Was on BBC this morning….was asked to discuss BRICS….

Ques 1 – China will dominate BRICS because of its money and might?

Ques 2 – How will India counter China at the BRICS?

Ques 3 – How can this group work together without common ideology (or something like that)?

Was at my charming best while basically saying…China will be an important player in any grouping – why only BRICS….the questions are posed incorrectly…BRICS is not a platform for India countering China….it is indeed an opportunity to take the edge of the bilateral …..and some people do not see common ideology as being necessary….(this Euro Centric fetish for “Common Humanity”) and with our individual and rich experiences we can find ways to developing pathways (unique) for an equitable and prosperous future….

Synergy and Complimentarity are the operative words and BRICS are rich with these possibilities.

For some in India as well – it is all a zero sum game….maybe it is …but they need to know the rules of arithmetic are changing and the nation state may not be the unit of measurement any more – The BRICS Stock Exchange is the business thumbs up to BRICS and the 4th Academic Forum was the “experts” support to it….many more to follow….

The skeptics can continue to earn their salaries…while we build a new platform 🙂

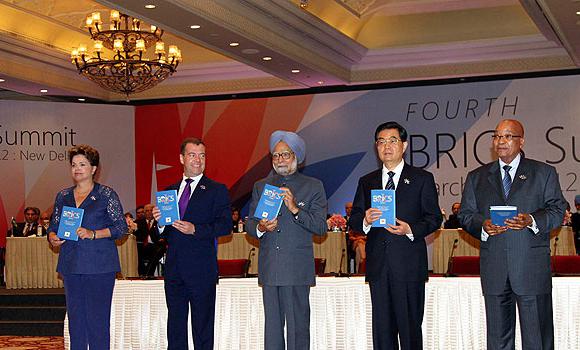

The Political will is expressed in the Delhi Declaration and it is positive, decisive and firm on what the BRICS need to do together and how they need to interact with the developed world on many common issues. I am certain that in this instance the BRICS surprised themselves …..in what they were able to agree to ….In Sanya the BRICS went wider and added South Africa….In Delhi the BRICS went deeper and added substance….

Happy BRICS Day

———————————————–

Fourth BRICS Summit – Delhi Declaration

March 29, 2012

Please find here the full version as PDF: Declaration Fourth_BRICS_Summit

1. We, the leaders of the Federative Republic of Brazil, the Russian Federation, the

Republic of India, the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of South Africa,

met in New Delhi, India, on 29 March 2012 at the Fourth BRICS Summit. Our

discussions, under the overarching theme, “BRICS Partnership for Global Stability,

Security and Prosperity”, were conducted in an atmosphere of cordiality and warmth

and inspired by a shared desire to further strengthen our partnership for common

development and take our cooperation forward on the basis of openness, solidarity,

mutual understanding and trust.

2. We met against the backdrop of developments and changes of contemporary global

and regional importance – a faltering global recovery made more complex by the

situation in the euro zone; concerns of sustainable development and climate change

which take on greater relevance as we approach the UN Conference on Sustainable

Development (Rio+20) and the Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological

Diversity being hosted in Brazil and India respectively later this year; the upcoming

G20 Summit in Mexico and the recent 8th WTO Ministerial Conference in Geneva;

and the developing political scenario in the Middle East and North Africa that we

view with increasing concern. Our deliberations today reflected our consensus to

remain engaged with the world community as we address these challenges to global

well-being and stability in a responsible and constructive manner.

3. BRICS is a platform for dialogue and cooperation amongst countries that represent

43% of the world’s population, for the promotion of peace, security and development

in a multi-polar, inter-dependent and increasingly complex, globalizing world.

Coming, as we do, from Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America, the transcontinental

dimension of our interaction adds to its value and significance.

4. We envision a future marked by global peace, economic and social progress and

enlightened scientific temper. We stand ready to work with others, developed and

developing countries together, on the basis of universally recognized norms of

international law and multilateral decision making, to deal with the challenges and the

opportunities before the world today. Strengthened representation of emerging and

developing countries in the institutions of global governance will enhance their

effectiveness in achieving this objective.

5. We are concerned over the current global economic situation. While the BRICS

recovered relatively quickly from the global crisis, growth prospects worldwide have

again got dampened by market instability especially in the euro zone. The build-up of

sovereign debt and concerns over medium to long-term fiscal adjustment in advanced

countries are creating an uncertain environment for global growth. Further, excessive

liquidity from the aggressive policy actions taken by central banks to stabilize their

domestic economies have been spilling over into emerging market economies,

fostering excessive volatility in capital flows and commodity prices. The immediate

priority at hand is to restore market confidence and get global growth back on track.

We will work with the international community to ensure international policy

coordination to maintain macroeconomic stability conducive to the healthy recovery

of the global economy.

6. We believe that it is critical for advanced economies to adopt responsible

macroeconomic and financial policies, avoid creating excessive global liquidity and

undertake structural reforms to lift growth that create jobs. We draw attention to the

risks of large and volatile cross-border capital flows being faced by the emerging

economies. We call for further international financial regulatory oversight and reform,

strengthening policy coordination and financial regulation and supervision

cooperation, and promoting the sound development of global financial markets and

banking systems.

7. In this context, we believe that the primary role of the G20 as premier forum for

international economic cooperation at this juncture is to facilitate enhanced

macroeconomic policy coordination, to enable global economic recovery and secure

financial stability, including through an improved international monetary and

financial architecture. We approach the next G20 Summit in Mexico with a

commitment to work with the Presidency, all members and the international

community to achieve positive results, consistent with national policy frameworks, to

ensure strong, sustainable and balanced growth.

8. We recognize the importance of the global financial architecture in maintaining the

stability and integrity of the global monetary and financial system. We therefore call

for a more representative international financial architecture, with an increase in the

voice and representation of developing countries and the establishment and

improvement of a just international monetary system that can serve the interests of all

countries and support the development of emerging and developing economies.

Moreover, these economies having experienced broad-based growth are now

significant contributors to global recovery.

9. We are however concerned at the slow pace of quota and governance reforms in the

IMF. We see an urgent need to implement, as agreed, the 2010 Governance and Quota

Reform before the 2012 IMF/World Bank Annual Meeting, as well as the

comprehensive review of the quota formula to better reflect economic weights and

enhance the voice and representation of emerging market and developing countries by

January 2013, followed by the completion of the next general quota review by

January 2014. This dynamic process of reform is necessary to ensure the legitimacy

and effectiveness of the Fund. We stress that the ongoing effort to increase the

lending capacity of the IMF will only be successful if there is confidence that the

entire membership of the institution is truly committed to implement the 2010 Reform

faithfully. We will work with the international community to ensure that sufficient

resources can be mobilized to the IMF in a timely manner as the Fund continues its

transition to improve governance and legitimacy. We reiterate our support for

measures to protect the voice and representation of the IMF’s poorest members.

10. We call upon the IMF to make its surveillance framework more integrated and

even-handed, noting that IMF proposals for a new integrated decision on surveillance

would be considered before the IMF Spring Meeting.

11. In the current global economic environment, we recognise that there is a pressing

need for enhancing the flow of development finance to emerging and developing

countries. We therefore call upon the World Bank to give greater priority to

mobilising resources and meeting the needs of development finance while reducing

lending costs and adopting innovative lending tools.

12. We welcome the candidatures from developing world for the position of the

President of the World Bank. We reiterate that the Heads of IMF and World Bank be

selected through an open and merit-based process. Furthermore, the new World Bank

leadership must commit to transform the Bank into a multilateral institution that truly

reflects the vision of all its members, including the governance structure that reflects

current economic and political reality. Moreover, the nature of the Bank must shift

from an institution that essentially mediates North-South cooperation to an institution

that promotes equal partnership with all countries as a way to deal with development

issues and to overcome an outdated donor- recipient dichotomy.

13. We have considered the possibility of setting up a new Development Bank for

mobilizing resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in

BRICS and other emerging economies and developing countries, to supplement the

existing efforts of multilateral and regional financial institutions for global growth and

development. We direct our Finance Ministers to examine the feasibility and viability

of such an initiative, set up a joint working group for further study, and report back to

us by the next Summit.

14. Brazil, India, China and South Africa look forward to the Russian Presidency of

G20 in 2013 and extend their cooperation.

15. Brazil, India, China and South Africa congratulate the Russian Federation on its

accession to the WTO. This makes the WTO more representative and strengthens the

rule-based multilateral trading system. We commit to working together to safeguard

this system and urge other countries to resist all forms of trade protectionism and

disguised restrictions on trade.

16. We will continue our efforts for the successful conclusion of the Doha Round,

based on the progress made and in keeping with its mandate. Towards this end, we

will explore outcomes in specific areas where progress is possible while preserving

the centrality of development and within the overall framework of the single

undertaking. We do not support plurilateral initiatives that go against the fundamental

principles of transparency, inclusiveness and multilateralism. We believe that such

initiatives not only distract members from striving for a collective outcome but also

fail to address the development deficit inherited from previous negotiating rounds.

Once the ratification process is completed, Russia intends to participate in an active

and constructive manner for a balanced outcome of the Doha Round that will help

strengthen and develop the multilateral trade system.

17. Considering UNCTAD to be the focal point in the UN system for the treatment of

trade and development issues, we intend to invest in improving its traditional

activities of consensus-building, technical cooperation and research on issues of

economic development and trade. We reiterate our willingness to actively contribute

to the achievement of a successful UNCTAD XIII, in April 2012.

18. We agree to build upon our synergies and to work together to intensify trade and

investment flows among our countries to advance our respective industrial

development and employment objectives.We welcome the outcomes of the second

Meeting of BRICS Trade Ministers held in New Delhi on 28 March 2012. We support

the regular consultations amongst our Trade Ministers and consider taking suitable

measures to facilitate further consolidation of our trade and economic ties. We

welcome the conclusion of the Master Agreement on Extending Credit Facility in

Local Currency under BRICS Interbank Cooperation Mechanism and the Multilateral

Letter of Credit Confirmation Facility Agreement between our EXIM/Development

Banks. We believe that these Agreements will serve as useful enabling instruments

for enhancing intra-BRICS trade in coming years.

19. We recognize the vital importance that stability, peace and security of the Middle

East and North Africa holds for all of us, for the international community, and above

all for the countries and their citizens themselves whose lives have been affected by

the turbulence that has erupted in the region. We wish to see these countries living in

peace and regain stability and prosperity as respected members of the global

community.

20. We agree that the period of transformation taking place in the Middle East and

North Africa should not be used as a pretext to delay resolution of lasting conflicts but

rather it should serve as an incentive to settle them, in particular the Arab-Israeli

conflict. Resolution of this and other long-standing regional issues would generally

improve the situation in the Middle East and North Africa. Thus we confirm our

commitment to achieving comprehensive, just and lasting settlement of the Arab-

Israeli conflict on the basis of the universally recognized international legal

framework including the relevant UN resolutions, the Madrid principles and the Arab

Peace Initiative. We encourage the Quartet to intensify its efforts and call for greater

involvement of the UN Security Council in search for a resolution of the Israeli-

Palestinian conflict. We also underscore the importance of direct negotiations

between the parties to reach final settlement. We call upon Palestinians and Israelis to

take constructive measures, rebuild mutual trust and create the right conditions for

restarting negotiations, while avoiding unilateral steps, in particular settlement

activity in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

21. We express our deep concern at the current situation in Syria and call for an

immediate end to all violence and violations of human rights in that country. Global

interests would best be served by dealing with the crisis through peaceful means that

encourage broad national dialogues that reflect the legitimate aspirations of all

sections of Syrian society and respect Syrian independence, territorial integrity and

sovereignty. Our objective is to facilitate a Syrian-led inclusive political process, and

we welcome the joint efforts of the United Nations and the Arab League to this end.

We encourage the Syrian government and all sections of Syrian society to

demonstrate the political will to initiate such a process, which alone can create a new

environment for peace. We welcome the appointment of Mr. Kofi Annan as the Joint

Special Envoy on the Syrian crisis and the progress made so far, and support him in

continuing to play a constructive role in bringing about the political resolution of the

crisis.

22. The situation concerning Iran cannot be allowed to escalate into conflict, the

disastrous consequences of which will be in no one’s interest. Iran has a crucial role to

play for the peaceful development and prosperity of a region of high political and

economic relevance, and we look to it to play its part as a responsible member of the

global community. We are concerned about the situation that is emerging around

Iran’s nuclear issue. We recognize Iran’s right to peaceful uses of nuclear energy

consistent with its international obligations, and support resolution of the issues

involved through political and diplomatic means and dialogue between the parties

concerned, including between the IAEA and Iran and in accordance with the

provisions of the relevant UN Security Council Resolutions.

23. Afghanistan needs time, development assistance and cooperation, preferential

access to world markets, foreign investment and a clear end-state strategy to attain

lasting peace and stability. We support the global community’s commitment to

Afghanistan, enunciated at the Bonn International Conference in December 2011, to

remain engaged over the transformation decade from 2015-2024. We affirm our

commitment to support Afghanistan’s emergence as a peaceful, stable and democratic

state, free of terrorism and extremism, and underscore the need for more effective

regional and international cooperation for the stabilisation of Afghanistan, including

by combating terrorism.

24. We extend support to the efforts aimed at combating illicit traffic in opiates

originating in Afghanistan within the framework of the Paris Pact.

25. We reiterate that there can be no justification, whatsoever, for any act of terrorism

in any form or manifestation. We reaffirm our determination to strengthen

cooperation in countering this menace and believe that the United Nations has a

central role in coordinating international action against terrorism, within the

framework of the UN Charter and in accordance with principles and norms of

international law. We emphasize the need for an early finalization of the draft of the

Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism in the UN General Assembly

and its adoption by all Member States to provide a comprehensive legal framework to

address this global scourge.

26. We express our strong commitment to multilateral diplomacy with the United

Nations playing a central role in dealing with global challenges and threats. In this

regard, we reaffirm the need for a comprehensive reform of the UN, including its

Security Council, with a view to making it more effective, efficient and representative

so that it can deal with today’s global challenges more successfully. China and Russia

reiterate the importance they attach to the status of Brazil, India and South Africa in

international affairs and support their aspiration to play a greater role in the UN.

27. We recall our close coordination in the Security Council during the year 2011, and

underscore our commitment to work together in the UN to continue our cooperation

and strengthen multilateral approaches on issues pertaining to global peace and

security in the years to come.

28. Accelerating growth and sustainable development, along with food, and energy

security, are amongst the most important challenges facing the world today, and

central to addressing economic development, eradicating poverty, combating hunger

and malnutrition in many developing countries. Creating jobs needed to improve

people’s living standards worldwide is critical. Sustainable development is also a key

element of our agenda for global recovery and investment for future growth. We owe

this responsibility to our future generations.

29. We congratulate South Africa on the successful hosting of the 17th Conference of

Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the 7th

Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol

(COP17/CMP7) in December 2011. We welcome the significant outcomes of the

Conference and are ready to work with the international community to implement its

decisions in accordance with the principles of equity and common but differentiated

responsibilities and respective capabilities.

30. We are fully committed to playing our part in the global fight against climate

change and will contribute to the global effort in dealing with climate change issues

through sustainable and inclusive growth and not by capping development. We

emphasize that developed country Parties to the UNFCCC shall provide enhanced

financial, technology and capacity building support for the preparation and

implementation of nationally appropriate mitigation actions of developing countries.

31. We believe that the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) is a

unique opportunity for the international community to renew its high-level political

commitment to supporting the overarching sustainable development framework

encompassing inclusive economic growth and development, social progress and

environment protection in accordance with the principles and provisions of the Rio

Declaration on Environment and Development, including the principle of common

but differentiated responsibilities, Agenda 21 and the Johannesburg Plan of

Implementation.

32. We consider that sustainable development should be the main paradigm in

environmental issues, as well as for economic and social strategies. We acknowledge

the relevance and focus of the main themes for the Conference namely, Green

Economy in the context of Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication

(GESDPE) as well as Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development (IFSD).

33. China, Russia, India and South Africa look forward to working with Brazil as the

host of this important Conference in June, for a successful and practical outcome.

Brazil, Russia, China and South Africa also pledge their support to working with

India as it hosts the 11th meeting of the Conference of Parties to the Convention on

Biological Diversity in October 2012 and look forward to a positive outcome. We will

continue our efforts for the implementation of the Convention and its Protocols, with

special attention to the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair

and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization, Biodiversity

Strategic Plan 2011-2020 and the Resource Mobilization Strategy.

34. We affirm that the concept of a ‘green economy’, still to be defined at Rio+20,

must be understood in the larger framework of sustainable development and poverty

eradication and is a means to achieve these fundamental and overriding priorities, not

an end in itself. National authorities must be given the flexibility and policy space to

make their own choices out of a broad menu of options and define their paths towards

sustainable development based on the country’s stage of development, national

strategies, circumstances and priorities. We resist the introduction of trade and

investment barriers in any form on the grounds of developing green economy.

35. The Millennium Development Goals remain a fundamental milestone in the

development agenda. To enable developing countries to obtain maximal results in

attaining their Millennium Development Goals by the agreed time-line of 2015, we

must ensure that growth in these countries is not affected. Any slowdown would have

serious consequences for the world economy. Attainment of the MDGs is

fundamental to ensuring inclusive, equitable and sustainable global growth and would

require continued focus on these goals even beyond 2015, entailing enhanced

financing support.

36. We attach the highest importance to economic growth that supports development

and stability in Africa, as many of these countries have not yet realised their full

economic potential. We will take our cooperation forward to support their efforts to

accelerate the diversification and modernisation of their economies. This will be

through infrastructure development, knowledge exchange and support for increased

access to technology, enhanced capacity building, and investment in human capital,

including within the framework of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development

(NEPAD).

37. We express our commitment to the alleviation of the humanitarian crisis that still

affects millions of people in the Horn of Africa and support international efforts to

this end.

38. Excessive volatility in commodity prices, particularly those for food and energy,

poses additional risks for the recovery of the world economy. Improved regulation of

the derivatives market for commodities is essential to avoid destabilizing impacts on

food and energy supplies. We believe that increased energy production capacities and

strengthened producer-consumer dialogue are important initiatives that would help in

arresting such price volatility.

39. Energy based on fossil fuels will continue to dominate the energy mix for the

foreseeable future. We will expand sourcing of clean and renewable energy, and use

of energy efficient and alternative technologies, to meet the increasing demand of our

economies and our people, and respond to climate concerns as well. In this context,

we emphasise that international cooperation in the development of safe nuclear

energy for peaceful purposes should proceed under conditions of strict observance of

relevant safety standards and requirements concerning design, construction and

operation of nuclear power plants. We stress IAEA’s essential role in the joint efforts

of the international community towards enhancing nuclear safety standards with a

view to increasing public confidence in nuclear energy as a clean, affordable, safe and

secure source of energy, vital to meeting global energy demands.

40. We have taken note of the substantive efforts made in taking intra-BRICS

cooperation forward in a number of sectors so far. We are convinced that there is a

storehouse of knowledge, know-how, capacities and best practices available in our

countries that we can share and on which we can build meaningful cooperation for the

benefit of our peoples. We have endorsed an Action Plan for the coming year with

this objective.

41. We appreciate the outcomes of the Second Meeting of BRICS Ministers of

Agriculture and Agrarian Development at Chengdu, China in October 2011. We

direct our Ministers to take this process forward with particular focus on the potential

of cooperation amongst the BRICS to contribute effectively to global food security

and nutrition through improved agriculture production and productivity, transparency

in markets and reducing excessive volatility in commodity prices, thereby making a

difference in the quality of lives of the people particularly in the developing world.

42. Most of BRICS countries face a number of similar public health challenges,

including universal access to health services, access to health technologies, including

medicines, increasing costs and the growing burden of both communicable and noncommunicable

diseases. We direct that the BRICS Health Ministers meetings, of

which the first was held in Beijing in July 2011, should henceforth be institutionalized

in order to address these common challenges in the most cost-effective, equitable and

sustainable manner.

43. We have taken note of the meeting of S&T Senior Officials in Dalian, China in

September 2011, and, in particular, the growing capacities for research and

development and innovation in our countries. We encourage this process both in

priority areas of food, pharma, health and energy as well as basic research in the

emerging inter-disciplinary fields of nanotechnology, biotechnology, advanced

materials science, etc. We encourage flow of knowledge amongst our research

institutions through joint projects, workshops and exchanges of young scientists.

44. The challenges of rapid urbanization, faced by all developing societies including

our own, are multi-dimensional in nature covering a diversity of inter-linked issues.

We direct our respective authorities to coordinate efforts and learn from best practices

and technologies available that can make a meaningful difference to our societies. We

note with appreciation the first meeting of BRICS Friendship Cities held in Sanya in

December 2011 and will take this process forward with an Urbanization and Urban

Infrastructure Forum along with the Second BRICS Friendship Cities and Local

Governments Cooperation Forum.

45. Given our growing needs for renewable energy resources as well as on energy

efficient and environmentally friendly technologies, and our complementary strengths

in these areas, we agree to exchange knowledge, know-how, technology and best

practices in these areas.

46. It gives us pleasure to release the first ever BRICS Report, coordinated by India,

with its special focus on the synergies and complementarities in our economies. We

welcome the outcomes of the cooperation among the National Statistical Institutions

of BRICS and take note that the updated edition of the BRICS Statistical Publication,

released today, serves as a useful reference on BRICS countries.

47. We express our satisfaction at the convening of the III BRICS Business Forum

and the II Financial Forum and acknowledge their role in stimulating trade relations

among our countries. In this context, we welcome the setting up of BRICS Exchange

Alliance, a joint initiative by related BRICS securities exchanges.

48. We encourage expanding the channels of communication, exchanges and peopleto-

people contact amongst the BRICS, including in the areas of youth, education,

culture, tourism and sports.

49. Brazil, Russia, China and South Africa extend their warm appreciation and sincere

gratitude to the Government and the people of India for hosting the Fourth BRICS

Summit in New Delhi.

50. Brazil, Russia, India and China thank South Africa for its offer to host the Fifth

BRICS Summit in 2013 and pledge their full support.

Delhi Action Plan

1. Meeting of BRICS Foreign Ministers on sidelines of UNGA.

2. Meetings of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors on sidelines of G20

meetings/other multilateral (WB/IMF) meetings.

3. Meeting of financial and fiscal authorities on the sidelines of WB/IMF meetings as

well as stand-alone meetings, as required.

4. Meetings of BRICS Trade Ministers on the margins of multilateral events, or standalone

meetings, as required.

5. The Third Meeting of BRICS Ministers of Agriculture, preceded by a preparatory

meeting of experts on agro-products and food security issues and the second Meeting

of Agriculture Expert Working Group.

6. Meeting of BRICS High Representatives responsible for national security.

7. The Second BRICS Senior Officials’ Meeting on S&T.

8. The First meeting of the BRICS Urbanisation Forum and the second BRICS

Friendship Cities and Local Governments Cooperation Forum in 2012 in India.

9. The Second Meeting of BRICS Health Ministers.

10. Mid-term meeting of Sous-Sherpas and Sherpas.

11. Mid-term meeting of CGETI (Contact Group on Economic and Trade Issues).

12. The Third Meeting of BRICS Competition Authorities in 2013.

13. Meeting of experts on a new Development Bank.

14. Meeting of financial authorities to follow up on the findings of the BRICS Report.

15. Consultations amongst BRICS Permanent Missions in New York, Vienna and

Geneva, as required.

16. Consultative meeting of BRICS Senior Officials on the margins of relevant

environment and climate related international fora, as necessary.

17. New Areas of Cooperation to explore:

(i) Multilateral energy cooperation within BRICS framework.

(ii) A general academic evaluation and future long-term strategy for BRICS.

(iii) BRICS Youth Policy Dialogue.

(iv) Cooperation in Population related issues.

New Delhi

March 29, 2012