As we approach the third decade of the 21st century, it is unmistakable that Asia now has a twin – Africa. Even as economists and political pundits alike contest and celebrate the Asian Century, it would be erroneous to ignore the promise that a full one-fifth of humanity that is young, aspirational and innovative holds.

Africa is unarguably already the new growth engine of the world. It is now at the vanguard of tackling the most fundamental development challenges of our time—from lifting millions out of poverty in an increasingly fossil fuel constrained world, to creating new enterprises and opportunities for a young and aspirational workforce. And like Asia, Africa is home to the youngest and fastest growing economies. It is evident that the rise and the leadership of these twin geographies will define global growth and prosperity. The Afro-Asian century is indeed upon us.

Africa has taken command of its own destiny at a time when the global balance of power is irrevocably shifting. These global transformations will create new opportunities to forge beneficial coalitions and partnerships. The troika comprising of the UK, India and Africa must use this moment to carve a new relationship and cement an old accord. The UK, for one, seeks new purpose: finding its place in the world outside the confines of the European Union. “Global Britain” is now its new agenda. Simultaneously, India’s footprint has moved beyond South Asia and the Indian Ocean, and its aspirations and hunger for partnerships necessitate a recalibration of its engagement with Africa. A realisation has dawned on Raisina Hill that India’s partnership with the continent will determine its economic prosperity and national security.

The convergence of interests between the communities, markets and states of Africa, the UK and India will script the entwined futures of the three geographies.

A convergence of Interests

Trade expansion, responding to climate change, and technology-led growth are the areas where the interests and stated ambitions of all three geographies converge.

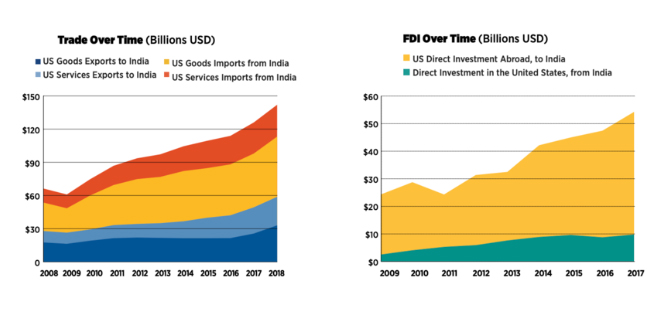

Africa has emerged as a trading giant, with significant implications for the global arrangements. The African Continental Free Trade (AfCFTA), which came into effect on 30 May, has created one of the world’s largest free trade zones. It has brought together the commercial potential of a billion individuals —with the AfCFTA now valued at over $2 trillion. London, meanwhile, remains the financial capital of the world, despite the looming shadow of Brexit. India, for its part, is already contributing to 15 per cent of global GDP growth—and its share will only get larger. As Africa shapes new trade arrangements, India pushes for reform at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and Britain searches for new partners, all three geographies can discover solutions and pathways to their ambitions in the other.

Beyond trade, sustainability forms the core of their respective development agendas, and all three regions are at the forefront of combating climate change. The UK continues to lead the Atlantic green transition, with the potential to reach near-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. India is responding with its own propositions. Home to the International Solar Alliance, it is currently the second largest solar power market in the world. The upward revision of its solar capacity target for 2022 from 20 GW to 175 GW speaks to the success of India’s efforts. As Britain and India discover solutions and pathways for sustainable growth, Africa has a hunger that the two satisfy. Energy poverty costs the continent two to four GDP percentage points per year, and Africa needs innovative solutions to meet the energy demands of the 600 million people who remain off-grid. A partnership between the three geographies has the potential to cater to the energy and development demands of this large cohort of the human population.

Finally, all three seek to leverage the technologies of the 4IR to create economic opportunity and pathways for social mobility. Enterprises in the Fourth Industrial Revolution will be driven by the energy of the young. With its mature regulatory ecosystem, Britain can supply the services and the institutions that cater to start-ups and gig economy; while India and Africa, powered by ideas and the human zeal, can provide solutions that truly cater to the bottom of the pyramid and export solutions to the developed world as well. This presents us with a unique opportunity to co-design policy in an age of disruption and to address some of the most pertinent challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution—harnessing women’s potential and providing protections (social and physical), purpose and paychecks.

New Economic Diplomacy

At a time when challenges transcend state boundaries, building multi-stakeholder partnerships and responses is crucial. ORF is excited to help catalyse new conversations across these three geographies through the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED). The CNED is a policy research platform committed to building communities and strengthening transnational partnerships to respond to challenges and opportunities that confront the global community. Over the past six months, the Centre has successfully curated platforms to facilitate the cross-pollination of ideas, debates and solutions across geographies. On the sidelines of the United Nations Environment Assembly, the CNED hosted the first India and Africa Partnership for Sustainability conference in Nairobi, Kenya. This platform brought together over 40 stakeholders from over 11 countries to coordinate responses to climate change and the broader SDG agenda. Following its success, CNED launched the Global Programme for Women’s leadership in New Delhi, a seven-day programme that brought together over 100 young women from India, Africa and the Bay of Bengal communities in an effort to build a trans-continental network of future leaders.

A conciliation with history

The CNED is not merely a community of experts. It is an effort that seeks to capture the realities that will define global growth in the decades to come. The traditional North-South and East-West divides are remnants of days past, which were harsh, brutal and inequitable. The success and failure of international regimes, global governance, and globalisation itself have been implicated by these conceptualisations. Escaping these realities requires embracing new relationships that are driven by mutual respect and collaboration—in formats that discard the geographical constructs of the 20th century. An India-UK-Africa relationship possesses the strongest potential to catalyse a new arrangement and perhaps a new global ethic—one that allows us to leapfrog old limitations. This is a poignant partnership, which will help shed artificial distinctions constructed by human greed and allow these three vital regions to contribute to a new world order.

We are delighted to collaborate with the India-UK week to bring our partners from Africa and India to help shape and redefine the most important trilateral engagement of our time.