Category Archives: Uncategorized

Samir Saran: “India no quiere verse atrapada entre el binario Estados Unidos-China”

El analista indio analiza en conversación con EL MUNDO la situación geopolítica actual, el impacto del auge de Pekín en el Indo-Pacífico y la estrecha relación de India con Rusia

Bisagra entre Oriente y Occidente, India es un actor de primer orden en el tablero geopolítico. Es ya el país más poblado del planeta, dispone del tercer mayor presupuesto de defensa, es una potencia nuclear y ha sabido mantener cierto equilibrio en sus alianzas con Moscú y Washington, al tiempo que refuerza su importancia estratégica en el Indo-Pacífico frente al auge de Pekín y estrecha lazos con otros países no alineados del llamado Sur Global.

“Nos vemos como los garantes de la seguridad y la estabilidad en la región; tenemos que ser políticamente firmes para impedir que China socave no sólo la integridad soberana de India, sino también la de nuestros vecinos”. Son palabras de Samir Saran, presidente del Observer Research Foundation (ORF), comisario del Diálogo Raisina y presidente del Consejo del Secretariado Indio del T20, sobre el estado de la seguridad en el Indo-Pacífico, en conversación con EL MUNDO en Madrid, tras participar en una mesa redonda organizada por la Fundación Consejo España-India.

“Las conversaciones”, subraya, “importan ahora más que nunca”. En su calidad de comisario del Diálogo Raisina, Saran afirma que “se ha puesto demasiado de moda ‘cancelarse’ el uno al otro” cuando discrepan distintos actores geopolíticos. Por eso, tal y como advierte el analista, Nueva Delhi no se dejará atrapar entre los binarios del orden mundial actual: “India no está en el bando de nadie”.

El orden mundial actual está marcado por el tira y afloja geopolítico entre Rusia y Occidente, con el telón de fondo de la guerra en Ucrania, la creciente rivalidad sino-estadounidense y el paso del multilateralismo a la multipolaridad. ¿Qué lugar ocupa India en este tablero mundial?

A India no le gustaría ser necesariamente una de las piezas del tablero, sino más bien uno de los artífices de la partida de ajedrez. Nos gustaría ser un país con agencia política, dispuesto a asumir la responsabilidad de ayudar a diseñar y elaborar lo que surja de este periodo de turbulencias geopolíticas que usted ha esbozado, y creo que ésta es la transformación que hemos visto en las últimas décadas. Sin embargo, India es consciente de las realidades a las que todos tenemos que encarar, en concreto el paso del multilateralismo a la multipolaridad. El primero ha funcionado bien cuando ha habido una o dos superpotencias, pero aún está por probar con cinco, seis o incluso siete centros de poder diferentes. Es decir, el multilateralismo aplicado a un mundo cada vez más multipolar es un proyecto aún por emprender. Pero cuando suceda, India quiere ser uno de los países que ayuden a crear esa arquitectura de gobernanza mundial que sea capaz de acomodar esta nueva realidad de multipolaridad.

¿Y cómo se posiciona India en un mundo multipolar?

India no quiere verse atrapada entre los binarios que nos ofrece el orden mundial actual. Queremos poder forjar el camino que mejor nos convenga -que convenga al 16% de la humanidad-, el que nos permita crear un mundo que responda a las necesidades de los millones de jóvenes indios que aspiran a mejorar su calidad de vida. Por eso, considero que India se ha puesto del lado del ‘Equipo India’.

Históricamente, India se ha escudado en una postura de “no alineación” con ningún bloque, siendo ‘la amiga de todos’. ¿Es esto viable hoy?

India no tiene reparos en denunciar las acciones políticas de nadie. Que no estemos alineados no significa que seamos neutrales. El siglo pasado, nuestro país fue miembro fundador del Movimiento de Países No Alineados, que no era algo que se pretendiera valorar como algo estratégico. Se trataba de un colectivo de países que no comprometían su capacidad de decisión en función a los ‘bandos’ a los que pertenecían. Pero hoy sí es estratégico. La “no alineación” de hoy es una postura que no sólo adoptan países individuales, sino también organizaciones internacionales, como la Unión Europea. Si el mundo avanza hacia el binario de Estados Unidos frente a China, Bruselas no quiere estar ni en el bando estadounidense ni en el chino. Quiere hacer negocios con ambos, al igual que India. Y, desde luego, India no pertenece a ningún bando. Se le puede llamar “no alineación”. Se le puede llamar “multi alineación”. Incluso se le puede llamar “alineación estratégica”, pero India no está en el bando de nadie.

¿Cómo interpreta entonces la abstención india en las votaciones del Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU?

Según algunos países, como China y el Reino Unido, al abstenernos en las votaciones del Consejo de Seguridad hemos actuado contra Rusia, pero sin “alinearnos” del todo con Occidente. Pero nuestro voto no es un mensaje a Europa ni a Estados Unidos. Nuestro voto es un mensaje a Rusia: queremos que acabe la guerra.

Pero si India realmente quisiera que acabara la guerra, no se habría abstenido en la votación…

Rusia ha sido históricamente nuestro más firme defensor en el Consejo. Cada vez que se proponía una resolución adversa contra India, los rusos la vetaban. Ahora, para un país que nos ha prestado tanto apoyo en el plano internacional, una abstención india es un voto negativo que les dice que no nos estamos de acuerdo con lo que han hecho. Y pudimos hacerlo porque no pertenecemos al ‘Campo A’ ni al ‘Campo B’. Pero, ¿es esto un reflejo de nuestra relación con Rusia? Por supuesto que no, nuestra relación con Moscú va más allá de este incidente. La gente buena hace cosas terribles, las naciones honradas a veces se comportan como villanos. Pensemos en Estados Unidos en Irak. ¿Cuántos de nuestros amigos estadounidenses votaron en contra? ¿Cuántos se abstuvieron? Tal vez uno. Todos siguieron adelante con la destrucción; siguieron adelante con una clara violación de todos los principios del derecho internacional y de las normas internacionales porque a veces los buenos países tienen un momento de locura. Pero no ‘cancelamos’ a Estados Unidos, no dejamos de hablar con ellos por lo que hicieron. Por eso, hay que entender que nuestra relación con Rusia precede a la guerra. Es mayor que el conflicto.

¿Y la relación con Rusia por el gas?

Cada Estado tiene que cuidar de su pueblo, por eso todos han mantenido relaciones con Moscú en el sector energético. No se puede culpar a los indios por comprar energía a un país al que también se la compran. La energía no es un quid pro quo. La energía no influye en mi voto en la ONU. Es una mercancía que busco. Y, por cierto, hay que dar las gracias a India. Si no compráramos nuestra energía a Rusia, los precios del petróleo se habrían disparado. Hemos hecho un servicio al resto del mundo al poder adquirirlo, refinarlo y devolvérselo para que sus coches funcionen. Al fin y al cabo, los mercados energéticos son eso: mercados. No son acuerdos gubernamentales ni tratados. Se basan en los principios de precio, acceso, demanda y oferta. A eso es a lo que hemos respondido.

India asumió la presidencia del G20 el pasado diciembre bajo el lema ‘El mundo es una sola familia’. Sin embargo, en la reunión de ministros de Asuntos Exteriores celebrada en marzo en Nueva Delhi, el titular indio no logró convencer a EEUU, Rusia y China para que emitieran una declaración conjunta sobre la guerra. ¿A qué retos se enfrenta India en lo que queda de mandato?

El mundo debería alegrarse de que el año pasado fuera Indonesia quien estuviera al frente del G20, y que este año sea India y el siguiente Brasil. Esta troika de países en desarrollo garantizará que el foro no muera. Si alguno de los miembros europeos hubiera estado al mando cuando estalló la guerra, el G20 se habría convertido sin duda en G19, G18 o incluso G17. Así que, si el foro sigue siendo solvente, será algo que estas presidencias, que casualmente están alineadas juntas, habrán conseguido. Por tanto, uno de los principales objetivos es garantizar que el G20 continúe como idea, como grupo, como foro para resolver algunos de los problemas más cruciales que se han visto eclipsados por la invasión rusa de Ucrania. Aunque no hubo una declaración conjunta, lo que sí conseguimos fue una declaración de efectos acordada entre todos los miembros. Pero si queremos ser ambiciosos en la búsqueda de soluciones tangibles sobre el clima, la tecnología y otras cuestiones financieras, tenemos que encontrar una respuesta a los dos párrafos sobre los que no llegamos a un consenso. De lo contrario, tenemos que ser lo suficientemente astutos como para darnos cuenta de que quizá necesitemos idear un nuevo formato para la resolución de conflictos, en el que tengamos un conjunto de tareas acordadas que llevar adelante y una secuencia de análisis divergentes de la situación política actual, que también podamos hacer constar, estemos de acuerdo o no.

Pekín no sólo compite por la hegemonía mundial frente a Washington, sino también por el control del Indo-Pacífico, donde India ha reivindicado su papel como proveedor de seguridad. ¿Qué percepción tiene de China?

Hace tres años, en una entrevista para un periódico indio, dije que China era a la vez un país moderno y medieval, una especie de Reino Medio, por así decirlo. Es moderno porque su patrimonio es fruto del auge de la tecnología, la fabricación y las cadenas de suministro. Sigue creyendo que es el Reino Medio y que el mundo debería girar a su alrededor, pero su mentalidad es medieval. Cree en el control estatal sobre la innovación, las empresas y sus ciudadanos. Y esa seguiría siendo una valoración justa de China hoy, tres años después. No he cambiado de opinión.

¿Es posible el diálogo con China?

China sueña con un mundo en el que sea uno de los principales centros de poder, y el único en Asia y el Indo-Pacífico, un modelo de unipolaridad que India rechaza tajantemente. Hay que impedir que China socave la integridad soberana india, pero no podemos desear que desaparezca. Tenemos que sacar músculo político para hacer frente a sus amenazas. Tenemos que desarrollar una fuerte capacidad militar para impedir que se aventuren en nuestro territorio. Pero, sobre todo, tenemos que mantener un diálogo sensato con Pekín: ha de ser una condición previa para una coexistencia sostenible.

¿Qué importancia tiene la alianza Quad para las relaciones estratégicas de India en el Indo-Pacífico?

Se subestima el impacto de esta alianza. Somos cuatro países muy distintos, cada uno con un planteamiento distinto de la política interior y exterior, pero aun así compartimos la misma valoración del balance de poder del Indo-Pacífico: China está alterando la paz. Y hemos sabido dejar de lado nuestras diferencias para tratar de contrarrestar el auge de Pekín en la región. Al manifestarse así estos cuatro actores, el Quad se ha convertido en el catalizador del surgimiento de otras agrupaciones, como AUKUS, que tratan de impulsar mecanismos de gobernanza regional. Para nosotros, el Quad representa la confirmación de un Indo-Pacífico multipolar que no está dispuesto a dejarse moldear por el modelo de unipolaridad que China ofrece.

¿El Quad busca competir directamente con China o pretende entablar relaciones y cooperar con ella?

Si consideramos los países que componen el Quad y sus respectivos acuerdos comerciales bilaterales con China, podemos ver que cada uno de ellos tiene a China entre sus tres o cuatro principales socios comerciales. Así pues, estos cuatro países son actores geopolíticos que son capaces de tomar decisiones racionales: no quieren ‘cancelar’ a China, pero tampoco van a dejarse intimidar por ella. Estas son las bases de compromiso que se han puesto sobre la mesa.

Source : July 13, 2023, EL MUNDO

https://www.elmundo.es/internacional/2023/07/13/6423317efdddff46058b45be.html

Digital Debates — CyFy Journal 2020

- GP-ORF SERIES

- OCT 11 2020

Digital Debates — CyFy Journal 2020

2020 is our Black Mirror moment. Each day reflecting back at us the deepest and darkest fissures of our digital societies and of our increasingly binary selves. Conversely and perversely, perhaps, our screens were also our only windows to the world, enabling us to stay connected and engaged, offering fulfillment even as the pandemic kept us apart, isolated and distant. We are, consequently, having to relentlessly engage with cleavages in society, amplified by technology, that we had buried and forgotten in the euphoria of globalisation.

Alongside our vulnerabilities, the ‘attention economy’, where human engagement with devices translates to value and valuations, grew at an unprecedented scale and intensity. From mobility to consumption and transactions, our existence became ever more enveloped in the embrace of big tech and smart tech. The pandemic had tilted the scales of an open debate, and, indeed, human activity and choices (data) were oil in this new industrial cycle. What the Gulf War was to television, COVID-19 has been to online platforms: millions were glued to personal screens, watching human death and misery unfold through the imagery of bar charts and log curves. Millions more were struggling to find — in the digital realm — means to sustain life and livelihood; and nearly all who engage with us at this conference today, were discovering their personas, politics, preferences and, indeed, identities in the world of chrome.

You are connected; therefore, you are.

As identities become indelibly linked to the online world and the apps that kept us connected, these became venues of renewed interest and importance for the state, corporates and communities to mobilise, market and manufacture consent. A heady cocktail of fear and uncertainty saw the emergence of digitally-induced conformity. From masking up to letting go of privacy and choice, we saw a global willingness to conform, submit and allow “draconian but necessary” surveillance measures — think of the submission to temperature readouts and the sharing of our travel history. In this scared and scarred new world, reality flipped over and, suddenly, it was the mobile device that carried a human. In the end, we were little more than our IP code or our mobile number. And the pandemic was certainly was not the only guilty party.

This year’s Digital Debates echoes the darker undertones of 2020 and the decade ahead of us. Through three big stories that have taken centre stage, the nine essays capture the zeitgeist of our times.

First, the pandemic has demonstrated that the workplace is inconsequential to the creation of value. Are we racing towards the threshold where humans themselves become inconsequential to work? Utkarsh Amitabh disagrees. There is infinite possibility, he says, afforded to ordinary individuals through online spaces. His essay celebrates the arrival of the passion economy, hailing the demise of the workplace as an enabler for people to monetise their skills and create economic opportunities for themselves. Manavi Jain, however, says it may be too early to ring the death knell on our coffee machine chats: our need for collaboration, and for a clear demarcation between work(spaces) and life, will compel us to return to brick and mortar offices. We may, in fact, finally see employee well- being and mental health being given the attention it deserves.

Yet, in the short-term, the outlook appears bleak. 400 million full-time jobs disappeared in the second quarter of the year and many others found themselves unwillingly trapped in circumstances that are typical to the gig economy: “flexible” work hours that served as a veneer for exploitation of labour, and the loss of a social safety net. Analogous to this phenomenon was the deification – though not appreciation in any concrete way – of essential workers in so-called low-skilled sectors. Is it time, as Sangeet Jain enquires in her lucid essay, to shed the denigration of manual labour and reassess what “valuable” work means? Paradoxically, will prolific digitalisation catalyse reassessment of how to price human labour?

Is it also time to formally price unpaid labour? While gender equality in the office space has been an agenda on HR manuals for some time now, the pandemic has taken that discussion straight into people’s homes. In a survey conducted across the cities of New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune and Kolkata [1], 50% of the women reported facing motivational challenges in the work-from-home setup as they disproportionately bore the “double burden” of taking care of household duties while holding down a full-time job. It appears that while men are willing to cede women some space in a formal office set up, they seem unwilling to lend their partners a helping hand at home. Another study showed that women accounted for 55% of the increase in job losses in the US in April this year. [2] This threatens to push back gender equality — in the now fused home and workspace — by decades.

Second, for millennia, a regime change by an external power was achieved through violent conflict, war, and annexation. Now technology allows regimes to be destabilised with a degree of simplicity. This was first brought sharply into focus by the 2016 US Elections. Disinformation, misinformation, falsehoods and lies were the legacy of that election. Millions believe that external actors shaped the US mandate. Whether it actually happened was immaterial. Perceptions were sufficient to bring about a loss of trust in institutions and the delegitimisation of the Trump presidency. As a consequence, the US of A is still a divided polity as we head into the next election cycle. This delegitimisation of regimes is agnostic to political systems — democratic, authoritarian, or otherwise. As we entered the new millennium two decades ago, technology held the promise of giving power back to the people by democratising media and communications. The opposite has happened. The imminent US presidential election has underscored the importance of regulating technology (and with it misinformation and disinformation) to secure democracy. Genie Gan canvasses the cybersecurity landscape during the pandemic, with a focus on the Asia-Pacific, and highlights how trust and transparency have become the currency that sustains partnerships between governments and businesses, and between state and citizen.

The (lack of ) trust in tech goes beyond just politics and governance. Even as we navigate the digital realm with renewed vigour during this pandemic, the safety of cyberspace has deteriorated at an accelerated pace, resulting in a scenario where age- old divides and cleavages are only getting more pronounced. The unregulated web is rife with hate speech, phishing attempts, and cyberattacks with attacks against hospitals and healthcare institutions rising by leaps and bounds during this pandemic. Those groups that faced marginalisation in the real world are facing increased aggression in the virtual, with women and minorities on social media bearing the brunt of online abuse across the world. How do we create safe spaces in a virtual world that is lightly ordered and under- regulated?

Third, technology no longer “intersects” with politics: technology is politics. The intimate enmeshing of technology and national identity has become the driving force of geopolitics, and the pursuit of technological gains is not restricted to the realm of fabs and factories, but envelops societies and global regimes and systems as well. James Lewis delves in depth into the exercise of state control in cyberspace, the so-called “Balkanisation” of the internet, while noting with acerbity that the sovereigns are simply reclaiming their role from the quasi-sovereigns, the unwieldy tech giants, whose economic worth has skyrocketed during this pandemic even as economies contracted and half a billion people faced being pushed into poverty. Elina Noor problematises this framework by pointing to asymmetries between the so-called Global North and Global South, where although the latter represents the fastest growing market for digital products and services, they are not proportionately represented in the norms and international frameworks being built around these technologies. Coining the term technology centrism, Cuihong Cai explores the different strategies — offensive or outward-looking techno-nationalism vs. defensive or inward-looking techno-nationalism — adopted by nations in pursuit of their technological goals, whether to address or maintain global asymmetries. While Cai calls for an interdependent digital community, with the well-being of people at its core, Lewis underlines cooperation between like-minded nations, noting simply, “Seeking consensus with the authoritarians is a waste of time.” Noor, meanwhile, explores the idea of true independence, where all nations are afforded the choice of placing their own self- determination front-and-centre.

In a plagued world — in both the literal and figurative sense of the word — where gated globalisation is the consensus and digital fences are visible across jurisdictions, it is crucial that we hold on to the kernel of hope espoused by the defenders of interconnectedness. Three-quarters of humanity resides in 137 developing countries, and, according to the UNCTAD Digital Economy Report 2019 [3], these countries account for 90% of global digital growth. Billions residing in these nations will be lifted out of poverty through digital tools during this Fourth Industrial Revolution. The grand finale of Digital Debates, therefore, is Nisha Holla’s piece, a clarion call for the democratisation of digital technology, emphasising inclusion, rights, legal recourse, and affirmative sovereignty. Content created must now reflect the aspirations of these billions, especially in a diverse country like India. For instance, the rise of local language content in India is perhaps inevitable with enough users coming online who are conversant only in local dialects.

The hopes and aspirations of these next billions should serve as the motivator for all to strive towards an internet for all. Just as the Cold War “hotline” was a symbol of connectedness even in the face of protracted conflict, the digital lines must remain open even if there is disagreement. CyFy exists not just to debate discord, but to find common pathways for our common humanity. Ideas and perspectives streaming this year from CyFy, New Delhi, reflect a section of the aspirations of India’s 1.3 billion people that are mirrored in Abuja, in Jakarta, in Bogota, in Dhaka and beyond.

We aspire, as we are connected.

Endnotes

[1] Brinda Sarkar, “Five in ten women facing motivational challenges in work-from-home scenario: Survey”, The Economic Times, July 20, 2020.

[2] Danielle Kurtzleben, “Women Bear The Brunt Of Coronavirus Job Losses”, NPR, May 9, 2020.

[3] UNCTAD, Digital Economy Report, September 2019, Geneva, United Nations Organisation, 2020.

ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

- COMMENTARIES

- SEP 26 2020

Geopolitics and investment in emerging markets after COVID19

Getty

As investors ponder the impact of the world’s greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression, emerging markets (EMs) face a swift reversal of fortune. Some of the fastest-growing economies in the world have been brought to a virtual standstill, reeling with the effects of an exogenous shock to demand, a public health emergency, and nascent infrastructure with which to combat the pandemic.

While multilateral development banks and international financial institutions have moved swiftly to address critical funding shortfalls, the COVID-19 pandemic has dealt severe challenges to the EM growth model — and to the livelihoods of people within these countries. As governments in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) have less fiscal space at their disposal — but harbour an ongoing need for spending on relief and stimulus measures — credit downgrades from the ratings agencies may be inevitable.

Yet, even in the wake of downgrades, this juncture of COVID-induced distress might open up a propitious opportunity for international investors and companies to invest in infrastructure in EMDEs. As such, these investors would address existing and future gaps in critical infrastructure, and ideally provide options for a green future. It will also be critical for governments within EMDE countries to align priorities with pools of institutional capital.

In light of the exceptional circumstances of COVID-19, as investors consider their portfolios, investment committees (ICs) will need to approach their geopolitical asset allocation in a creative way. As the clouds and confusion begin to clear with regard to living in a drastically altered landscape, a significant opportunity is likely to emerge for infrastructure investors to deploy capital to EMDEs with a long horizon.

With $13.7 trillion worth of negative yielding assets held in portfolios, the hunt for yield and long-term value are likely to reemerge as the concerns for safe havens begin to wane. As such, we explore potential guiding mechanisms for investors to help navigate the shifting macroeconomic and geopolitical environment in EMs, as well as potential policy recommendations for officials tasked with rebuilding their countries after the virus.

Macroeconomic snapshot: the perfect storm

Emerging markets and developing economies have faced a perfect storm in the wake of COVID-19. As the virus hit China in January 2020, emerging markets faced unprecedented capital outflows from foreign investors – dwarfing outflows during previous crises, including the 2008 Financial Crisis (GFC), the taper tantrum of 2013 (when investor panic triggered a spike in US Treasury yields on news that the Federal Reserve was slowly putting the breaks on its quantitative easing programme), and the renminbi depreciation of 2015. In the face of outflows – and depreciation of local currencies – sovereign borrowing costs have risen, thus placing a strain on the ability of many EMDE governments to continue to fight the public health emergency, as well as to shore up their economies amidst the reverberating shock to demand.

As a result of the sudden economic stops around the globe and the ongoing lockdowns, trade activity has plummeted. Commodity prices – typically a bellwether for economic growth for many EMDEs – have remained painfully low, with the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil plunging to an unprecedented nadir in negative territory. Demand for tourism – another key driver of economic growth and job creation in many emerging economies, such as Mexico, the Philippines and Thailand – remains severely curtailed. Indeed, international tourist arrivals are projected to plunge by some 60 to 80% in 2020. Remittances – another key source of national income and contribution to household purchasing power for many EMDEs – are down, and this precipitous fall is currently most pronounced in Latin America.

And, while many companies rush to secure funding from governments and capital markets, non-financial corporations in EMs continue to suffer from a debt overhang. Some $31.2 trillion sits on non-bank corporate balance sheets. At the end of 2019, an estimated $3.8 trillion of this debt was denominated in US dollars, which might place undue pressure on borrowers to service their debt in light of local currency depreciation. (If one accounts for offshore borrowing and the use of FX derivatives, the total amount of US dollar denominated debt on EM corporate balance sheets could be much higher). Looking at total debt spread across corporates, banks and sovereigns, some $7 trillion of bonds and loans are due to come to maturity in EMs through the end of 2021.

The upside: amplified macroprudential measures

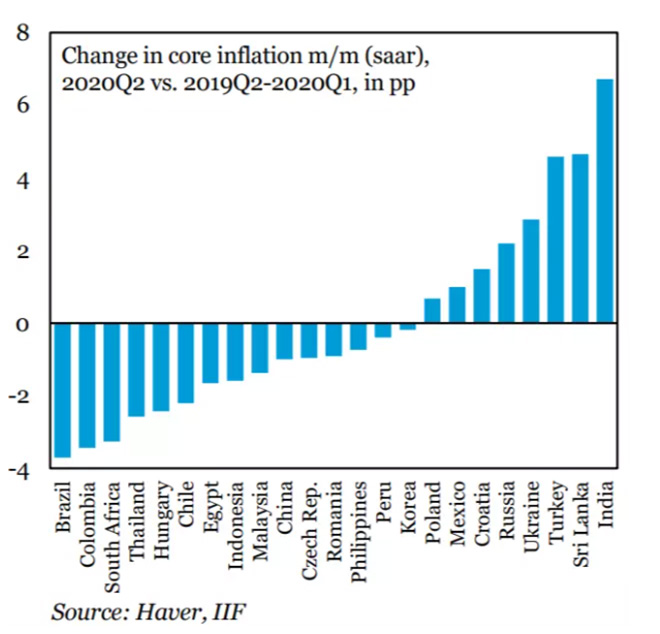

Despite this conflagration of economic challenges, governments and central banks within some EMDEs continue to exhibit a strong implementation of macroprudential policies – namely, by working to keep a lid on inflation, reducing the fiscal deficit and maintaining floating exchange rates. Core inflation (omitting volatile food and energy prices) remains muted within many EMDEs, underscoring the ability of central banks and economic officials to maintain successful inflation targeting regimes, both prior to and throughout the corona crisis. Notable examples on this front include Brazil, Colombia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Additionally, at the end of 2019, as a result of concerted efforts to reduce their fiscal deficits, Colombia posted the first fiscal primary surplus in almost a decade and Brazil posted its smallest annual fiscal deficit since 2014. As a result of lockdowns and recessions, imports have also been constrained: consequently, several countries boast current account surpluses. Notably, Brazil’s trade gap has narrowed by the greatest amount since 2007. And, although EM currencies were battered throughout the start of COVID-19, depreciation against the US dollar has largely stabilized, with some currencies significantly undervalued at the time of writing.

On the whole, central banks in EMs have been able to step in and help provide liquidity support to households and corporations hard hit by the crisis. In many cases, central banks have used the architecture and tools established during the GFC to be able to help to enable price stability and sufficient liquidity and functioning of financial markets. One EM central bank has even embarked upon the policy experiment of monetary financing; that is, of monetizing state debt by buying bonds directly from the government, rather than from the secondary market.

While foreign investors digest these moves, it is important to point out that at the time of writing, governments and central banks – acting in concert with the financial sector and central banks in advanced economies – have thus far been able to avert a financial crisis, despite the onset of a global health emergency and the worst peacetime economic slowdown since the Great Depression. While many EMDEs take up the fight against COVID-19 and its aftermath – mirroring actions and commitments from officials in advanced economies to “do whatever it takes” – EMDEs do indeed have less fiscal room for manoeuvre than developed markets.

To date, the COVID-19 fiscal response in EMs has amounted to only one-fifth of that of advanced economies. In contrast, countries such as the US can reap more fiscal space by being the world’s reserve currency. Additionally, some eurozone bonds (such as the German 10-year bund) are also considered to be a safe haven for some institutional investors.

Amidst mounting sovereign debt and constrained fiscal space, credit downgrades in EMs have begun to unfurl, posing a challenge to the ways in which investment committees traditionally approach geographical asset allocation. In the wake of a downgrade, it is important for investors to take a step back and ask the following questions:

- Which countries demonstrated a robust commitment to implementing macroprudential measures prior to the outbreak of COVID-19?

- Which countries have a strong domestic market, rendering them somewhat resilient in the face of an exogenous shock?

- Which countries have boasted strong labour force productivity, with a commitment to boost competition in sectors of long-term demand in the post-COVID recovery landscape?

Even if a country receives a downgrade as a result of its enhanced fiscal efforts deployed to help combat COVID-19 and to address the exogenous shock of the pandemic, it is important to recognize that for some countries, these efforts are an expansion of spending during exceptional circumstances, rather than a departure from an overall commitment to macroprudential measures.

Reading the tea leaves: geopolitics and deploying long-term capital to infrastructure

While we might recognize that there are some countries that fit the bill in terms of their economic planning and policy, for investors looking to EMDEs, geopolitics can often cloud the landscape for investing. For the private sector, and specifically investors and executives, geopolitics relates to infrastructure in three key ways:

1) Geopolitical asset allocation, at the portfolio level

On a country-by-country basis, which countries manifest the strongest risk-reward ratios? Here, it is important for investors to distinguish between absolute and perceived risk. For example, an institutional investor with little risk appetite might consider investing in airports in Paris to be a geopolitically low-risk investment, versus deploying capital to airports in Vietnam, which might be perceived as higher risk. However, in light of the rise of populism in advanced economies, and risks of potential nationalization, some countries or regions perceived to be less geopolitically risky might indeed harbour more absolute risk.

2) Managing geopolitical risk, at the asset management level

While operating assets on the ground, infrastructure investors are often confronted with effectively managing geopolitical risk at the asset level. Several questions that may need to be addressed include: how might any (small or large) breach of project safety engender a shift in perception by the host country, potentially rendering the investor a target of local political ire? How might changes in the regulatory environment affect investments, and how might investors anticipate potential changes in the regulatory environment? How might investors best navigate potentially conflicting positions between federal, provincial and municipal authorities? Recognizing that taxes can become a tool amidst a rise in geopolitical tensions, how might investors be able to anticipate potential changes in taxation that might hinder their position, both in terms of profits and also in ease of operation?

3) The intersection between geopolitics and economics

Infrastructure investing has the power to spur a positive feedback loop within an economy. By creating both direct and indirect economic growth and employment, and improving livelihoods and quality of life, greenfield infrastructure investments can provide a foundation for generating economic growth via agriculture, manufacturing and service activity. Brownfield infrastructure investments – including upgrades to existing assets – have the potential to greatly enhance the quality of life in a given area, as well as to boost efficiency (for example, upgrading a toll road can ease traffic and congestion). By acting as a foundation and a multiplier effect of economic growth and quality of life, infrastructure investments can, over time, potentially reduce geopolitical risk by contributing to livelihoods and generating economic opportunities.

In trying to discern which EMDE countries may prove attractive for investment, it is advisable for investors to identify which governments exhibit a strong capacity for follow-through on policy reform. In order to attract voters – or possibly, foreign investors – political leaders might promise many pro-growth or pro-business policies. To promise is, of course, not enough. The question for investors is: which countries have demonstrated the potential to ratify and implement such change?

For example, the Brazilian Congress ratified the country’s historic pension reform in October 2019. Although this had been a policy priority of the current and previous presidential administrations, the country’s legislative body followed through on the reform. In the case of India, while many executives and investors had complained about the opacity of the country’s complex tax system, the implementation of the goods and services tax (GST) greatly simplified taxation. Sometimes, policies such as the GST might induce short-term pain for long-term gain. For investors, It is advisable to identify signs from governments which might harbour this long-term vision – and the capacity to see it through to implementation.

For investors, it is advisable to identify signs from governments which might harbour this long-term vision — and the capacity to see it through to implementation. Partly, this depends upon the strength of existing institutions, as well as the ability to reform institutions as the need arises. Notably, in the case of Brazil, while some investors have been deterred from the ongoing Lava Jato investigations, this demonstrates the strength of the institution of justice.

Crucially, it is not necessarily only democracies which exhibit the capacity for follow-through on pro-business and growth-oriented policy reforms, as well as the ability to constructively reform institutions. Vietnam is a key example here, where foreign and institutional investors continue to respond positively to the government’s ongoing market reforms by deploying billions of dollars to the country. Again, taken together with a consideration of which governments might harbour a commitment to macroprudential measures, a tried-and-tested capability for follow-through on policy reform may also be a signpost for investment committees to identify in light of a potential downgrade.

At the sector level: building back green

In the World Economic Forum’s Great Reset initiative, as many governments chart out policies to constructively rebuild their countries in the aftermath of COVID-19, a clear emphasis is placed on addressing critical gaps in soft infrastructure, which may help enable countries to withstand a health crisis or a sudden stop in economic activity. This includes hospitals and public health institutions, broadband connectivity, educational platforms to continue teaching in a virtual classroom, and supporting sustainable food security, access to clean water and personal protective equipment (PPE).

Of course, these investments are not limited to EMDEs. Advanced economies such as the US and France have worked to address some of these gaps in critical infrastructure in the wake of the pandemic. Accordingly, these types of soft infrastructure categories – rather than the hard infrastructure of ports, roads, airports and bridges – are likely to be immediate policy priorities for some EMDEs in magnetizing foreign investment. Utilities and power are also likely to rank high on the list, insofar as power underpins this softer infrastructure.

In considering economic vitality after COVID-19 – and to do so in a way that shapes a more sustainable and resilient future – governments across the globe have touted green and digital as key policy priorities. However, in order to attract foreign investment, EMDEs will need both strong institutions, as well as the capacity for institutional reform, which would possibly then foster a sense of confidence in fund managers that these might be deployed effectively.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) indices have outperformed traditional benchmarks during the current pandemic and are likely to attract more funds going forward. Nevertheless, it is crucial for ESG investors to identify jurisdictions with clear green taxonomies and government policies designed to enhance innovation and market creation.

Government action, alone, can’t do the job: the private sector will have to be the locus of climate action. This should require a fresh focus on the ease of doing business, policy certainty and a regulatory landscape, which prioritizes green sectors. Undoubtedly, for many companies facing high fixed costs and negative sales – as well as heightened uncertainty about the future – the coronavirus pandemic has constrained the ability for some corporations to deliver on past commitments to consume green energy.

A critical question to address in the post-pandemic era will be the creation of new growth centres and adaptations of growth models. In EMDEs, cities have been the locus of economic activity and have successfully brought millions out of poverty. However, as the current pandemic – or recent waves of natural disasters – show, one shock can risk undoing the work of years and potentially push millions back into poverty. Highly dense urban centres can also put pressure on both the environment and natural resources. As the risks of climate change mount, growth models in emerging markets should need to prioritize resilience and quality of life, alongside efficiency and profits. This can include the rapid development of smart cities, something Singapore has done remarkably well.

Additionally, while parts of global value chains might be onshored in the wake of COVID-19, a potentially significant opportunity arises for international investors to deploy capital for localizing supply chains. A well-developed domestic supply chain may require improved connectivity, both physical and digital. Digital platforms and knowledge sharing will likely be integrated nodes on the value chain. Smaller self-contained habitats will be required for workers, and sustainable solutions are likely to be needed for housing, mobility and utilities, as well as natural resource management.

Investments in clean power should be requisite to underpin both old and new economic growth: that is, for industrial activity and digital connectivity. Finally, these countries will need to develop the human capital required to carry out jobs that are likely to rely upon increasingly complex technologies. Catalyzing infrastructure investment in the wake of COVID might provide much-needed jobs, and may also sow the seeds for future skills to meet changing patterns of demand in the new economy.

Conclusion: getting it right

In the pre-COVID age, one advanced economy within the Asia-Pacific region has managed to deftly invest in infrastructure in developing countries for the long haul: Japan. Indeed, Japan has had a long history of exchanging overseas development assistance for resources to fuel its manufacturing growth. In later years, it has become an exporter of what Prime Minister Shinzo Abe calls “quality infrastructure investment”.

Recipient countries such as India have affirmed the high quality of such investments – including bullet trains and subway stations – and the Japanese government has also prioritized the facilitation of knowledge exchanges to help nurture and develop human capital. Critically, Japanese infrastructure investment is not necessarily hinged upon whether a country is classified as a democracy, suggesting that both lucrative profits and economic and financial stability may not just emanate from states which profess to be democratic.

It should be noted that Japan has been criticized for its use of coal at home and for its development of coal plants abroad. Indeed, even in light of commitments made by several Asian governments (most notably, South Korea) to “build back green”, Japan has allocated only a nominal amount of the country’s $2.1 trillion COVID relief package toward the green energy transition. However, as relief segues into stimulus and the global economy inches toward recovery in a post-pandemic world, Japan has the potential to help provide an environmental component with its quality infrastructure investments. Indeed, Environmental Minister Shinjiro Koizumi recently announced increasing regulation for building coal power plants overseas — a move that is in keeping with the Japanese business community’s action to help reduce carbon emissions.

Similarly, Australia has declared its intention to become a “renewable energy export superpower” with a commitment to export solar energy to Singapore via cables and the use of the world’s largest battery. A resource-rich country known for exporting coal and natural gas around the world, Australia has the potential to build upon its past relationships and know-how to help bolster the energy transition within emerging markets and advanced economies alike.

In a world of competing visions within foreign policy, both Japan and Australia demonstrate that it is possible to invest abroad without ideology and preconditions – which is a straightforward approach, and likely necessary to help address infrastructure gaps around the globe.

Finally, while infrastructure investors can look to generate profit in EMDEs over the long term, it is advisable for the governments within these countries to explain to their voting publics the importance of attracting foreign capital. This requires clear data, and also versatility in how this data and story is communicated to different interest groups – be it provincial or municipal governments, citizens or local businesses. The story needs to continue throughout the lifespan of such investments – and indeed, potentially after completion.

Development banks within host countries can help provide such continuity amidst changes in administration at the federal level. It is also worth exploring the ways in which some development banks can become independent entities, rather than organized via political appointments. This might provide a much-needed ballast for the dry powder that waits in the wings – and for institutional capital with nascent exposure to infrastructure in emerging markets.

This commentary originally appeared in World Economic Forum.

Gated globalisation and fragmented supply chains

The hyper-globalisation processes that built China’s industrial might also caused enormous political churn.

For decades, the West, led by US strategic thinking, bet that full-on engagement with Beijing would alter the opaque nature of Chinese politics, making it more liberal and open. The onset of the Covid19 pandemic should ensure a quick burial to this belief. The free and open liberal world order has run into the great political wall of China with deleterious consequences. Not only did the intense engagement with China fail to alter its politics, but many liberal democracies have also adopted Chinese-style industrial planning policies. The irony of today’s geopolitical moment is that Western taxpayers underwrote China’s bid for global influence. Successive US administrations, egged on by Big Business and Big Finance, played a crucial role in bringing China into the global community, culminating in Bill Clinton’s decision to welcome China into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) system.

Building Its Appetite

The subsequent outsourcing of manufacturing and industrial capabilities from the West to China allowed Beijing to ‘bide its time’ as it strategically built its influence through control over global supply chains. Because of the enormous financial returns accruing from labour arbitrage, governments turned a blind eye, as China used this economic dependence to flex its political muscle, first in Asia and now, through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), into the very heart of the European Union (EU).

The hyper-globalisation processes that were steadily building up China’s industrial might were simultaneously causing enormous social and political churn among the Western working and middle classes. Shorn of the decent wages afforded by manufacturing jobs — and increasingly alienated from the financial and technology elite — those left behind turned against globalisation.

The hyper-globalisation processes that were steadily building up China’s industrial might were simultaneously causing enormous social and political churn among the Western working and middle classes

The current global pause induced by Covid19 offers us a moment to reflect on what was, and to examine the contours of, what may well be Pax Sinica. Two large projects define China’s recent emergence. The first, reminiscent of Pax Britannia and Pax Americana, is the much-discussed BRI. China’s outward expansion through the construction of new supply chains and trade routes has been designed to serve its economic interests by capturing the flow of raw materials from Asia and Africa and, thereafter, supplying finished products to the world. And just as the British packaged their imperial design as a show of benevolence — think of the argument that the railways in India were built to benefit Indians — so, too, is China selling its political proposition as a new pathway for global growth, solidarity and development.

The second aspect of its expansion relates to technology, and its concerted effort to control and leverage the global data economy for itself. By globalising its technological prowess — from building next-generation communications infrastructure and digital platforms to offering surveillance tools to authoritarian governments — Beijing is well-positioned to script future administrations and regimes around development, finance, and even war and conflict. And it does this even as it isolates its own people from external flows of information and technology. Some argue that Pax Americana was no different. Like Beijing, the US leveraged its pole position in the global economy, its military and industrial strengths, and its technological supremacy to build a world order that responded to its interests. There is, however, no equivalence between the two. US society was largely open —individuals, communities and nations from around the world could engage, convince or petition its institutions; write in its media; and, often, participate in its politics. Its hegemony was constrained by a democratic society and conditioned by its electoral cycles.

US society was largely open —individuals, communities and nations from around the world could engage, convince or petition its institutions; write in its media; and, often, participate in its politics. Its hegemony was constrained by a democratic society and conditioned by its electoral cycles

Recipe’s Old, Mistrust’s New

It was these characteristics that encouraged nations to place some degree of faith in multilateral institutions, which were largely underwritten by the US. It also encouraged countries to participate in the free flow of goods, finance and labour; to move towards open borders, markets and societies; and, indeed, to embrace USled globalisation at the turn of the last century.

Few will be able to navigate the dark labyrinth of Chinese politics, much less claim to influence its communist party. It is worth recalling that at the peak of its might, the US withdrew from Vietnam because intense media scrutiny dramatically undermined public support for the war at home. Will images of damage to the livelihood and ecology along the Mekong convince the Communist Party of China (CPC) to abandon its damming projects upstream? Will the thousands of deaths caused by Covid-19 within China make it more transparent?

Therefore, the next globalisation era, increasingly underwritten by Beijing, may well be less free and less open than before. To balance China’s global ambitions, nations may opt to trade with geographies and nations where political trust exists, thereby fragmenting supply chains. Governments will ‘gate-keep’ flows of goods, services, finance and labour when national strategic interests are at stake. Indeed, we should be ready for a new phase of ‘gated globalisation’. Even as the recovery and progress of the post-Covid-19 world will be worse for it.

This commentary originally appeared in The Economic Times.

Order at the gates: globalisation, techphobia and the world order

The publication of this commentary marks the beginning of online collaboration between Valdai Club, Russia as part of its Think Tank project and the Observer Research Foundation, India. This is the first in a series of planned exchanges between the two organizations on bilateral and global matters. Stay tuned for more commentaries, videos and webinars in the days ahead.

Nearly three decades ago, Francis Fukuyama argued that the imminent collapse of the Soviet Union and the universalisation of liberalism would mark an end to the historical struggle over ideology and political models. His thesis was, by his own recent admission, overly optimistic. The resurgence of strong identities and nationalist leaders has given rise to the politics of resentment and tribalism. Coupled with new shifts in the global balance of power and disruptive technological and industrial processes, it’s clear that a new world is upon us. The onset of the novel coronavirus at the turn of this decade has accelerated many of the processes that were a compelling change and has compressed timelines for governments, businesses, and communities to make crucial decisions about the future.

Perhaps the most significant of these shifts is the unmistakeable demise of Pax-Americana. The COVID19 outbreak is the first global challenge that has witnessed the complete absence of American leadership. It has also thrown into sharp relief the social and governance vulnerabilities of the West more broadly. Even the EU has struggled to equitably distribute resources between its member states amidst this pandemic with many now openly expressing their reliance on China — a result of expediency and naivety. The divisions — between North and South Europe over economics, and Western and Eastern Europe over values — seems likely to widen. The weakened transatlantic core of the international liberal order is likely to slip further in relevance in the post-COVID world.

Even so, it is not immediately obvious that any new leadership will take charge in the future. China, which by most estimates is a leading contender, has drawn the ire of the international community for several interrelated reasons, beginning with its missteps in containing the virus. Despite efforts to launder its own image through the WHO and the provision of public health goods to various regions, its efforts to sow discord among EU member states and its muscularity in dealing with Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the South China Sea littorals is not winning it any friends. The documented racism towards its African diaspora has added to the list of nations and communities that are re-evaluating their dependence and relationship with the middle kingdom.

Most nations are struggling to adjust to the fast changing and evolving balance of power equations between China and the western hemisphere. East Asian democracies, which have arguably responded most effectively to the outbreak, have watched these goings on with anxiety. It is clear that they will continue to play one against the other and carve for themselves room to manoeuvre. Russia, which was amongst the first to limit travel to and from China, is now being threatened by an outbreak in its own cities. It will nonetheless continue to bolster Beijing’s agenda as long as it undermines what Moscow has always believed to be, a fundamentally undemocratic world order managed under US hegemony. It would be interesting to see how Russia — under its presidency — steers the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) to respond to the series of disruptions that the world is grappling with.

Russia, which was amongst the first to limit travel to and from China, is now being threatened by an outbreak in its own cities. It will nonetheless continue to bolster Beijing’s agenda as long as it undermines what Moscow has always believed to be, a fundamentally undemocratic world order managed under US hegemony

These interrelated disruptions in various geographies also dovetail into another broader trend: The return of the strong state and the normalisation of nationalist leadership. The coronavirus outbreak will act as a catalyst for this process. Some governments will use emergency and national security powers to consolidate power, as Hungary’s Orban already has. Others may use this as an excuse to blame and undermine international institutions — the preferred bogeyman of the Trump Administration. And many will enjoy the popular support of their citizens as they do so.

The most obvious impact of these developments will be the end of globalization as we know it. Most states will aggressively move to reduce interdependence, especially with those regions where political trust is limited. Japan’s efforts to incentivise its industry to diversify supply chains away from China through a stimulus package is indicative of this. But the ripple effect of these decisions will be felt across geographies — from the Gulf states, who are struggling to maintain supply of oil and manage flows of labour; to the ASEAN, which will see enormous disruptions to its trade flows that are deeply intertwined with both China and the US.

Indeed, a shift from a global village of relatively deeply integrated communities to a form of “gated globalisation” based on political and economic familiarity appears inevitable. The digitisation of the global economy will only accelerate this process and, perhaps, technology tools may well aid in this. As governments take advantage of digital and surveillance tools to combat the COVID19 outbreak — in societies both liberal and illiberal — a new ‘techphobia” will begin to affect foreign technology platforms and businesses. With nearly all social, economic, and strategic interactions moving to the virtual and digital realm, states will race to “encode” their political values and technology standards into the algorithms and infrastructure that will govern our societies. This will certainly be a competitive process which will give birth to a persistent “code war”.

With nearly all social, economic, and strategic interactions moving to the virtual and digital realm, states will race to “encode” their political values and technology standards into the algorithms and infrastructure that will govern our societies. This will certainly be a competitive process which will give birth to a persistent “code war”

Most worryingly, the international community’s ability and willingness to tackle collective challenges through global efforts will be irredeemably harmed. From the G20 to the UNSC, few international institutions have proved capable of responding to the pandemic with any level of speed or efficacy. Other institutions, like the WHO, have been subject to political capture and manipulation, adding to the waning global trust in these bodies. There is a dangerous fragility now to global co-operation — with uncertain implications for future challenges of this scale. What will this mean, for instance, when climate change begins to redraw coastal lines, cause food shortages, exacerbate inequality and strain national resources like never before? If the global response to the COVID19 outbreak is any indication, it will be every nation for itself, with many suffering horrible consequences as a result.

The coronavirus may have heralded the sudden onset of what Ian Bremmer calls a “G-Zero” world — one that is at once multipolar, leaderless, and likely besieged by renewed geopolitical conflict. It will be a world where the West has lost its “moral” authority and one that Beijing seeks to reshape through its muscular and expansive Belt and Road Initiative; one where the Kremlin will see an opportunity to expand its geopolitical ambitions in East Europe, West Asia and the Arctic; and one where nations without geopolitical or geoeconomics prowess will have to “pick sides”, either by constraint or compulsion.

The coronavirus has certainly shone a torch on a world disorder, one where most communities are likely to be plagued by poverty, conflict, unemployment and inequality, while great powers either look away or cast their material resources towards their own populations and self-interest

The coronavirus has certainly shone a torch on a world disorder, one where most communities are likely to be plagued by poverty, conflict, unemployment and inequality, while great powers either look away or cast their material resources towards their own populations and self-interest. Plurilateral efforts such as at the G20, G7, the BRICS, the OSCE and the SCO, among others, may become the only viable venues where key global actors coordinate and convene with purpose, and will be the arenas where actors who are unable to engage in meaningful conversations can speak through proxies. Will these become the norm builders for “gated globalization” or can we find it within us to repurpose, resuscitate and radically reform the UN as it turns 75 to help shape a common future?

Great Wall for China? Shaping China’s (mis)behaviour

Mitigating the adverse impact of Beijing’s crude ambition while simultaneously absorbing Chinese capital is a tough balancing act. Before making policy choices, India must rapidly improve its ability to monitor the full extent of economic exposure to China.

To essentially prevent Chinese capital from taking over distressed businesses, India amended foreign direct investment (FDI) rules on Saturday to mandate government approval for all investments from ‘border’ countries. This is undoubtedly a critical crossroad in the India-China relationship. But it cannot be understood in isolation from other consequential bilateral shifts. These changes first began meaningfully in May 2017, when India objected to China’s efforts to reshape the Asian continent using the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

For decades, India and China were imagined by many as the future co-guarantors of the ‘Asian Century’. This changed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when China saw an opportunity to cement its leadership by establishing either a multi- or bipolar world while shaping a firmly unipolar Asia. India fully internalised this reality only after Beijing repeatedly ignored Delhi’s call to ‘multilateralise’ BRI, and mounted an offensive in Doklam, on the Bhutan-China frontier and perilously close to the ‘Chicken’s Neck’ corridor that links India’s Northeast to the rest of the country.

The coronavirus pandemic has finally compelled India to respond to its geo-economic realities. Still, much work remains. The current FDI restriction is a blunt instrument that is just as likely to harm Indian economic interests even as it seeks to protect them. China is the world’s second-largest economy, and as a March Brookings India paper, ‘Following the Money: China Inc’s Growing Stake in India-China Relations,’ by Anant Krishnan estimates, it has invested at least $8 billion in the Indian economy over the past six years.

If India is to make its way to a $10 trillion economy by the early 2030s, it may find it difficult to do so without a more robust trade and investment relationship with China. However, there are two aspects to China’s economic behaviour that India must not ignore. The first is Beijing’s efforts to ‘weaponise’ interdependence. Ever since China became central to global supply chains, it has used perverse industrial tools to climb the value chain, exacerbate trade imbalances and undermine global competition.

The second is China’s effort to shape the future of digital globalisation. It is exporting its propositions through the ‘Digital Silk Route’ and monopolising strategic industrial technology through the ‘Made in China 2025’ initiative.

Mitigating the adverse impact of Beijing’s crude ambition while simultaneously absorbing Chinese capital is a tough balancing act. Before making policy choices, India must rapidly improve its ability to monitor the full extent of economic exposure to China. As Krishnan’s study demonstrates, official figures do not shed light on Chinese investments through subsidiaries or other commercial instruments. It should not appear that India is lazily blocking Chinese investment largely because China has blocked market access to Indian companies in pharmaceuticals, dairy products and IT services.

India will have to identify the sectors that implicate its national and economic security. There is no granularity to the current FDI restrictions. Not all Chinese investments are national security threats. China’s investments in the automobiles industry, for instance, is less likely to be a security risk than those in India’s technology sector, whether it is infrastructure like 5G or in software and its applications.

Finally, New Delhi will have to develop new legal and institutional tools. Even the US and EU member states have not relied on such extensive FDI restrictions, despite Beijing’s aggressive acquisitions in their sensitive sectors. Instead, both are employing a combination of sectoral legal tools, such as data protection laws or revised mergers and acquisitions rules, and institutional bodies, like the US Committee on Foreign Investment. Without the appropriate legal and regulatory sanction, India might expose itself to reciprocal measures.

This is also part of a broader trend defining globalisation: the era of free and open trade may be at an end. The future may be characterised by ‘gated’ globalisation, where economic relationships will have to be underpinned by political trust. India stands to gain from this. Its political familiarity with large trading blocs like the US, EU and Japan make it a far more secure economic partner than China.

If this moment is inevitable, India must also work with its partners to shape and influence China’s economic behaviour.

This commentary originally appeared in The Economic Times.