Co-authored with Dr. Alexis Crow

Some commentators have trumpeted the “end” of globalization in the wake of rising protectionism over the last half decade, the sudden economic stops wrought by COVID-19, and the corollary disruptions of supply chain activity around the world.

The truth, though, is that for companies and investors involved in the exchange, transmission, and sale of goods, services, technology and finance, globalization is anything but dead. Granted, the landscape has dramatically shifted since the 1990s, and executives will need to be nimble and agile in navigating the new environment, which is currently in a state of flux.

Indeed, more recent developments in the global trade environment including green frameworks, digital protocols and regional partnerships offer a glimpse not of the demise of globalization, but rather, of what global trade may look like in the post-COVID-19 era.

Globalization and its “discontents”

Globalization is defined as the process by which technology and the information and communication technology (ICT) revolution of the 1990s enabled faster transaction times and processes for exchanges of currency, capital, information, innovation, goods and people around the world.

These transmissions of commerce have been facilitated by norms, laws, regimes and treaties governing trade, such as the World Trade Organization at the global level and agreements such as ASEAN at the regional level. At a national level, the creation of free-trade zones further facilitated the ease of trade: for example, a shipping container can move through a seamless logistics corridor in the United Arab Emirates from the Port of Jebel Ali to the Dubai International Airport within four hours.

In financial services, hubs such as the City of London and latterly Singapore have attracted leading talent from across the globe to investment banking, trading, fintech and asset and wealth management, with executives and their teams using these hubs to penetrate the “spokes” of business in the EMEA (Europe, Middle East, Africa) and south/southeast Asian regions.

Unfortunately, the very same global interconnectedness that facilitated wealth creation and economic opportunities also had a dark side that manifested throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Global and transnational risks such as international terrorism (such as the attacks of 9/11), environmental degradation, cyber-attacks, pandemics, human trafficking and financial instability and financial crises ricocheted across the globe. Such risks might pop up in one jurisdiction and by the very same conduits that fostered the “bright side” of globalization easily spread across geographies.

Today, we might say we are dealing with a different shade of discontent within societies— particularly pronounced within advanced economies—for which the process of globalization is often blamed: rising domestic income inequality. While global trade has lifted billions of people out of poverty and sharply reduced inequality at a global level (such as that between China and the West, and southeast Asia and the West), income, wealth and opportunity inequality have been steadily rising within countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Italy. Clearly, the benefits of globalization have not been shared by all. Yet, the globalization of labour markets is but one of a number of contributing factor to rising inequality within these societies since the 1980s.

Nevertheless, some leaders have found it both palatable as well as politically convenient to point the finger of blame at other countries. Rising income generation and economic advancement in Japan, for example, became a target of ire within certain circles in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. More recently, some activist politicians and commentators have pointed to the economic gains made by certain groups (such as immigrant workers) as a clear causal factor for the erosion of the domestic middle class.

Rising economic nativism has taken various forms within the last few years and has in some cases been accelerated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless of the underlying causes of domestic inequality and social anxiety, politicians have acted out against trade in the following ways:

- Ructions against goods. In recent years, some countries have focused on the balance of trade in goods (or the imbalance) as a way to reduce imports or to onshore production. Tariffs became the policy tool of choice as a way of addressing such imbalances, but when implemented, have had mixed results. Data shows that efforts to boost domestic production of goods and services comes at a cost: quite literally, for the governments, companies and consumers.

- Restrictions on mobility. Responses to the angst felt against global trade have not been limited to goods or volume of merchandise. States have also moved to restrict immigration, vowing to protect domestic workers from a perceived disadvantage. It is important to note that curtailing mobility also comes at a cost—during COVID-19 restrictions, a sharp reduction in migrant agricultural workers within OECD countries has contributed to a sharp rise in food prices, which have reached a six year high.

- Tech bifurcation. Although countries, companies and individuals are importing and exporting more services than ever before, a bifurcation has developed between the United States and China regarding certain aspects of trade in technology. Indeed, the situation has been referred to this as a “technological Cold War” between the “two greatest powers” in the world.

While some European countries have also passed legislation to restrict inbound investment in specific targets or sectors, the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI)—signed at the end of 2020—was designed to improve laws and practices for mutual investment between China and the EU, at a federal level. Although currently on hold, the negotiations did demonstrate a willingness for both sides to convene in order to potentially step up the level of investments within their respective economies.

Three emerging paths forward

Within a turbulent geopolitical context, the shape of a post-COVID-19 trade landscape is becoming clearer, particularly regarding the digital, green and regional spaces.

- The digital realm

A multilateral framework is… the need of the hour to avoid any more trade wars that the pandemic-stricken world economy cannot bear.

Data protection and securing user privacy in the digitized world has been a major issue of cross-border friction. But here we are seeing concrete efforts being made. To this end, the EU General Data Protection has offered a common template that has even inspired the California Consumer Privacy Act.

This is not to say that all contentious issues have been resolved. One complicated issue has been the taxation of digital services. Although there has been an attempt by the OECD to devise a framework for digital taxation, a multilateral solution has not evolved so far. Against this backdrop, the United Kingdom, France, India and Italy among other countries have started levying taxation on digital services, with the United States taking subsequent action under Section 301 of its trade law. A multilateral framework is, therefore, the need of the hour to avoid any more trade wars that the pandemic-stricken world economy cannot bear.

The fact that there is some early convergence on contentious issues is a positive dynamic and suggests that even though an overarching framework governing the digital realm is elusive so far, consumer interest will be the guiding force in determining the nature of regulation.

- The green space

Increasingly, at least in the developed world, “going green” is the new industrial and growth strategy.

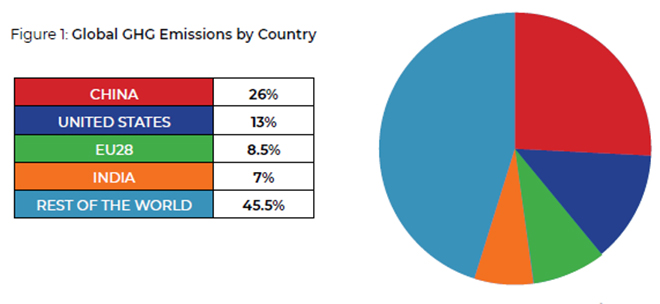

Climate action is the base on which economic policies of the twenty-first century are likely to be formulated—increasingly, at least in the developed world, “going green” is the new industrial and growth strategy.

To be sure, there are challenges. Recent discussions on the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, essentially an emissions-related import tariff, are the first sign of movement towards a global “carbon club”, shutting out exports from countries that may not comply. But the current moment presents a historical opportunity for cooperation. As climate commitments strengthen across the globe, economies of scale have led to rapidly falling costs for green energy and technology.

- A region-based approach

As efforts are underway at reforming the global trading system, regional or bilateral agreements are helpful in providing building blocks for greater cohesion.

While many Western countries have been contending with populist movements in the years leading up to COVID-19, and then resurgent strokes of economic nativism in the wake the pandemic, countries in Asia signed the largest trade agreement in history—the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2020.

Effectively, RCEP incorporates some rich income Asian countries within the ASEAN community; and in a historic step, it is the first framework to include China, Japan and South Korea together within a trade agreement. While some commentators argue that RCEP is less comprehensive than other deals such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, the convening of RCEP signatories signals Asia’s continued commitment to connect “multiple factory floors” at a regional as well as a global level.

The cementing of RCEP—with the participation of some of the fastest growing economies in the world—raises the question: do regional trade agreements help or hinder the global trading landscape? With variegated standards on data privacy, green and carbon, and with countries at various stages of economic growth and employment, a global architecture might be elusive. It can therefore be argued that as efforts are underway at reforming the global trading system, regional or bilateral agreements are helpful in providing building blocks for greater cohesion.

Reaping the benefits of a global division of labour and capital

Even though the global trading architecture has taken severe knocks from both populism and the pandemic, nearly one-third of the world’s population and one-third of global GDP have recently been incorporated in a historic trade agreement.

And even amidst the “great lockdown” of 2020, the contraction of global trade in goods was less than half of that of the trough of 2009, in the wake of the global financial crisis. Moreover, an asynchronous regional recovery from COVID-19 has meant that many companies have been able to make up for the loss demand in one region (such as Europe) by the growth in demand in another region (such as China). And uneven sectoral activity, such as the working-from-home dynamic, is propelling demand for critical goods such as semiconductor chips, which is propping up export markets for countries such as South Korea. The growth of the electric vehicle industry and the commitments by governments to “build back greener” are also contributing to cross-border flows of metals and materials.

Nevertheless, as policy-makers set their priorities on rebuilding their societies, the lure—or mystique—of self-sufficiency remains strong. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe losses to income for both advanced as well as emerging economies—the former experiencing a loss of 11% of income of 2019 levels, and the latter nearly double, at 20%. Yet, the way out of economic desolation is not via isolation, or constructing a fortress nation.

The way out of economic desolation is not via isolation, or constructing a fortress nation.

The way out of economic desolation is not via isolation, or constructing a fortress nation.

Laudably, within some advanced economies, COVID-19 relief measures have catalyzed the implementation of policies, including those designed to address housing affordability and access to childcare, that are meant to combat systemic income inequality. As countries transition from relief to recovery, and policy-makers weigh up prospects for bolstering domestic employment, it goes without saying that demand for many jobs within tradeable services is implicitly connected with the viability of export markets.

Thus, the ability to underpin and renew export ties with dialogue—such as that recently conducted between the US and the EU—is integral to sustainable domestic growth. Additionally, in the realm of non-tradable services, creative policies to incentivize corporate and private investment in reskilling, upskilling and learning for working are absolutely critical – in essence, segueing from investing in fixed capital to human capital. Amplifying competitiveness and improving productivity in both tradable and non-tradable sectors can also be enhanced by infrastructure spending and investment, in hard and soft sectors.

In the realm of non-tradable services, creative policies to incentivize corporate and private investment in reskilling, upskilling and learning for working are absolutely critical – in essence, segueing from investing in fixed capital to human capital.

In the realm of non-tradable services, creative policies to incentivize corporate and private investment in reskilling, upskilling and learning for working are absolutely critical – in essence, segueing from investing in fixed capital to human capital.

As countries increase investment in non-defense related R&D in sectors such as biotech and electric transport, it is important to consider that innovation is implicitly tied to immigration. In the United States, this has been the case throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and with immigration as one causal factor of the blossoming of cutting-edge technology businesses and the growth of entrepreneurship in the country. Thus, data shows that the vitality of human capital is inherently cross-border and reliant on immigration. Recognizing this is a requisite component of any industrial, or rather, post-industrial policy, for advanced economies and for emerging and developing economies that are shifting from old to new economic growth.

Originally published https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/05/the-global-trade-map-after-covid-19-from-fixed-capital-to-human-capital/