, it is aware of the differences, eager to resolve those and is comfortable with the irresolvables. The skeptics of BRICS for four years, would now need to rethink, this group has evolved, this group sees potential in greater and deeper engagement, and this group is capable of proposing bold and visionary ideas at the New Delhi Summit later this month and in the other interactions before and after.

This was not always the case and we only have to recall the early days of the relationship. To anyone witnessing one of the early Track 2 interactions on a cold day in Moscow in 2008, it would have seemed improbable that the grouping would come this far. There was early hesitance and unformed agendas among each of the experts gathered from the four countries (at that time BRIC). The Brazilian experts were unsure of their being there in the first place. A very prominent diplomat from Brazil saying, “why are we here, why do you need us, you are all neighbours and should talk amongst yourselves”. The Russians at that time, and who must be credited for the inception of the BRIC idea, saw in it a political opportunity to create a grouping of that could counter the Atlantic alliance and the Western economic and political weight. They were to be dissappointed, India and China were already deeply integrated with the US and EU in the arena of trade and economics and would not play ball. The experts from China liked the BRIC idea, which could be another instrument for projecting their growing pole position in world affairs and India was beginning to manage the nuances of diverse relationships in multi-polar world. It had also learnt from the SCO experience and this time it would not demur.

However, the early days of the conversations amongst experts and indeed among the policy makers from these countries lacked detail. This has changed, from the macro discussions on global governance, financial architecture, security and greater coordination, the discussions today focus on the substantive, on experince sharing, on creating institutions and linking up existing ones. In the fourth year of the BRICS (South Africa joined last year), the group has come of age. This is attested to by two facts. First, the experts from the four countries have signed an agreement to step up their interactions which till now have been sporadic and on the sidelines of the Leaders Summit and two, the wide ranging recommendations that the experts forum has submitted for the consideration of the Leaders at the summit in New Delhi demonstrate the limitless possibilities for the grouping.

The Forum’s recommendations to the 4th BRICS Leaders Summit to be held in New Delhi on March 29th are relevant and actionable. They are the result of intense discussions, debates and negotiations between the delegates on common challenges and opportunities faced by BRICS members, as they seek to set the global agendas for governance and development going forward. The theme for this year’s Academic Forum was “Stability, Security and Growth” – all common imperatives for the emerging and developing BRICS nations.

17 policy recommendations were carefully crafted by the Forum and are centred on key priorities for BRICS within the aegis of governance, socio-economic development, security and growth. The mandate of the Forum was to provide concrete policy alternatives to BRICS Leaders and to the credit of the delegates this year, the recommendations may have lived up to the mandate. The Forum deliberated context specific micro debates embedded within larger narratives. Varied and significant themes were addressed including the articulation of a common vision for the future; a framework to respond to regional and global crises; climate change and sustainable resource use; urbanization and its associated challenges; improving access to healthcare at all levels; scaling up and implementing new education and skilling initiatives; the conceptualization of financial mechanisms to support and drive economic growth; and finally sharing technologies, innovations and improving the cooperation across industrial sectors and geographies.

The Forum deliberated upon two distinct sets of engagement. One set of engagements is through research and initiatives that are “Intra-BRICS” in nature. These involve experience sharing across social policy, resource efficiency, poverty alleviation programmes, sustainable development ideas, innovation and growth. Each of these themes can be effectively mapped to help tailor policy within BRICS. The recommendations highlight the possibilities for enhancing such engagements through exchange of institutional experiences and processes, free flow of scholars and students, joint policy research, capacity and capability building for facilitating such interactions.

The second set of engagements and outcomes pertain to interaction of BRICS with other nations, external actors and groupings at various multi-lateral forums and institutions. These are reflected in the recommendations pertaining to climate policies, Rio +20, financial crisis management, traditional security threats, terrorism and other new threats and global challenges around health, IPR and development.

The Forum provided a valuable platform for exchange of perspectives between delegates without adhering to national positions or party loyalties. There were heated debates on issues such as the possible institutionalisation of a BRICS Development Bank and an Infrastructure Investment Fund that could assist in the development aspirations of the BRICS and other developing countries. The discussions on the setting up on new, credible institutions to initially supplement and eventually substitute existing financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF reflect the strong desire of BRICS to move ahead and away from the traditional development agendas of 20th century institutions that are today incapable of empathising with some of the realities and aspirations of the 21st century. This is perhaps a reflection on the way Bretton Woods Institutions are managed and governed and indeed to their legitimacy itself.

The recommendations reveal that BRICS view the sustainable development agenda through the lens of inclusive growth and equitable development primarily. The recommendations have also clarified that BRICS will continue to focus on achieving efficiency gains in resource use. Both these outcomes point towards resolute and far sighted policy guidance by the Forum. Climate change mitigation debates which have become a proxy for “Promoting Green Technology” and indeed are an outcome of “re-industrialisation policy” of some EU countries were conspicuous by their absence from the debates. Instead, with “plurality in prosperity” as a common ideal, the outcomes also signify that the research community within BRICS want the sustainability discourse to shift from one that emphasises common responsibility to one that emphasises common prosperity. This means that BRICS must attempt to reorient consumption patterns and energy use globally, towards sustainable trajectories. The BRICS Leaders would do well to replicate the cohesiveness of the BRICS academics in the articulation of their vision for creating sustainable economies, ecologies and societies. Similarly the promotion of cultural cooperation, establishing innovation linkages, sharing pathways to universal healthcare and medicine for all, strenghthening indigenous knowledge are all recommendations that are timely and appropriate.

The gradual transition process of BRICS becoming the global agenda setters has been one of the more exciting developments to watch and study. While sceptics may still dismiss the possibility of BRICS being “rule-makers”, it is unlikely that they will not influence “rule-making” processes. The experts at the forum were unambiguous in their vision for the grouping. While recognising that in many instances BRICS might eventually yield to sub optimal policy formulations due to national agendas and geo-political constraints, they were determined that the incubation period is over and now the bar must always be set high and the leaders must be ambitious. In the words of one of the delegates at the 4th BRICS Academic Forum, BRICS have indeed created a “new geography of cooperation” and opportunities are boundless.

Samir Saran is Vice-President and Vivan Sharan an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation. The foundation hosted the 4th BRICS Academic Forum.