El analista indio analiza en conversación con EL MUNDO la situación geopolítica actual, el impacto del auge de Pekín en el Indo-Pacífico y la estrecha relación de India con Rusia

Bisagra entre Oriente y Occidente, India es un actor de primer orden en el tablero geopolítico. Es ya el país más poblado del planeta, dispone del tercer mayor presupuesto de defensa, es una potencia nuclear y ha sabido mantener cierto equilibrio en sus alianzas con Moscú y Washington, al tiempo que refuerza su importancia estratégica en el Indo-Pacífico frente al auge de Pekín y estrecha lazos con otros países no alineados del llamado Sur Global.

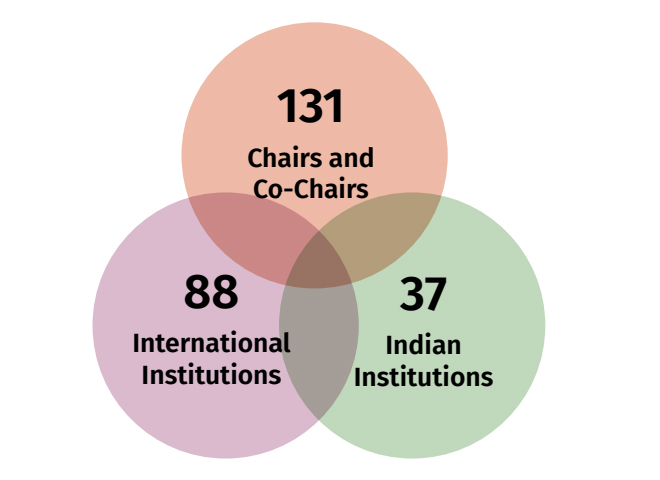

“Nos vemos como los garantes de la seguridad y la estabilidad en la región; tenemos que ser políticamente firmes para impedir que China socave no sólo la integridad soberana de India, sino también la de nuestros vecinos”. Son palabras de Samir Saran, presidente del Observer Research Foundation (ORF), comisario del Diálogo Raisina y presidente del Consejo del Secretariado Indio del T20, sobre el estado de la seguridad en el Indo-Pacífico, en conversación con EL MUNDO en Madrid, tras participar en una mesa redonda organizada por la Fundación Consejo España-India.

“Las conversaciones”, subraya, “importan ahora más que nunca”. En su calidad de comisario del Diálogo Raisina, Saran afirma que “se ha puesto demasiado de moda ‘cancelarse’ el uno al otro” cuando discrepan distintos actores geopolíticos. Por eso, tal y como advierte el analista, Nueva Delhi no se dejará atrapar entre los binarios del orden mundial actual: “India no está en el bando de nadie”.

El orden mundial actual está marcado por el tira y afloja geopolítico entre Rusia y Occidente, con el telón de fondo de la guerra en Ucrania, la creciente rivalidad sino-estadounidense y el paso del multilateralismo a la multipolaridad. ¿Qué lugar ocupa India en este tablero mundial?

A India no le gustaría ser necesariamente una de las piezas del tablero, sino más bien uno de los artífices de la partida de ajedrez. Nos gustaría ser un país con agencia política, dispuesto a asumir la responsabilidad de ayudar a diseñar y elaborar lo que surja de este periodo de turbulencias geopolíticas que usted ha esbozado, y creo que ésta es la transformación que hemos visto en las últimas décadas. Sin embargo, India es consciente de las realidades a las que todos tenemos que encarar, en concreto el paso del multilateralismo a la multipolaridad. El primero ha funcionado bien cuando ha habido una o dos superpotencias, pero aún está por probar con cinco, seis o incluso siete centros de poder diferentes. Es decir, el multilateralismo aplicado a un mundo cada vez más multipolar es un proyecto aún por emprender. Pero cuando suceda, India quiere ser uno de los países que ayuden a crear esa arquitectura de gobernanza mundial que sea capaz de acomodar esta nueva realidad de multipolaridad.

¿Y cómo se posiciona India en un mundo multipolar?

India no quiere verse atrapada entre los binarios que nos ofrece el orden mundial actual. Queremos poder forjar el camino que mejor nos convenga -que convenga al 16% de la humanidad-, el que nos permita crear un mundo que responda a las necesidades de los millones de jóvenes indios que aspiran a mejorar su calidad de vida. Por eso, considero que India se ha puesto del lado del ‘Equipo India’.

Históricamente, India se ha escudado en una postura de “no alineación” con ningún bloque, siendo ‘la amiga de todos’. ¿Es esto viable hoy?

India no tiene reparos en denunciar las acciones políticas de nadie. Que no estemos alineados no significa que seamos neutrales. El siglo pasado, nuestro país fue miembro fundador del Movimiento de Países No Alineados, que no era algo que se pretendiera valorar como algo estratégico. Se trataba de un colectivo de países que no comprometían su capacidad de decisión en función a los ‘bandos’ a los que pertenecían. Pero hoy sí es estratégico. La “no alineación” de hoy es una postura que no sólo adoptan países individuales, sino también organizaciones internacionales, como la Unión Europea. Si el mundo avanza hacia el binario de Estados Unidos frente a China, Bruselas no quiere estar ni en el bando estadounidense ni en el chino. Quiere hacer negocios con ambos, al igual que India. Y, desde luego, India no pertenece a ningún bando. Se le puede llamar “no alineación”. Se le puede llamar “multi alineación”. Incluso se le puede llamar “alineación estratégica”, pero India no está en el bando de nadie.

¿Cómo interpreta entonces la abstención india en las votaciones del Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU?

Según algunos países, como China y el Reino Unido, al abstenernos en las votaciones del Consejo de Seguridad hemos actuado contra Rusia, pero sin “alinearnos” del todo con Occidente. Pero nuestro voto no es un mensaje a Europa ni a Estados Unidos. Nuestro voto es un mensaje a Rusia: queremos que acabe la guerra.

Pero si India realmente quisiera que acabara la guerra, no se habría abstenido en la votación…

Rusia ha sido históricamente nuestro más firme defensor en el Consejo. Cada vez que se proponía una resolución adversa contra India, los rusos la vetaban. Ahora, para un país que nos ha prestado tanto apoyo en el plano internacional, una abstención india es un voto negativo que les dice que no nos estamos de acuerdo con lo que han hecho. Y pudimos hacerlo porque no pertenecemos al ‘Campo A’ ni al ‘Campo B’. Pero, ¿es esto un reflejo de nuestra relación con Rusia? Por supuesto que no, nuestra relación con Moscú va más allá de este incidente. La gente buena hace cosas terribles, las naciones honradas a veces se comportan como villanos. Pensemos en Estados Unidos en Irak. ¿Cuántos de nuestros amigos estadounidenses votaron en contra? ¿Cuántos se abstuvieron? Tal vez uno. Todos siguieron adelante con la destrucción; siguieron adelante con una clara violación de todos los principios del derecho internacional y de las normas internacionales porque a veces los buenos países tienen un momento de locura. Pero no ‘cancelamos’ a Estados Unidos, no dejamos de hablar con ellos por lo que hicieron. Por eso, hay que entender que nuestra relación con Rusia precede a la guerra. Es mayor que el conflicto.

¿Y la relación con Rusia por el gas?

Cada Estado tiene que cuidar de su pueblo, por eso todos han mantenido relaciones con Moscú en el sector energético. No se puede culpar a los indios por comprar energía a un país al que también se la compran. La energía no es un quid pro quo. La energía no influye en mi voto en la ONU. Es una mercancía que busco. Y, por cierto, hay que dar las gracias a India. Si no compráramos nuestra energía a Rusia, los precios del petróleo se habrían disparado. Hemos hecho un servicio al resto del mundo al poder adquirirlo, refinarlo y devolvérselo para que sus coches funcionen. Al fin y al cabo, los mercados energéticos son eso: mercados. No son acuerdos gubernamentales ni tratados. Se basan en los principios de precio, acceso, demanda y oferta. A eso es a lo que hemos respondido.

India asumió la presidencia del G20 el pasado diciembre bajo el lema ‘El mundo es una sola familia’. Sin embargo, en la reunión de ministros de Asuntos Exteriores celebrada en marzo en Nueva Delhi, el titular indio no logró convencer a EEUU, Rusia y China para que emitieran una declaración conjunta sobre la guerra. ¿A qué retos se enfrenta India en lo que queda de mandato?

El mundo debería alegrarse de que el año pasado fuera Indonesia quien estuviera al frente del G20, y que este año sea India y el siguiente Brasil. Esta troika de países en desarrollo garantizará que el foro no muera. Si alguno de los miembros europeos hubiera estado al mando cuando estalló la guerra, el G20 se habría convertido sin duda en G19, G18 o incluso G17. Así que, si el foro sigue siendo solvente, será algo que estas presidencias, que casualmente están alineadas juntas, habrán conseguido. Por tanto, uno de los principales objetivos es garantizar que el G20 continúe como idea, como grupo, como foro para resolver algunos de los problemas más cruciales que se han visto eclipsados por la invasión rusa de Ucrania. Aunque no hubo una declaración conjunta, lo que sí conseguimos fue una declaración de efectos acordada entre todos los miembros. Pero si queremos ser ambiciosos en la búsqueda de soluciones tangibles sobre el clima, la tecnología y otras cuestiones financieras, tenemos que encontrar una respuesta a los dos párrafos sobre los que no llegamos a un consenso. De lo contrario, tenemos que ser lo suficientemente astutos como para darnos cuenta de que quizá necesitemos idear un nuevo formato para la resolución de conflictos, en el que tengamos un conjunto de tareas acordadas que llevar adelante y una secuencia de análisis divergentes de la situación política actual, que también podamos hacer constar, estemos de acuerdo o no.

Pekín no sólo compite por la hegemonía mundial frente a Washington, sino también por el control del Indo-Pacífico, donde India ha reivindicado su papel como proveedor de seguridad. ¿Qué percepción tiene de China?

Hace tres años, en una entrevista para un periódico indio, dije que China era a la vez un país moderno y medieval, una especie de Reino Medio, por así decirlo. Es moderno porque su patrimonio es fruto del auge de la tecnología, la fabricación y las cadenas de suministro. Sigue creyendo que es el Reino Medio y que el mundo debería girar a su alrededor, pero su mentalidad es medieval. Cree en el control estatal sobre la innovación, las empresas y sus ciudadanos. Y esa seguiría siendo una valoración justa de China hoy, tres años después. No he cambiado de opinión.

¿Es posible el diálogo con China?

China sueña con un mundo en el que sea uno de los principales centros de poder, y el único en Asia y el Indo-Pacífico, un modelo de unipolaridad que India rechaza tajantemente. Hay que impedir que China socave la integridad soberana india, pero no podemos desear que desaparezca. Tenemos que sacar músculo político para hacer frente a sus amenazas. Tenemos que desarrollar una fuerte capacidad militar para impedir que se aventuren en nuestro territorio. Pero, sobre todo, tenemos que mantener un diálogo sensato con Pekín: ha de ser una condición previa para una coexistencia sostenible.

¿Qué importancia tiene la alianza Quad para las relaciones estratégicas de India en el Indo-Pacífico?

Se subestima el impacto de esta alianza. Somos cuatro países muy distintos, cada uno con un planteamiento distinto de la política interior y exterior, pero aun así compartimos la misma valoración del balance de poder del Indo-Pacífico: China está alterando la paz. Y hemos sabido dejar de lado nuestras diferencias para tratar de contrarrestar el auge de Pekín en la región. Al manifestarse así estos cuatro actores, el Quad se ha convertido en el catalizador del surgimiento de otras agrupaciones, como AUKUS, que tratan de impulsar mecanismos de gobernanza regional. Para nosotros, el Quad representa la confirmación de un Indo-Pacífico multipolar que no está dispuesto a dejarse moldear por el modelo de unipolaridad que China ofrece.

¿El Quad busca competir directamente con China o pretende entablar relaciones y cooperar con ella?

Si consideramos los países que componen el Quad y sus respectivos acuerdos comerciales bilaterales con China, podemos ver que cada uno de ellos tiene a China entre sus tres o cuatro principales socios comerciales. Así pues, estos cuatro países son actores geopolíticos que son capaces de tomar decisiones racionales: no quieren ‘cancelar’ a China, pero tampoco van a dejarse intimidar por ella. Estas son las bases de compromiso que se han puesto sobre la mesa.

Source : July 13, 2023, EL MUNDO

https://www.elmundo.es/internacional/2023/07/13/6423317efdddff46058b45be.html