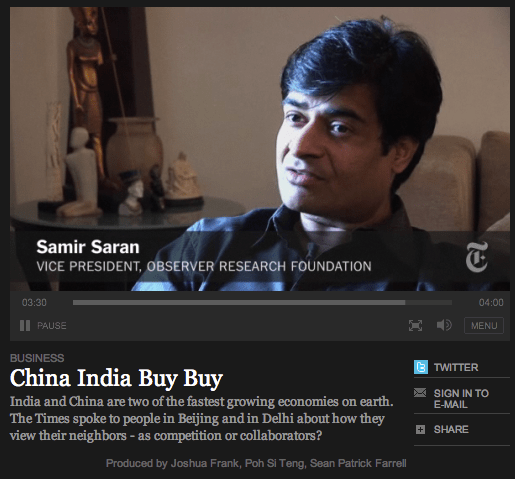

by Samir Saran & Jaibal Naduvath

For over six decades, India’s relations with Russia and its predecessor, the erstwhile Soviet Union, have remained very cordial. From the heady heights of being “near allies” during the Cold War era to a brief pause in the 1990s as both countries recalibrated their own identities during a period of dramatic political transformation in each country, the Russia-India relations have endured dramatic shifts in global politics. Over the past 20 years though, there has been a pragmatic remoulding of the content of this engagement alongside an assured continuity on crucial areas of traditional cooperation like the defence sector. The non-continuance of the Indo-Soviet Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1971, seen by many as India’s security insurance during the cold war years, the subsequent Declaration of Strategic Partnership signed by the two countries in 2000, and renewed co-operation and strategic engagement at multilateral fora such as BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the UN reflects diplomatic maturity and political realism in equal measure. However, despite the long-standing bonhomie, close trade ties and multiple cultural and political exchanges, Russia has not managed to emotionally engage the Indian psyche as much as it should have, even though the very mention of Russia evokes feelings of great warmth among most Indians. However, meaningful interest in Russia remains confined to the foreign policy elite, emancipated urban dwellers and business and trade communities with interests in the opportunities that Russia offers. In the larger public discourse Russia continues to be viewed through the prisms of defence and strategic relationship and the ‘energy narrative,’ with media and polity both guilty of selectively amplifying developments that impact these aspects. As a result, the response on the Indian street often tends to be binary and simplistic to what is transpiring in contemporary Russia. Media reportage and public discourse in India on the upcoming presidential elections in Russia is prey to this myopic syndrome. Indeed, Russia accounts for a majority of all Indian military imports and the reliability of such defence sales is vital for India. A stable Russia and more importantly a political dispensation in Kremlin that supports this defence sector engagement is crucial. There is, however, an urgent need to widen the discussions and media narrative on Russia, if there is to be meaningful and contemporary appreciation of this most significant ally in India.

As things stand, very little is known of presidential candidates other than Valdimir Putin, who has visited India several times, and is considered sensitive to this country’s interests. However, there is also a tacit realisation that sweeping political changes globally and reverberations in Russia which culminated in highly publicised street protests in Moscow (albeit modest in size and scale) against allegations of vote rigging in the parliamentary elections have led to a decline in Putin’s standing, rendering him more vulnerable than before. There is also a feeling that Putin losing his aura of invincibility, and the possible devolution and decentralization of power in Kremlin, could actually usher in greater pragmatism into the Russian political ecosystem making it a lot more dynamic and democratic, and, easier for others to empathise with. Despite being challenged by sections of Russian civil society, Putin may not have lost much of his personal brand appeal in India yet, for two reasons. First, very little is known of the opposition within Russia and even less so is available in Indian media. Secondly, dissent, discord, rebellion are all part of the political landscape in India and the leadership is indeed defined by the ability of the leader to resolve and navigate such challenging terrain. India itself has been ruled by coalition governments intermittently for over two decades with arguably, reasonable success. From their own experience, Indians could relate better to Putin if he is able to manage and share political space and carve out a consensus. Putin, slightly vulnerable and in the need for reaching out, makes him more attractive to the Indian people and its enterprises than Putin the steely and authoritarian figure.

The feeling is that under his potential future presidency, Putin may have to cede at least some ground to factions within his United Russia Party. Who the factions are and what their dispositions and agendas would be are unknown. In the coming days, prior to the March elections and certainly, if voted to power, in the period after Putin’s election, the main interest in policy circles in India, would be the sort of ‘arrangement’ Putin may need to put in place to manage dissent and preserve his influence.

Who (all) he devolves power to and how that impacts Russia’s external engagement will be important to India. As a global military power, Russia affords great counterbalance for India vis-à-vis China. If a pro-China faction emerges at the Kremlin, it will have the potential to further fuel China’s own ambitions in Asia and may drive India to develop a deeper partnership with the United States and other Asian powers to offset it. On the other hand, if the new power structure allows greater Russian outreach to the US and the European Union, it would not only balance the rise of China, but also help India and Russia develop a partnership beyond defence sales, elevating their engagement to a wider set of issues including, on managing the global commons.

From an establishment standpoint, India has always accepted organic development of national political systems and hence is unlikely to be either unduly concerned or patronising as long as its core strategic concerns are not jeopardised. Muted media interest and public response to the Moscow street demonstrations, dramatic developments in a system with little tolerance for political dissent, needs to be seen in this light. Also, after having witnessed the upheavals in the West Asia and North Africa (WANA) region, the media coverage of the Occupy Wall Street agitation and the highs and lows of the civil society movement against corruption at home, the larger Indian public is unlikely to be very taken in by the limited protests in Moscow.

The Indian public sphere is unlikely to engage comprehensively with the happenings in the run up to the Russian elections. On the other hand, the Indian establishment will keenly follow political developments in Russia as the importance of the election outcome and its impact on both the Asian strategic architecture and bilateral relations is not lost on them. The two countries have enormous potential for greater strategic convergence and a favourable political dispensation in Moscow could well catapult the India-Russia relationship into one of the defining global partnerships of this century.

Samir Saran is Vice President at the Observer Research Foundation, a leading Indian policy think tank and Jaibal Naduvath is a communications professional in the private sector in India

Assessing the current strategies adopted by the Centre and various affected State Governments to counter the spread of the left wing extremist in more than 200 districts of India, a participant pointed out that the Salva Judum strategy of the government has been one of the main causes of the growth of Naxalism. It was pointed out that no rehabilitation and compensation has been made by the government of Chattisgarh to the people who had lost everything.

Assessing the current strategies adopted by the Centre and various affected State Governments to counter the spread of the left wing extremist in more than 200 districts of India, a participant pointed out that the Salva Judum strategy of the government has been one of the main causes of the growth of Naxalism. It was pointed out that no rehabilitation and compensation has been made by the government of Chattisgarh to the people who had lost everything. The discussion questioned the “elitist development model” in tribal areas. It was noted that the current development model measured only by GDP growth and encourages corporate interests has destroyed the livelihood of the tribal people as most of their land were taken away for mining and other industrial projects. Both government and corporate had gone and uproot the tribals in their own land without showing any respect for the tribal people, their culture, their traditional knowledge, their civilisational strengths and their land.

The discussion questioned the “elitist development model” in tribal areas. It was noted that the current development model measured only by GDP growth and encourages corporate interests has destroyed the livelihood of the tribal people as most of their land were taken away for mining and other industrial projects. Both government and corporate had gone and uproot the tribals in their own land without showing any respect for the tribal people, their culture, their traditional knowledge, their civilisational strengths and their land. On the political front, it was suggested that there was a need to re-look at the current governmental structures at the district and block levels. A participant suggested that the first priority of the government has to be to restore civil administration in the affected states and districts. A participant noted that change in government structures at the block level could be an effective way to ensure better representation of local people who are better placed to understand local issues and problems. Also, such as gesture could also give a sense of justice to the people. It was also suggested some autonomous areas could be created for the tribal people through that a sense of local control over its own people and resources could be ensured.

On the political front, it was suggested that there was a need to re-look at the current governmental structures at the district and block levels. A participant suggested that the first priority of the government has to be to restore civil administration in the affected states and districts. A participant noted that change in government structures at the block level could be an effective way to ensure better representation of local people who are better placed to understand local issues and problems. Also, such as gesture could also give a sense of justice to the people. It was also suggested some autonomous areas could be created for the tribal people through that a sense of local control over its own people and resources could be ensured. A participant noted that there was a need to re-look at the Salva Judum policy. Another participant pointed out that the traditional police force cannot deal with the Maoist challenge and there was a need for special training. A participant felt that there was a need for appropriate security force to deal with the Maoist problem to minimize collateral damage. Most of the participants felt the army should not be used also against the Maoists.

A participant noted that there was a need to re-look at the Salva Judum policy. Another participant pointed out that the traditional police force cannot deal with the Maoist challenge and there was a need for special training. A participant felt that there was a need for appropriate security force to deal with the Maoist problem to minimize collateral damage. Most of the participants felt the army should not be used also against the Maoists.