Tag Archives: Observer Research Foundation

Raisina Files 2021 aims to engage with the leitmotifs of this past pandemic year, mirroring the theme of the Raisina Dialogue 2021, “#ViralWorld: Outbreaks, Outliers and Out of Control”. Within this overarching theme, we have identified five pillars and areas of discussion to critically engage with—WHOse Multilateralism? Reconstructing the UN and Beyond; Securing and Diversifying Supply Chains; Global ‘Public Bads’: Holding Actors and Nations to Account; Infodemic: Navigating a ‘No-Truth’ World in the Age of Big Brother; and, finally, the Green Stimulus: Investing in Gender, Growth and Development. Together, these five pillars of the Raisina Dialogue capture the multitude of conversations and anxieties countries are engaging and grappling with.

Raisina Files is an annual ORF publication that brings together emerging and established voices in a collection of essays on key, contemporary questions that are implicating the world and India.

In this volume

Editors: Samir Saran, Preeti Lourdes John

- Emerging Narratives and the Future of Multilateralism | Amrita Narlikar

- Diplomacy in a Divided World | Melissa Conley Tyler

- Is A Cold War 2.0 Inevitable? | Velina Tchakarova

- Trust But Verify: A Narrative Analysis Of “Trusted” Tech Supply Chains | Trisha Ray

- Can The World Collaborate Amid Vaccine Nationalism | Shamika Ravi

- A Nuclear Insecurity: How Can We Tame The Proliferators | Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan

- De Facto Shared Sovereignty And The Rise Of Non-State Statecraft: Imperatives For Nation-States | Lydia Kostopoulus

- Digital Biases: The Chimera Of Equality And Access | Nanjira Sambuli

- The Infodemic: Regulating The New Public Square | Kara Frederick

- How Finance Can Deliver Real Environmental And Climate Impact | Geraldine Ang

- Unlocking Capital For Climate Response In The Emerging World | Kanika Chawla

- Putting Women Front And Centre Of India’s Green Recovery Process | Shloka Nath, Isha Chawla, Shailja Mehta

- Investing In Material Innovation Is Investing In India’s Future | Nisha Holla

Read here – https://www.orfonline.org/research/raisina-files-2021/

Raisina Files 2021

Raisina Files 2018 unpacks disruption and its interaction with global politics. Disruptive forces have been grouped along the lines of actors, processes, and theatres: three major nation-states whose external engagements are seeing shifts; three processes that are re-organising political, economic, and social spaces; and two old and new arenas where geopolitics are having local, regional, and global repercussions.

Raisina Files, an annual ORF publication, is a collection of essays published and disseminated at the time of the Raisina Dialogue. It strives to engage and provoke readers on key contemporary questions and situations that will implicate the world and India in the coming years. Arguments and analyses presented in this collection will be useful in taking discussions forward and enunciating policy suggestions for an evolving Asian and world order.

- Debating Disruption: Change and Continuity | Ritika Passi and Harsh V. Pant, ORF

ACTORS

- Is the US a disruptor of world order? | Robert J. Lieber, Georgetown University

- Russia as a disruptor of the Post-Cold War order: To what effect? | Dmitri Trenin, Carnegie Moscow

- China as a disruptor of the international order: A Chinese View | Yun Sun, Stimson Center

PROCESSES

- Globalisation, demography, technology, and new political anxieties | Samir Saran and Akhil Deo, ORF

- Minority Report, Illiberalism, intolerance, and the threat to international society | Manu Bhagavan, Hunter College

- Fourth Industrial Revolution: Evolving Impact | Pranjal Sharma, author, Kranti Nation

THEATRES

- Revolutionary Road: Indo-Pacific in Transition | Abhijnan Rej, ORF

- Middle East: Cascading Conflict | Tally Helfont, Foreign Policy Research Institute

- Climate Change, Transitions, and Geopolitics | Karina Barquet, Stockholm Environment Institute

Read here – orfonline.org/research/debating-disruption-world-order/

Debating Disruption in the World Order

A LONG-TERM VISION FOR BRICS

Original link is here

The objective of this document is to formulate a long-term vision for BRICS. This in turn flows from substantive questions such as what BRICS will look like in a decade and what the key priorities and achievements will be. It is true that BRICS is a nascent, informal grouping and its agenda is evolving and flexible. Therein lays the uniqueness of BRICS. The BRICS leaders have reiterated that BRICS will work in a gradual, practical and incremental manner. Nonetheless, the grouping needs a long-term vision to achieve its true potential for two reasons: (1) to dove-tail the tactical and individual activities into a larger framework and direction; and (2) to help in monitoring the progress of the various sectoral initiatives in a quantifiable manner.

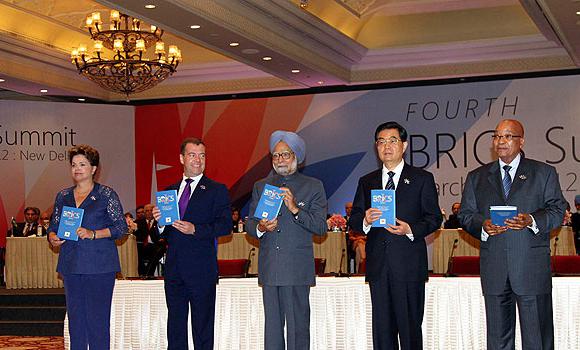

The Track II BRICS dialogue, under the chairmanship of India in 2012, has been robust. On March 4th – 6th, 2012, academics and experts from the five BRICS nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa— assembled in New Delhi for the 4th BRICS Academic Forum. The overarching theme was “Stability, Security and Growth.” This theme is useful for understanding the motivation and ethos of BRICS as a platform for dialogue and cooperation on issues of collective interest.

The dialogue led to the drafting of a comprehensive set of recommendations for BRICS leaders (Annexure 1). The 17 paragraphs that capture the recommendations to the BRICS leaders were reached through a consensual process between 60 academics and experts from the five countries. Forum delegates contributed a number of research and policy papers that formed the basis for the enriching discussions. Each of these papers highlighted key areas for cooperation, within the overall construct of the BRICS agenda. This research led to a significant build-up of knowledge on BRICS. This long-term vision document is an attempt to aggregate the dialogue and research that has fed the Track II process so far and to build upon it.

Broadly speaking, the document is divided into four sections. The first, on ‘Common Domestic Challenges’, aims to pinpoint multiple areas in which sharing experiences and best practices within the BRICS Forum will help to respond to common problems. For example, BRICS nations have vastly differing levels of educational attainment and healthcare policies. As large developing countries with significant governance challenges, but also ‘demographic dividends’ and other drivers of growth to reap, BRICS can greatly benefit from innovative ideas emanating from similarly positioned nations.

The second the matic section focuses on ‘Growing Economies, Sharing Prosperity’. Given the huge distance that the BRICS nations have yet to cover in tackling poverty and providing livelihoods to their rising populations, there is no option other than maintaining and accelerating economic growth. This section outlines the necessity of deepening intra- BRICS and worldwide trade and economic synergies. Additionally, it documents growing energy needs and discusses how the economic growth imperative affects the BRICS discourse on climate change.

The third section, titled ‘Geopolitics, Security and Reform of International Institutions’, outlines an enhanced role for BRICS within an increasingly polycentric world order. Within the United Nations (particularly the Security Council), enhanced BRICS representation can institutionalise a greater respect for state sovereignty and non-intervention. In Bretton Woods Institutions, like the IMF and World Bank, BRICS seeks to reform voting shares to reflect the evolved global system, different from that forged in the immediate aftermath of World War II. Finally, as leaders in the developing world, BRICS nations seek to create a development discourse that better represent their aspirations.

The fourth thematic section, on the ‘Other Possible Options for Cooperation’, outlines possible developments to further collective engagement once the necessary prerequisites are achieved. At the present juncture, it may be too early to think of BRICS becoming a formal, institutionalised alliance. However, it is important for the grouping to envision a commonality of purpose, continuity of operation and dialogue beyond annual summit meetings.

There are five prominent agendas of cooperation and collaboration that emerge from this vision document. These themes are integral to the very idea of long-term engagement between the BRICS nations and provide a framework for accelerating momentum and increasing significance over the long term:

1. Reform of Global Political and Economic Governance Institutions: This is the centrepiece of the BRICS agenda, which in many ways resulted in the genesis of the grouping. With the move towards a polycentric world order, BRICS nations must assume a leadership role in the global political and economic governance paradigm and seek greater equity for the developing world. Over the coming years, they must continue to exert pressure for instituting significant reforms within institutions—such as the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Various suggestions outlined in this report provide a constructive framework for enabling substantive reforms.

2. Multilateral Leverage: There are multiple formats for engagement and cooperation in order to leverage the BRICS identity at the global high table. The outcome of the BRICS officials meeting on the sidelines of the November 2012 G20 in Mexico, where it was decided to create and pool a currency reserve of up to USD 240 billion is one instance of enhanced intra-BRICS cooperation. Similarly, the Conference of Parties, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organisation are existing cooperative frameworks,

within which BRICS countries can collectively position themselves by fostering intra-BRICS consensus on issues of significance. The United Nations is central to a multilateral framework, and there is significant potential for BRICS to collaborate and assume a more prominent role in global political and economic governance, conflict resolution etc., through institutions such as the Security Council.

3. Furthering Market Integration: Global economic growth has been seriously compromised in the years following the Global Financial Crisis. Each percentage point reduction in global growth leads to a significant slowdown of economic development within BRICS which hinges upon a necessary component of economic growth. In this regard, market integration within BRICS, whether in the context of trade, foreign investments or capital markets, is a crucial step to ensure that the five countries become less dependent on cyclical trends in the global economy.

4. Intra-BRICS Development Platform: Each BRICS nation has followed a unique development trajectory. In the post-Washington Consensus era, developing economies within BRICS must set the new development agenda, which in turn must incorporate elements of inclusive growth, sustainable and equitable development, and perhaps most importantly, uplifting those at the bottom of the pyramid. The institution of BRICS-specific benchmarks and standards, as well as more calibrated collaboration on issues of common concern including the rapid pace of urbanisation and the healthcare needs of almost half the world’s population represented by BRICS, must be prioritised.

5. Sharing of Indigenous and Development Knowledge and Innovation Experiences across Key Sectors: Along with the tremendous potential for resource and technology sharing and mutual research and development efforts, coordination across key sectors—such as information technology, energy generation, and high-end manufacturing—would prove immensely beneficial for accelerating the BRICS development agenda. Moreover, the BRICS nations must share indigenous practices and experiences to learn and respond to the immense socio-economic challenges from within and outside. This vision document contains multiple suggestions for instituting such sharing mechanisms through various platforms and cooperation channels.

This document analyses the above themes in detail. Each section concludes with recommendations specific to the chapter’s theme. The final section contains synthesised suggestions which serve as an outline/framework for enhancing intra-BRICS cooperation and collaboration. The official declarations/statements of BRICS leaders are available in Annexure (s) 2 to 5.

Why BRICS is important to Brazil

Original article can be found here

Brazil has a prominent role to play in the global governance architecture. The country has sustained structural economic growth on the back of favourable demographic drivers, growing middle class consumption and broad scale socio-economic transformation. As a result, the business environment in the country has steadily improved; and the number of people living in extreme poverty have halved over the last decade. It is time for the country to place commensurate emphasis on consolidating its position as a regional leader; and as a key stakeholder on the global governance high table. BRICS provides the perfect platform to marry the dual imperatives.

Brazil boasts of one of the world’s largest domestic markets and a sophisticated business environment. It ranks 53rd on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (2001-12), and is ahead of the rest of the BRICS nations in the availability of financial services among other key indicators of financial market penetration. Brazil’s upwardly mobile middle class and its elite have inexorably embraced the liberal globalisation framework, promoted by the developed world. Consequently, since the 1990’s they have shown a greater willingness to engage with the international system, and accept transnational regulations and norms.

As a willing signatory to international norms, ranging from those around mitigation of climate change to preventing nuclear proliferation, Brazil has often broken its own historical typecast of being defensive. What superficially seems to represent a systemic re-prioritisation – requires deeper investigation. According to the Economist’s Economic Intelligence Unit, domestic savings rates in the country are below 20 percent. Mid-sized industries still largely rely on external markets for raising money and channelling investments. By default, international perception about the Brazilian economy is an important component of national strategy. Concomitantly, the Latin American identity is one that successive governments have strived to shed.

Being part of the BRICS grouping has helped Brazil to leverage its ‘emerging market’ identity and de-hyphenate from its Latin American identity (which had its own convoluted dynamics in any case). This is evident both in the global economic and political spheres. BRICS has provided Brazil with a platform to engage with the international system more progressively. It can now navigate the international rules based architecture, with greater bargaining power and seek greater representation in institutions of global economic and political governance. Using the BRICS identity, Brazil no longer has to drive a wedge between its development and growth imperatives. It can shield its poor from international regulations, without fear of its ‘investment worthiness’ being diluted. It can participate at the global high table, while simultaneously catering to nuanced regional imperatives.

The recent death of Hugo Chavez was termed “an irreparable loss” by Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff. This serves as an example of the ideological flexibility, which the country employs to engage with a neighbourhood that is strictly divided on the Venezuelan President’s legacy. Indeed fine balancing tactics are not new to Brazilian foreign policy, also termed ‘a study in ambivalence’. The pluralistic construct of BRICS fits perfectly with Brazil’s strategic outlook on its neighbourhood and the world. Brazil has taken on more regional commitments over the same twenty year period during which it has enhanced its engagements with the international system. This is evidenced from increased participation in regional working group meetings, official summits and informal gatherings by the government.

There are numerous accounts of Brazil’s deployment of regional priorities as a bargain chip. Through MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market), Brazil has been able to successfully negotiate trade agreements in favour of its national interests. It is a pivotal founder member of the five-member trading bloc, which recently included Venezuela within its fold. In the on-going negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement with the European Union (EU), Brazil has pulled out all the stops, shielding its local industries from cheaper foreign made imports; with support from other members including Argentina. Similarly, common interests rather than common ideologies dictate the BRICS agenda. Brazil’s membership of the grouping is in complete consonance with its regional and global strategic imperatives.

Aside from the adaptive flexibility that the informal BRICS grouping offers, it allows Brazil great latitude in bringing specific agendas around innovation, intellectual property rights and green growth at its core. Brazil is home to nearly half of the world’s biodiversity; the overarching sustainable development agenda is not surprisingly a national priority. Similarly, Brazil has the opportunity to use mechanisms such as the BRICS Exchange Alliance for attracting investments. While the current framework enables investors to trade in cross-listed futures indices, if there is political will, the mechanism could eventually encompass various products with different underlying assets including equities. Another relevant sector specific example is commercial aerospace cooperation, where Brazil has unmatched expertise within the grouping.

There are in fact multiple opportunities for Brazil within BRICS, not limited to the economic sphere. In many ways, the grouping brings Brazil from the left corner of the world map to the centre, where the geopolitical theatre is most active; in Asia and the Indo – Pacific. However there are two oddities in the Brazilian agenda which would require circumnavigation if Brazil is to be brought to the heart of the geopolitical discourse. The first is to moderate its insistence on pursuing ‘euro-styled’ agendas such as interventionist doctrine ‘responsibility to protect’ (R2P), with an ambiguously defined alternative ‘responsibility while protecting’. Sovereignty matters to other BRICS and there is some time before supra-national initiatives would pass muster. And the second is to shed its reluctance on the agenda for creation of a BRICS led Development Bank. In this instance Brazil, with its considerable Development Bank experience, can help shape a credible institute that will empower billions south of the equator.

Vivan Sharan is Associate Fellow and Samir Saran is Vice President at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), New Delhi.

Generosity within BRICS offers China passport to power

The original article is available here

George Orwell once remarked “Whoever is winning at the moment will always seem to be invincible.” China’s long-running growth juggernaut has resulted in a steady conversion of China skeptics into believers, so much so that a Pew Global Attitudes report released in July 2011 indicated a widespread perception that China has either replaced or will replace the US as the world’s sole superpower, with the Americans themselves just about equally divided on the subject.

For the Chinese establishment, even as being the preeminent global power remains their ultimate aspiration, China’s own outlook has been far more pragmatic.

There is a realization that the critical vectors that fuelled China’s impressive growth have either played out or are near to playing out their potential.

Exports are slowing, and the near double-digit growth in domestic consumption leaves little room for additional growth without triggering unbridled inflation.

Compounding this is fast depleting surplus labor in China’s rural backyard and steady increase in wage costs, which have grown at an annual rate of 15 percent over the past years.

This and stagnating Western demand for goods are impacting China’s growth algorithm built around the premise of inexpensive labor and competitive exports.

China’s redemption as the preeminent global power is hinged as much on its capacity to sustain its economic momentum as in its ability to influence the principles, values and rules that define global institutional mechanisms and frameworks.

However, China’s stellar economic engagement with the world has not resulted in commensurate political weight or perceptional dividends within global institutions.

To realize its aspirations, China urgently needs to find a way around this predicament, and BRICS offers it a plausible option and opportunity.

BRICS is today the most promising entente of high growth economies. BRICS’ national economic and political transformation agendas are fuelling huge domestic demand for newer types of products and services. China is uniquely positioned to gain enormously from this dispensation.

Standard Bank estimates China is party in over 85 percent of intra-BRICS trade flows, which have grown by about 1,000 percent over the last decade to over $300 billion, and are estimated to reach $500 billion by 2015.

While intra-BRICS trade accounted for close to 20 percent of BRICS’ total trade in 2012, it remains disproportionately weighed in China’s favor. Hence in any BRICS growth story, China will be the biggest net gainer.

While the BRICS nations have formed a close bond between themselves, they haven’t consummated any traditional model of interstate alliance.

The model affords sufficient space to accommodate intra-group differences and independent strains of national discourse.

It is still bilateral relationships rather than allegiance to group ethos that predominantly inform the intra-BRICS economic and political dynamic.

Group identity and collective consciousness will result from co-creating and co-managing institutions and instruments. A BRICS development bank, a stock exchange alliance and a BRICS fund are all vital next steps.

For China to unleash and benefit from the full potential of the group, it needs to work on such initiatives. These will offer it a new economic landscape and will also help take the edge out of bilateral relationships.

However, for China to command the moral weight to realize its power ambitions through BRICS, it needs to morph from a trading partner seeking profits to a strategic ally helping shape a common world.

As the partner that stands to benefit the most from any expanded BRICS play, China needs to be singularly more magnanimous and mindful in accommodating the legitimate interests and aspirations of other member states.

A disproportionate generosity, whether it is in resolving bilateral disputes or legacy issues, or, sharing of power at BRICS institutions, independent of economic contribution and effort, will reap very rich political and economic dividends, while also permanently insulating China from the politics of power imbalance within the group.

Samir Saran is vice president at Observer Research Foundation and Jaibal Naduvath is a communications professional in the Indian private sector. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

Chapter in ORF publication: “The Global Economic Meltdown”

Samir wrote one chapter in the new ORF publication “The Global Economic Meltdown”.

Please find here the original link

Please find here the full document (PDF version): Deconstructing India’s Inclusive Development Agenda

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 is widely recognized across the globe as the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression. The prolonged global economic slowdown has stymied the US economy, brought the Eurozone to the precipice, and continues to retard growth momentum throughout the world. Even developing economies that were previously thought to be crisis-averse are now experiencing the rough waters after an economic tsunami.

The writers in this compendium address the many complexities of the GFC and present a holistic overview of its background, how it unfolded and how many nations sought to respond to it. This publication is unique in its approach of the crisis from a global perspective, with pieces focusing on India, Europe and the United States. Furthermore, the book provides a thorough examination of the economic, political, environmental and social implications of the crisis and offers glimpses of the road ahead, replete with policy recommendations for a more stable and prosperous future.

Thinking the Russian Choice: BRICS v/s OECD

Please find here the link to the official publication.

After a long wait, come 2014, that most exclusive club of nations, Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) will have a new member – Russia, which at one point was its most vocal critic. With the grouping’s influence arguably on the wane, despite efforts to make it more reflective of the zeitgeist, Russia’s eagerness to join it makes for an interesting study. By itself, it may largely be emblematic of Russia’s aspirations for a slice of imagined glory on the high table of the rich. Apart from saving denizens of St Petersburg a drive across the border to Finnish supermarkets, thanks to reduction in import tariffs, it brings to the fore the dichotomies that define Russia’s foreign policy, and more notably, its unique position within the BRICS. Russia’s impending accession to OECD, will see it attempting to align to an arrangement that could be characterized ‘old world’, with attitudes to political and economic models that compete and collide with those the developing world consider optimum to their own needs. This OECD membership will be at odds with the BRICS aspiration of offering a credible alternative to extant western systems currently governing international trade and economic exchange.

Strategic Expectations

Up until the disintegration of Soviet Union, the anxious need for this ‘super-power’ to shape an equally prevailing alternative to US domination of world affairs was central to the bipolar architecture that informed world politics. While bipolarity is now a remnant of history, lingering anxieties have continued to play a visceral role in shaping Russia’s foreign policy discourse. Russia’s presence in BRICS and other multi-lateral organizations such as SCO or G-20, its play at the UN, and response to issues such as opposition to proposed NATO missile shields in erstwhile client states of Poland and Romania, can be consistently traced to this arc of alternate leadership challenging legitimating discourses of the US led Western bloc.

Russia stands at the crossroad of global power flows today, where the signboards often appear fuzzy. On the one hand, the exclusivity of OECD beckons it. Even as Russian policymakers see OECD accession as natural fit, Russia may have to remain content with a seat at the periphery of OECD policy play. Powerful, entrenched lobbies within OECD, and Russia’s own political and economic architecture, could scupper effective integration and any gains thereof. On the other hand, Russia is rightly upping her engagement ante at BRICS. Even though BRICS agenda and agency may have been shaped by characteristic developing world priorities such as urban renewal, universal health and poverty alleviation, yet it is the only capable agent on the horizon that can offer a credible political and economic alternative to extant western systems. These nations have ‘emerged’ more ‘despite’ than ‘because’ of the developed world’s hand in their own journeys of growth. Their homegrown brews of practical logic in economics and governance, which helped them over the threshold, hold valuable lessons for Russia, which needs customized rather than copybook solutions.

Economic Priorities

Russia has the highest per capita GDP in the BRICS grouping, with Brazil a close second. Viewed in isolation, this means little. However, figures have a peculiar ability to obscure reality. For, Russia’s growth is based on skewed planning logic, spindled around commodity leverage aiding wealth concentration that has created physical and economic habitations literally at the opposite ends of the spectrum, with little in the middle. So, while Russia may have one of the largest populations of billionaires on the globe, the country does not figure anywhere in the top fifteen in the world millionaires chart, even as a significant mass of people struggle to make a decent living. Even today, commodities, especially oil and gas, which contribute the biggest slice of income to the national exchequer retains high policymaking attention in the Russian schema, even as the financial sector tethers at frontier market levels with subprime level interest rates for even high quality assets. While the predictability of such economic logic is close to the Russian roulette, even its frailty exposed by oil economy collapse in the aftermath of financial meltdown of 2008, has led to little meaningful change in planning behaviors.

Russia urgently needs systemic overhaul and its BRICS calling card offers it the maximum single point leverage in this regard. Economic ethos of BRICS historically has been pivoted around creating sustainable and inclusive institutional structures, which operate with high degree of predictability, posited as counterweight to overcome the highly negotiated nature of their national agency. Dipping into this rich collective experience, especially those of Brazil, India and China, who have long perfected models of sustainable reform with emphasis on equitable wealth distribution, could significantly alter Russia’s own learning curve, delivering quicker results with much less effort and fiscal pain.

Social Priorities

With close to cent per cent literacy, healthy sex ratio, high education levels, and, almost ten hospital beds and over four physicians per thousand individuals, Russia’s social statistics rival the best in the developed world. Years of disciplined social planning by the erstwhile Soviet regime had created one of the best national social architectures anywhere. Whereas the disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the economic chaos that ensued, consumed most other national institutions, strong fundamentals anchored in robust institutional frameworks helped Russia’s social architecture negotiate adverse headwinds of over two decades or so of policy challenges and spending cuts. However this fabled resilience is now showing unmistakable signs of fracture, with income inequity, rising unemployment levels and falling living standards, all of which are making the population increasingly restive.

There is an increasing constituency within Russia’s policy-making apparatus, which realizes the long-term consequences of this trajectory. A rethinking of national priority, away from the overdependence on oil economy to improving social conditions is underway, as Russian planners realize this is perhaps the only sustainable option going forward. In this, Russia can draw and adapt from the immense experience and resource within the BRICS, especially those of post reform Brazil, India and China, where creating sustainable social architectures that balance opportunity and growth with improved living standards has been key to managing large and diverse population groups with disparate interests, and certainly with differing degrees of success.

BRICS Play

Even while BRICS will continue to make the right noises towards providing an alternative to the extant global system, its short to medium term agenda will continue to be dominated by shared domestic priorities and their interplay with global governance frameworks. For realizing their dreams of expanded geopolitical influence, member states are already operating outside the BRICS ambit, and will continue to do so. Brazil has waddled into issues in far off Middle East while China has embraced Latin America, as a single point alternative to United States. As emerging states, they are situated uniquely, being both competitors and partners at the same time. For instance, India has been romancing Japan and United States as counterbalance to China in the political play, while Brazilian policymakers are responding to China’s increasing foothold in Latin America, by establishing closer economic and political collaboration with regional states, a move away from its traditional Euro centricity.

At the same time, on the more substantive issues such as climate change, Doha rounds and WTO which hold real potential to impact the life and times of their citizens, they have functioned as a cohesive unit, even compromising stated national positions, in the finest spirit of give and take. Their development emphasis notwithstanding, BRICS agency remains sufficiently reflective of global commons, and, their interactions are witnessing an increasing play of heavy political content. BRICS have taken firm and independent positions, on the Israel-Arab conflict, Iran and Syria, broader issues of sanctions, transnational interventions and the UN system that governs peace and stability. However, BRICS are unlikely to morph into a security bloc or alliance, and neither are they likely to be anti-western in their orientation. Yet, together they have shown to be able to stand-up and take an effective position against irrational acts stemming from whimsical or partisan objectives that hold potential to disturb global stability. And, that will be the moral space BRICS will seek to occupy in global political consciousness.

Promiscuous Future

We live in a world awash with promiscuous choices. But, the high rush in such flirtation is not without matching dangers. Russia will find reasons and perhaps even the wherewithal to court both BRICS and OECD simultaneously. Even so, Russia will have to delicately balance divergent expectations of the two groups who situate themselves at different ends in an uneven spectrum.

Inclusive growth, prosperity and a stable environment (internal and external) is what each of the BRICS seek as they transform their national economic and political landscapes. While this development emphasis within the BRICS agenda (which will only increase as South Africa assumes leadership) may appear to disturb the role Russia envisaged for BRICS, and herself within it, in reality Russia stands to gain immensely from this dispensation. Considering Russia’s own urgent need for systemic overhaul, there can be no better reference point than countries at the forefront of shaping the new global order. Staying the course will also see the BRICS increase the political content of their engagement, something the Russians always sought from the group of five.

Gains from accession to the OECD, which some feel Russia is speed-gating, may yet be notional. For, reduction in tariff barriers or better access to cutting edge technologies may all be part of the solution, but by themselves, they hold little value unless fundamental changes are effected in governance and planning behaviors to release energy and vibrancy into its national system, which is incidentally the signature BRICS objective.

Jaibal Naduvath is a communication professional and Samir Saran is Vice President at theObserver Research Foundation, a premier Indian Think Tank. The article is a revised version of the column that appeared in the Russia India Report on Jan 21, 2012.

Column in SAFPI: More than just a catchy acronym: six reasons why BRICS matters

by Samir Saran and Vivan Sharan

Please find here the link to the original article.

New Delhi: There have been heated discussions over the role of BRICS recently. Ian Bremmer, President of the Eurasia Group, a political risk consulting firm, wrote an eye-catching article in the New York Times in late November, proclaiming that BRICS is nothing more than a catchy acronym. The BRICS nations represent over 43 percent of the global population that is likely to account for over 50 percent of global consumption by the middle class – those earning between $16 and $50 per day – by 2050. On the other hand, they also collectively account for around half of global poverty calculated at the World Bank’s $1.25 a day poverty line. What, then, is the mortar that unites these BRICS?

First, unlike NATO, BRICS is not posturing as a global security group; unlike ASEAN or MERCOSUR, BRICS is not an archetypal regional trading bloc; and unlike the G7, BRICS is not a conglomerate of Western economies laying bets at the global governance high table. BRICS is, instead, a 21st-century arrangement for the global managers of tomorrow.

At the end of World War II, the Atlantic countries rallied around ideological constructs in an attempt to create a peaceful global order. Now, with the shifts in economic weights, adherence to ideologies no longer determines interactions among nations.

BRICS members are aware that they must collaborate on issues of common interest rather than common ideologies in what is now a near “G-0 world,” to borrow Bremmer’s own terminology. Second, size does not matter and it never has. Interests do and they always will. Intriguingly, Bremmer expresses his concern over China being a dominant member within BRICS. Clearly, Bremmer has chosen to ignore the fact that the US accounts for about 70 percent of the total defense expenditure of NATO countries or that it contributes nearly 45 percent of the G7’s collective GDP.

Third, BRICS is a flexible group in which cooperation is based on consensus. Issues of common concern include creating more efficient markets and generating sustained growth; generating employment; facilitating access to resources and services; addressing healthcare concerns and urbanization pressures; and seeking a stable external environment not periodically punctuated with violence arising out of a whim of a country with means.

Fourth, it is useful to remember that the world is still in the middle of a serious recession emanating from the West. As Bremmer himself points out, systemic dependence on Western demand is a critical challenge for BRICS nations. Indeed, it is no surprise that they have begun to create hedges. The proposal to institute a BRICS-led Development Bank, instruments to incentivize trade and investments, as well as mechanisms to integrate financial markets and stock exchanges are a few examples.

Fifth, through the war on Iraq, some countries undermined the UN framework. The interventions in Libya reaffirmed that sovereignty is neither sacrosanct nor a universal right. While imposing significant economic costs on the world, they failed to produce the desired political outcome. By maintaining the centrality of the UN framework in international relations, BRICS is attempting to pose a counter-narrative.

Sixth, in the post-Washington Consensus era, financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank are struggling to articulate a coherent development discourse. BRICS nations are at a stage where they can collectively craft a viable alternative development agenda.

In the Fourth BRICS Summit in New Delhi in March 2012, there was clear emphasis on sharing development knowledge and further democratizing institutions of global financial governance within the cooperative framework. BRICS is a transcontinental grouping that seeks to shape the environment within which the member countries exist. While countries across the globe share a number of common interests, the order of priorities differs. Today, BRICS nations find that their order of priorities on a number of external and internal issues which affect their domestic environments is relatively similar.

BRICS is pursuing an evolving and well thought out agenda based on this premise. And unlike Bremmer, we are not convinced that they are destined to fail.

* Samir Saran is vice president and Vivan Sharan an associate fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

Article in ‘Global Times’: More than just a catchy acronym – six reasons why BRICS matters

by Samir Saran and Vivan Sharan

Please find here the link to the original article.

There have been heated discussions over the role of BRICS recently. Ian Bremmer, President of the Eurasia Group, a political risk consulting firm, wrote an eye-catching article in the New York Times in late November, proclaiming that BRICS is nothing more than a catchy acronym.

The BRICS nations represent over 43 percent of the global population that is likely to account for over 50 percent of global consumption by the middle class – those earning between $16 and $50 per day – by 2050. On the other hand, they also collectively account for around half of global poverty calculated at the World Bank’s $1.25 a day poverty line.

What, then, is the mortar that unites these BRICS?

First, unlike NATO, BRICS is not posturing as a global security group; unlike ASEAN or MERCOSUR, BRICS is not an archetypal regional trading bloc; and unlike the G7, BRICS is not a conglomerate of Western economies laying bets at the global governance high table. BRICS is, instead, a 21st-century arrangement for the global managers of tomorrow.

At the end of World War II, the Atlantic countries rallied around ideological constructs in an attempt to create a peaceful global order. Now, with the shifts in economic weights, adherence to ideologies no longer determines interactions among nations.

BRICS members are aware that they must collaborate on issues of common interest rather than common ideologies in what is now a near “G-0 world,” to borrow Bremmer’s own terminology.

Second, size does not matter and it never has. Interests do and they always will. Intriguingly, Bremmer expresses his concern over China being a dominant member within BRICS.

Clearly, Bremmer has chosen to ignore the fact that the US accounts for about 70 percent of the total defense expenditure of NATO countries or that it contributes nearly 45 percent of the G7’s collective GDP.

Third, BRICS is a flexible group in which cooperation is based on consensus. Issues of common concern include creating more efficient markets and generating sustained growth; generating employment; facilitating access to resources and services; addressing healthcare concerns and urbanization pressures; and seeking a stable external environment not periodically punctuated with violence arising out of a whim of a country with means.

Fourth, it is useful to remember that the world is still in the middle of a serious recession emanating from the West. As Bremmer himself points out, systemic dependence on Western demand is a critical challenge for BRICS nations. Indeed, it is no surprise that they have begun to create hedges. The proposal to institute a BRICS-led Development Bank, instruments to incentivize trade and investments, as well as mechanisms to integrate financial markets and stock exchanges are a few examples.

Fifth, through the war on Iraq, some countries undermined the UN framework. The interventions in Libya reaffirmed that sovereignty is neither sacrosanct nor a universal right. While imposing significant economic costs on the world, they failed to produce the desired political outcome. By maintaining the centrality of the UN framework in international relations, BRICS is attempting to pose a counter-narrative.

Sixth, in the post-Washington Consensus era, financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank are struggling to articulate a coherent development discourse. BRICS nations are at a stage where they can collectively craft a viable alternative development agenda.

In the Fourth BRICS Summit in New Delhi in March 2012, there was clear emphasis on sharing development knowledge and further democratizing institutions of global financial governance within the cooperative framework.

BRICS is a transcontinental grouping that seeks to shape the environment within which the member countries exist.

While countries across the globe share a number of common interests, the order of priorities differs. Today, BRICS nations find that their order of priorities on a number of external and internal issues which affect their domestic environments is relatively similar.

BRICS is pursuing an evolving and well thought out agenda based on this premise. And unlike Bremmer, we are not convinced that they are destined to fail.

Samir Saran is vice president and Vivan Sharan an associate fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn