Author Archives: Dr. Samir Saran

Reclaiming the storied legacy of the Arabian Sea

APM Modi and Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed are putting in place the building blocks for a prosperous Arabian Sea community

Post-Independence, India has been unfair to the sea that laps against our western shoreline. We forget that the Arabian Sea has long been a fertile bridge for the exchange of ideas, stories, commerce, and culture. Khazanas of knowledge have flowed through its waters and lasting friendships have been forged. More than any Indian Prime Minister (PM) before him, Narendra Modi recognises the injustice of this neglect. His upcoming visit to Abu Dhabi will be his seventh — six more than any predecessor. Before his first trip in 2015, no Indian PM had set foot in the Emirates for over three decades.

While numbers are often inconsequential, sometimes they do matter. As the B-school adage goes: If you can’t count it, it doesn’t count. Seven prime ministerial visits paint a picture. It signifies a change in the relationship and a growing appreciation of each other’s importance. What India and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have built is a special affinity. It reflects a new reality, one where the India-UAE bond is no longer voluntary but mandatory, not a choice but an instinct. PM Modi and Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan have undertaken a systematic overhaul: We are now mutually indispensable.

At the same time, he is attending the World Government Summit, a platform for deliberating innovation to deal with emerging governance challenges.

The very texture of this relationship is different. PM Modi is travelling to inaugurate the first Hindu temple in the UAE, an exemplar of Abu Dhabi’s promotion of a more pluralistic society. At the same time, he is attending the World Government Summit, a platform for deliberating innovation to deal with emerging governance challenges. In tandem, these act as a synecdoche for the larger relationship: The two nations are partnering with each other while celebrating who they are. They seek to be part of each other’s change while not seeking to change the other. India has friendly relations with many nations, and yet such friendships often come with prescriptive clauses of what India can or cannot do; of what India should or should not be. A large part of why the India UAE relationship is special is because it is descriptive, not prescriptive.

Embedded deeply in the India-UAE bond is a celebration of each other for what we are — plural yet singular. Plural because of our diversity of cultures and customs, and the heterogeneity inherent in our nations. Singular because we have navigated uncharted territory, and plotted an unmapped path for ourselves. In their own unique ways, both countries are exceptions in the region and in today’s times. The UAE has created a lush economy in the middle of an arid desert. India’s specific development challenges have no parallels, with individual states the size of entire nations. For both of our countries, there have been no models to follow, no moulds to fit into. This is the foundation of our mutual respect. It will continue to be the bedrock of our relationship as we transform incomes, update infrastructure, and move from an analogue to a digital world.

Diaspora lies at the centre of our relationship. More than 60,000 Indians have signed up to attend the PM’s address at the Zayed Sports City Stadium. However, statistics of this sort do not do true justice to the real story of the Indian diaspora in the UAE. The fact is Indians today share the top floor of skyscrapers in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Positions that by default went to Europeans and Americans, today, see a large proliferation of Indians, whether in finance, energy, or infrastructure. They are being recognised as valued advisors, creative talents, and financial wizards, rubbing shoulders with Emiratis in building a 21st-century nation and contributing to the future of the UAE. This cohort of Emiratis and Indians is working to make the UAE a global hub for our century, even as they make India a global economic powerhouse for the benefit of the country, the region, and humankind at large.

Positions that by default went to Europeans and Americans, today, see a large proliferation of Indians, whether in finance, energy, or infrastructure.

As China rose, a small clique of cities benefitted: Hong Kong, Singapore, London, and New York. India’s journey, from four trillion dollars to 30, will see the world benefit. Abu Dhabi and Dubai will hold a privileged position in this odyssey. Even as India benefits, so will the global ambitions of the UAE. Moving forward, the UAE will be the new Gateway to India. It will be a talent hub, connecting Indian opportunities and Indian talent with the rest of the world. It will be a trade hub, with goods — and energy — that flow to and from India passing through it. It will be a finance hub, where it will be able to source at scale the capital required to sate India’s growing appetite.

PM Modi and Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed are putting in place the building blocks for a prosperous Arabian Sea community. They are restoring the sea to the storied position it held in antiquity, refreshing it and bringing it into the 21st century. This community will offer people-centric, development-first, and growth-led solutions for Africa, Europe, and the Indo-Pacific. The space between the Gulf and the subcontinent will reclaim its role as the wellspring of inclusive globalisation in this century, just as it was millennia ago.

This article appeared originally in Hindustan Times.

Creating a Climate-Friendly Investment Climate

Abstract

More investment is needed to achieve the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement. This Policy Brief suggests that the solution lies in increasing climate FDI—cross-border investment aligned with climate goals—by creating a ‘climate-friendly investment climate’. The authors recommend four targeted measures, drawing from a new ‘Guidebook on Facilitating Climate FDI’, to be published by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with Wavteq/fDi Intelligence: (1) Align investment promotion agency (IPA) strategies, key performance indicators (KPIs), incentives and de-risking instruments to climate goals; (2) Create a database of sustainable suppliers and a supplier development program to help domestic firms become sustainable; (3) Map multinational enterprise climate commitments and create a pipeline of endorsed and vetted carbon-neutral investment projects that help MNEs deliver on their commitments; and (4) Include climate FDI provisions in international investment agreements and national legal frameworks. Finally, a Coalition of IPAs for Climate is proposed to increase knowledge, facilitate cooperation, and drive action to increase climate FDI. The Coalition can use the measures to help facilitate two-way climate FDI between G20 economies, resulting in mutually beneficial outcomes.

1. The Challenge

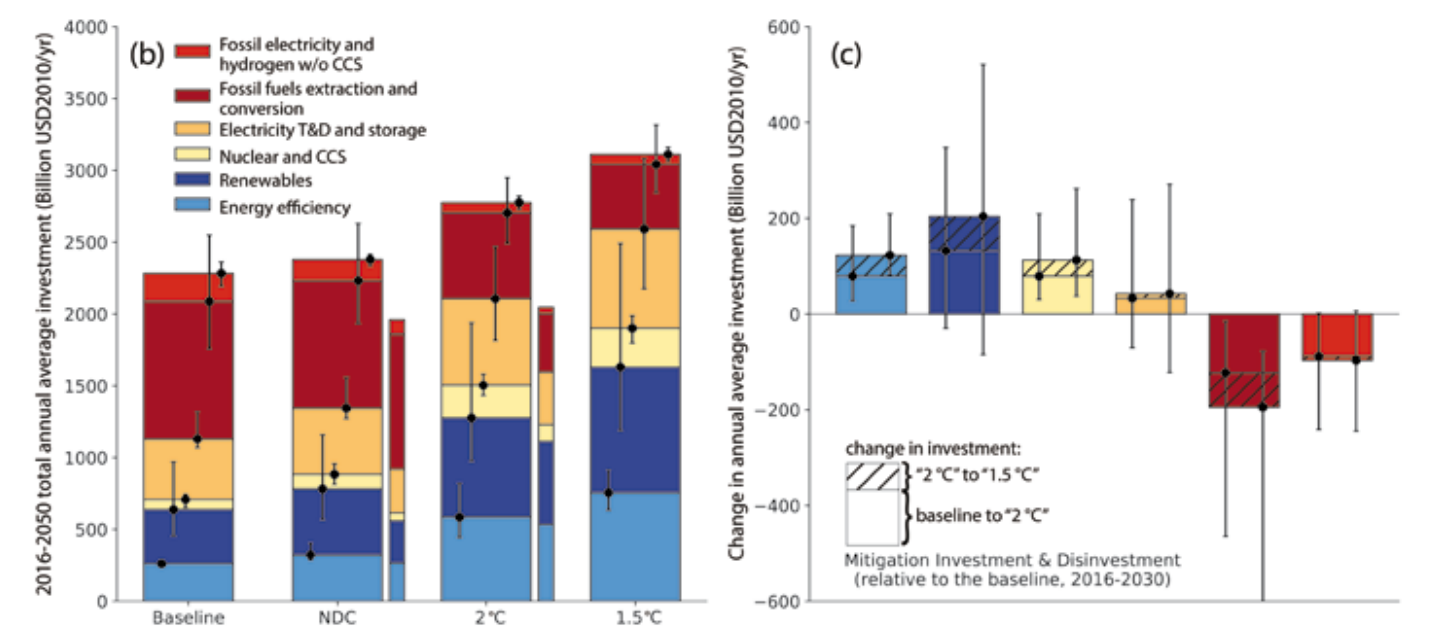

According to IPCC estimates, about US$800 billion in new investment in energy systems is required each year between 2012 and 2050, to reach the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C (de Coninck et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 361). This is in addition to current investment trends. Estimates place the baseline investment in energy systems at US$2.38 trillion of yearly investments, compared to the US$3.2 trillion that is needed (de Coninck et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 321).

Figure 1. Historical and Projected Global Energy Investments in Different Scenarios (2016-2050)

Note: The left figure uses six global models to represent four different scenarios: investment in energy systems that continue along the current baseline (i.e., pathway without new climate policies and measures beyond those already in place), increasing investment to achieve nationally determined contributions (NDCs), increasing investment to keep global warming to 2°C, and increasing investment to keep global warming to 1.5°C. The bars represent the model means, while the whiskers the full model range. The right figure represents the needed change in investment to keep global warming at 2°C or 1.5°C relative to the baseline. Whiskers show the full range around the multi-model means.

Source: Rogelj et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 155

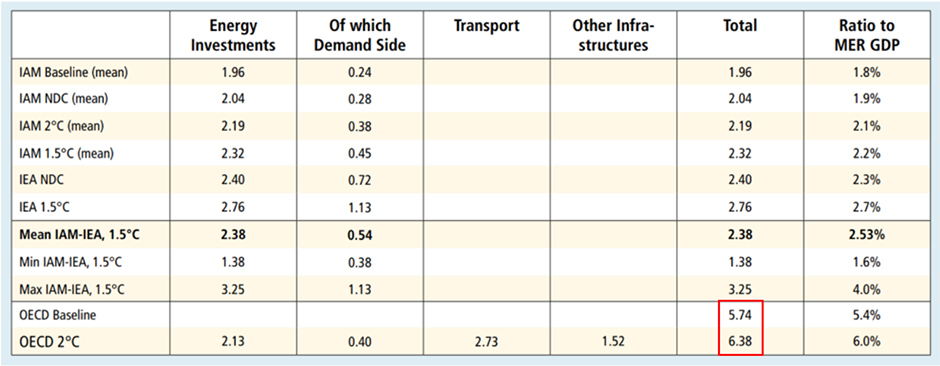

What about beyond energy systems? Earlier OECD estimates place the total investment needed at around US$6 trillion (see Figure 2, red box). These are astoundingly large figures.

Figure 2. Energy Investments Vs Other Investments for Climate Goals (2015–2035)

Note: Estimated annual world mitigation investment needed to limit global warming to 2°C or 1.5°C (2015–2035 in trillions of USD at market exchange rates).

Source: de Coninck et al. 2018 in IPCC 2022, p. 373

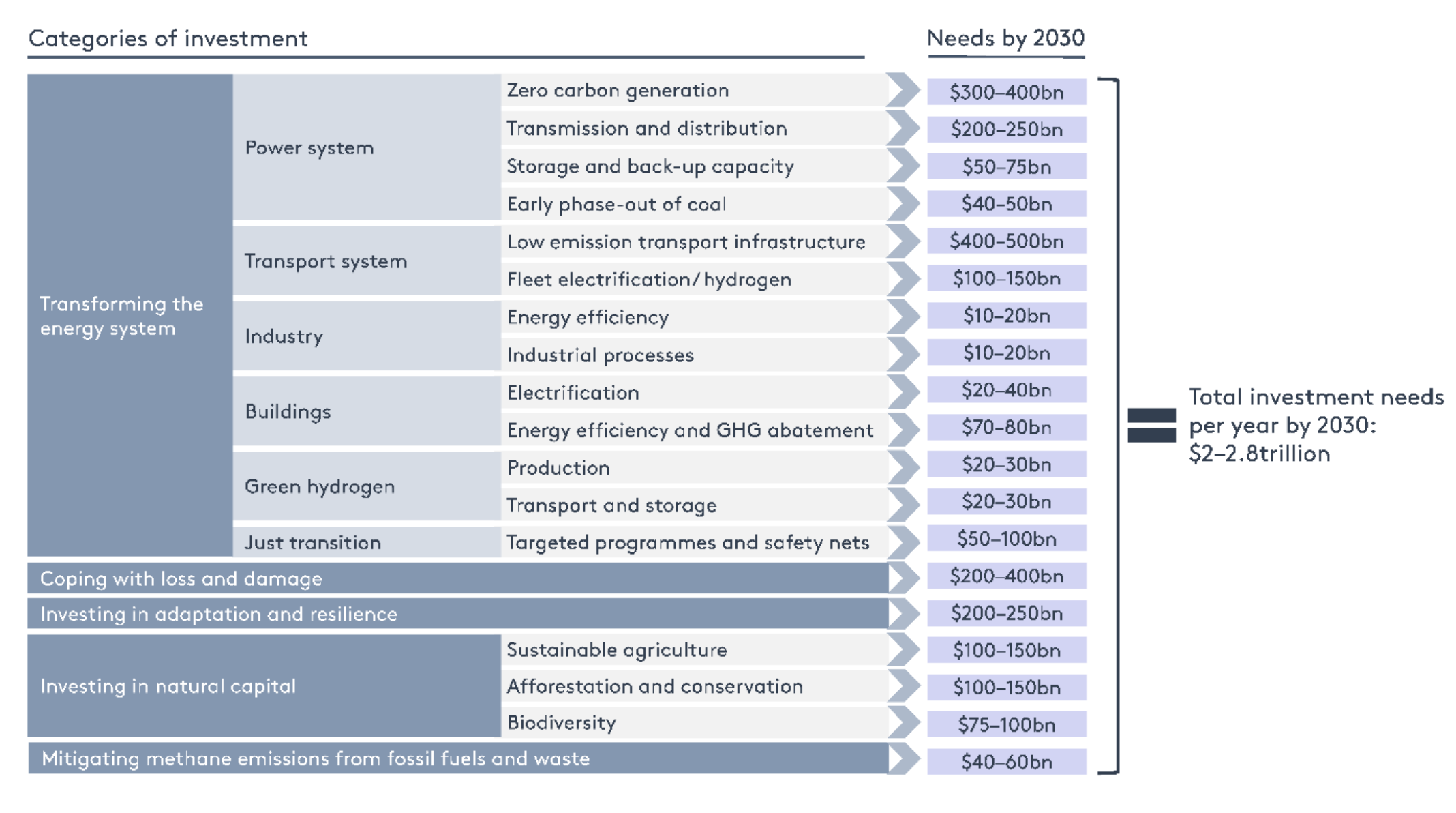

More recent estimates suggest that between US$2 and US$2.8 trillion in investment may be needed every year to reach climate goals (Songwe et al., 2022), as shown in Figure 3. This may not always require new investment but a combination of mobilising new investment and the reallocation of existing capital.

Figure 3. Investment Needs for Climate Action Per Year by 2030

Source: Songwe at al., 2022, p. 23

How will the world mobilise new investment and reallocate existing capital? The capital will need to come from both public and private sources, but much more is needed to unlock and crowd-in private capital in this area.

The challenge is creating the right conditions to grow such investments. In other words, creating a ‘climate-friendly investment climate’.

The solution lies in a combination of institutional capacity and domestic reforms through improved policies and measures (Songwe et al., 2022: 28). Creating a climate-friendly investment climate will need to include policies and measures both on the demand side (encouraging increase in the consumption of low-carbon goods and services) and policies and measures on the supply side (encouraging increase in the production of low-carbon goods and services) (Prest 2022). Policies and measures will also need to address risks associated with scale-up in climate investments, including political, commercial, technological, and currency risks. Policies and measures will also need to promote, attract, facilitate, and incentivise such investments.

The question is what, exactly, policymakers should do.

Two recent analyses attempted to answer this question, including a T20 policy brief in 2022 (Sauvant et al., 2021; Stephenson and Zhan, 2022). The first provided an initial list of potential policies and measures, while the second defined climate FDI[a] and helped build a list of 15 different potential policies and measures.[b]

While this was a commendable start, greater clarity and precision was needed, and the World Economic Forum facilitated a way forward. Across a number of months in 2022 and early 2023, the Forum convened a series of technical meetings with investors, investment authorities, and experts to build on and further refine climate FDI policies and measures.[c] The aim was to produce a ‘Climate FDI Facilitation Guidebook’ that can be used by investment authorities to help grow climate FDI flows.[d] The Guidebook, set to be published in June 2023 in collaboration with Wavteq/fDi Intelligence and made available for free, will provide a ‘how-to’ for four categories of measures identified as particularly important to increasing climate FDI. The four were selected and refined through in-depth consultations (see footnote b), especially considering which measures were most suited to public-private collaboration.

For each of the four priority measures, the Guidebook will lay out: (a) a step-by-step approach; (b) considerations related to implementation and the stakeholders that need to be involved; as well as (c) potential risks and mitigation strategies. The present policy brief aims to capture the primary suggestions to help inform G20 deliberation and action.

2. The G20’s Role

As argued in the 2022 T20 policy brief mentioned earlier, the G20 is the proper forum to support scaling of climate FDI for at least three reasons.

First, climate is one area where G20 economies agree that more action—and especially coordinated action—is needed. The United States (US) and China, for example, notwithstanding their tensions issued in 2021 a number of joint statements and declarations on climate. This indicates that climate action is one area where cooperation is possible even between strategic rivals (State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2021; US Department of State, 2021a and 2021b).

More recently, the US and the European Union (EU) took decisive action to grow climate FDI, whether through the European Green Deal or the US Inflation Reduction Act (2022). The former will encompass €1.8 trillion in investments (European Commission 2023), while the latter includes US$400 billion to help achieve climate goals.

India is also exploring options to attract greater international investment to green sectors, as its remarkable success in expanding green energy has primarily been driven by domestic investments. As of 2020, tracked green finance in India reached US$ 44 billion. Around 83 percent of this was from domestic sources, with the private sector contributing about 59 percent of the domestic investment. However, the annual flows are only one-fourth of the amount needed to achieve the country’s NDCs (CPI, 2022). Thus, it is imperative that international flows must increase rapidly for India to remain on-track to achieve all its NDCs. Within this, FDI will be a priority area for India. Several sectors of the Indian economy are already fairly open to FDI, with minimum regulation; indeed, certain sectors such as renewable energy and electric vehicles have already seen inflows of some form of climate FDI. India will be keen to scale this up, while ensuring that these investments do not come with any conditions that may compromise its ambitious plans to establish a robust manufacturing ecosystem for green industries.

Second, firms carrying out the bulk of FDI are from G20 economies, and therefore helping them grow climate FDI will have a big impact on the world’s climate outcomes (Stephenson and Zhang, 2022, p. 14). Third, once G20 economies adopt policies and measures in support of climate FDI, this will create both a signalling and demonstration effect for non-G20 economies to consider similar approaches.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Recommendation 1. Consider adopting a conceptual framework and definition of ‘climate FDI’ to facilitate coordination and cooperation.

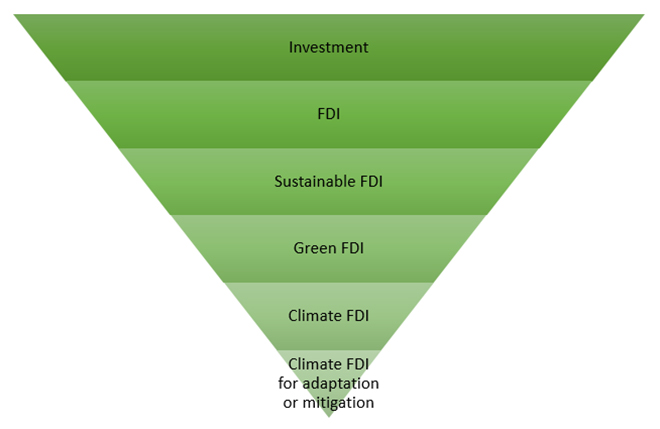

The way to think about climate FDI can be captured in an upside-down triangle that shows the relationship between different types of investment (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Conceptual Framework for Climate FDI

Source: Based on Stephenson and Zhang, 2022: p. 6, updated and revised.

The broadest category includes any investment, whether portfolio investment or direct investment (either foreign or domestic). Then comes foreign direct investment (FDI) as a subset of investment, and then sustainable FDI as a subset of FDI. Sustainable FDI can be defined as FDI that follows principles of responsible business conduct (RBC) and contributes to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals. Continuing down the narrowing conceptual path, green FDI is FDI that aligns with and contributes to the ‘E’ part of ‘ESG’ or the environment. Finally, climate FDI is FDI that aligns with and contributes to the climate dimension of the environment. Within climate FDI, certain projects can contribute to climate adaptation while others, to climate mitigation.

It is worth illustrating the difference between green and climate FDI to avoid confusion. On the one hand, consider an FDI project that ensures that effluents are cleaned before flowing into a river (‘clean river’ example). This would be an example of green FDI, as it does not have a climate impact. On the other hand, consider an FDI project that uses cleaner energy in production that was previously used in that location for that activity (‘clean energy’ case). This would be an example of climate FDI, as it has a climate impact (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Green FDI vs Climate FDI: The Clean River Vs Clean Energy Examples

Recommendation 2. Consider endorsing and using the ‘Climate FDI Facilitation Guidebook’, both within G20 and non-G20 economies through capacity building and technical assistance.

The overall recommendation to the G20 is to consider endorsing and using the Guidebook to grow climate FDI both in their own, and in other economies. G20 policymakers can ensure that their investment authorities consider the Guidebook, especially investment promotion authorities (IPAs). In addition, G20 economies may wish to provide technical assistance and capacity building to authorities in emerging markets and developing countries to consider implementing measures in the Guidebook. This will bring about two interrelated benefits. It will help improve the climate friendliness of investment climates in these economies, and thus help facilitate G20 climate FDI into those economies. At the same time, it will help lower emissions and the carbon content of investment projects around the world, which is needed given the inherently global nature of the climate challenge. Nevertheless, it is important to realise that emerging markets and developing countries may not be in the position to decarbonise as quickly as more developed nations. The solution is to be guided in terms of the depth and direction of climate FDI measures by commitments in each country’s NDCs, as by definition these climate commitments are in line with the priorities and capacities of the country in question.

Finally, different measures will be more relevant to different economies at different points in time. The Guidebook provides four categories of policies and measures to consider, though policymakers may wish to adopt and implement specific measures according to the political and economic conditions in each country.

Measure 1. Align IPA strategies, KPIs, investment incentives and de-risking instruments to NDCs.

The first category of measure is to align IPA strategies, KPIs, investment incentives and de-risking instruments to climate goals identified in NDCs. For instance, ensuring that investment incentives are aligned with—and thus help deliver—NDC goals. Incentives should include not just the fiscal[e] and financial but also those of a non-monetary nature.

Examples of non-monetary incentives can be captured by the heuristic of a ‘red-green-gold’ approach: speed of approvals (red carpet treatment), expedited customs clearances (green channel process), and targeted aftercare (gold status treatment). De-risking instruments such as purchase guarantees (e.g., renewable power purchase agreements) and investment insurance are also important to help crowd-in climate FDI. It is worth noting that insurance many need to address different types of risk, e.g., political risk, commercial, currency risk, and the risk of technology changing and making some technological choices obsolete before the end of the project’s lifetime.

Figure 6. Steps to Roll Out Measure 1

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Measure 2. ‘Match and catch’

The second category of measures is to create a database of domestic suppliers with sustainability dimensions, along with a supplier development program to help domestic firms become more sustainable. This helps ‘match’ investors to domestic suppliers and helps domestic firms ‘catch up’ to the level required by investors.

Having a database of domestic suppliers facilitates investment because it helps overcome information asymmetry between foreign and domestic firms, providing foreign investors with information on domestic suppliers of goods and services they can source domestically. This will lower the time and cost for foreign firms to operate, since they can source inputs domestically that they would otherwise have had to produce themselves or else import.

Supplier databases can be designed to include not only traditional information such as the goods and services offered and contact information, but also information on how domestic firms are operating sustainably. This can help foreign firms select and negotiate contracts with domestic firms that are operating in a climate-friendly manner. It will also encourage domestic firms to increasingly shift to a climate-friendly way of doing business in order to attract and qualify for foreign capital that either aims or requires to be contracting with firms that are operating in such a manner. This has been called a ‘virtuous sustainable investment cycle’ (Stephenson, 2020).

At the same time, supplier development programs can help with the technical assistance and capacity building needed for domestic firms to provide goods and services at the quality, cost, and scale required by foreign firms. Supplier development programs can also be oriented to helping domestic firms acquire the certifications and reach standards of sustainable operations, which can be reflected in the supplier database. When information regarding sustainable operations is included in a supplier database, the database is known as a ‘supplier database with sustainability dimensions’ (SD2). The first SD2 was created by the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC), with the support of the World Economic Forum (CDC, 2023). Other economies may wish to ensure that their supplier databases also include sustainability dimensions.

Figure 7. Steps to Roll Out Measure 2

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Measure 3. Help them help you

The third category of measures is to map the climate commitments of multinational enterprises (MNE) to investment opportunities in host economies and create a pipeline of endorsed and vetted carbon-neutral climate-friendly investment projects that would help MNEs deliver on their commitments. Endorsement by the host government of the pipeline of investment projects de-risks investment in countries that may have relatively more risk or unpredictability.

At the same time, vetting by a third party provides validation and verification that the investment would be designed and implemented in a climate-friendly manner. This creates more certainty for investors to carry out climate investment, as the evidence shows that certainty and predictability are of utmost importance for investment decision-making.

Figure 8. Steps to Roll Out Measure 3

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

How can investment authorities determine MNE climate commitments? Table 1 provides a snapshot of the different platforms where this information may be available. This can help kick-start the search for a good fit between these public commitments and the climate FDI projects that an economy can propose.

Table 1. Potential Sources to Identify MNE Climate Commitments

| Platforms | Description | Strengths & Weaknesses | Examples |

| 1. Company websites & social media | • MNEs may publish their climate commitments, corporate sustainability reports and progress reports on their own websites.• This allows MNEs to showcase sustainability efforts and report on progress made in achieving targets to a wider audience.• Platforms like LinkedIn and Twitter can be used to publish progress reports and engage in conversations with stakeholders. | • Direct engagement with stakeholders and key interest groups.• MNE is accountable to the wider public if climate commitments/pledges are published online.• MNE controls messaging on their websites.• No requirement for commitments to be specific, or mandatory progress reporting to be published on websites. | • Nestlé published commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, using 100% renewables in its operation by 2025[f]• American Airlines published their ESG Report which states their action plan of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2020[g] |

| 2. Sustainability and reporting platforms/ rankings | • Several third-party platforms publish and report on MNE climate commitments to manage their environmental impacts.• In most cases, this information is self-reported and in some cases, independently verified.• Key metrics that are collected and reported on include: GHG emissions, renewable. electricity usage, supply chain emissions, carbon reduction targets and progress made in achieving them. | • Publishing commitments on a recognised third-party platform can increase the credibility of a company’s climate commitments.• Publishing commitments on a third-party platform may garner the MNE greater visibility (beyond their own website/social media).• Several reporting platforms and rankings offer benchmarking services that will allow MNEs to compare their commitments and performance against peers or the industry standard.• Participating in a third-party platform may not always be free (e.g. fee for participation, data collection, consultation). | • SBTi[h]• CDP[i]• Ecovadis[j]• Sustainability Accounting Standards Board[k]• The Climate Pledge (initiative supported by Amazon and Global Optimism) has been joined by more than 300 businesses across 51 industries and 29 countries[l] |

| 3.Industry-specific initiatives | • Some industry have their own sustainability initiatives and platforms for industry players to publish their climate commitments/pledges. | • Allows comparison and comparability of MNE commitments across the industry, and can promote collaboration as companies share best practices in achieving climate commitments.• May promote a one-size-fits-all approach to climate commitments, which may not be meaningful depending on industry composition. | • First Mover Coalition[m] |

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

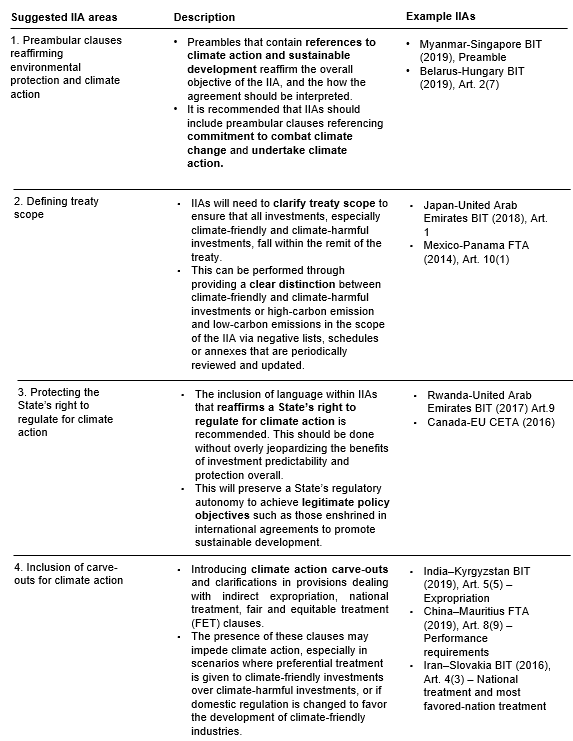

Measure 4. The 5 Cs of climate in IIAs: Clarification, Coordination, Competence, Compel, Carve out

The fourth category of measures is to include climate FDI provisions in international investment agreements (IIAs), with the aim of complementing approaches outlined above with legal instruments.

Under efforts of both UNCTAD (2022a, 2022b) and OECD (2022), a new generation of IIAs is being developed, reforming earlier IIAs and helping develop instruments that accurately reflect society’s climate goals. Concretely, there are a number of ways that climate FDI goals can be integrated in clauses and provisions within a new generation of IIAs (see Table 2).

These can be captured by the five Cs of climate in IIAs:

- Clarification clauses/provisions on how the treaty relates to and covers climate goals

- Coordination provisions that encourage the facilitation of climate FDI between parties

- Competence provisions that convey the state’s right to regulate for climate goals

- Compel provisions that require the parties and their firms to adhere to standards or actions

- Carve out provisions that do not provide the same protection to climate negative investments

Table 2. Ways to Include Climate FDI Provisions in IIAs and Examples

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming), based on UNCTAD (2022a and 2022b) and OECD (2022)

When reviewing and reforming IIAs or developing new IIAs, it is important to ensure that the text aligns with sustainable objectives and climate objectives, while also promoting, facilitating and protecting investments. One suggested aspect to consider is the inclusion of clauses that encourage and facilitate climate FDI (or sustainable investment more broadly), as prima facie this would only have upsides and no downsides, in that such provisions are likely to only help support and promote climate FDI flows. This approach is captured above by the second ‘C’, ‘2. Coordination’.

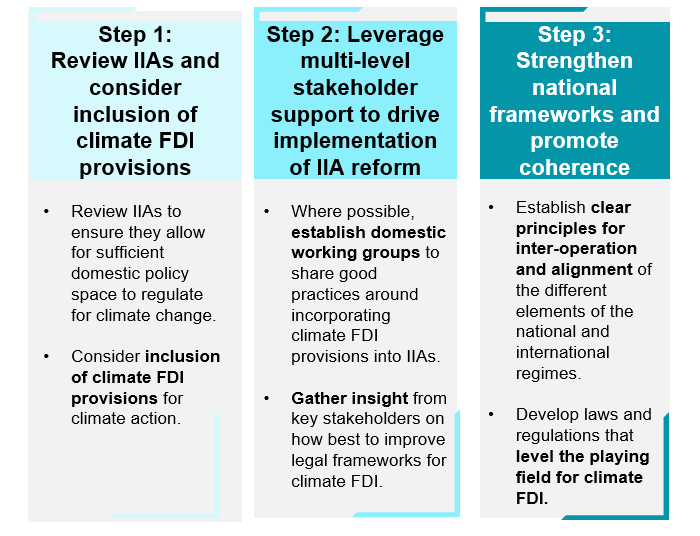

It is worth acknowledging that approaching climate FDI from the legal side will take longer than any of the earlier measures that are easier to facilitate. However, notwithstanding the greater time and effort this may take, over time, climate FDI provisions in legal instruments are likely to have a significant impact on growing these investments. Figure 9 suggests how investment authorities may approach this process.

Figure 9. Steps to Roll Out Measure 4

Source: World Economic Forum and Wavteq/fDi Intelligence (forthcoming)

Recommendation 3. Consider creating a Coalition of IPAs for Climate.

One way to help operationalise climate FDI measures and scale collaboration on growing such investment is through a potential Coalition of IPAs for Climate.[n] This idea is currently under discussion, with the aim of potentially launching such a coalition in Davos in January 2024. The World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (WAIPA), which supports the initiative, will play in important role.

What would the coalition do in practical terms? As a first step, coalition members would first endorse at the CEO level a statement—circulated and discussed in Davos in January 2023 (see Annex)— on the importance of increasing climate FDI and the opportunity to use climate FDI measures to do so. As a second step, coalition members would aim to use the Guidebook to implement climate FDI measures.

While there have been a number of other coalition mechanisms to mobilise action in support of climate goals, this would be the first time that IPAs specifically add their voice and muscle to the effort. To illustrate, the First Movers Coalition brings together 65 companies and at least 10 government partners so far, that have committed to support carbon goals through procurement decisions (US Department of State, 2022). Meanwhile, the Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate brings together ministers from 50 countries that have agreed to leverage trade for climate goals (EC, 2023). Adding the investment piece to this puzzle could help all parties better achieve climate goals, given that investment and trade are two sides of the same coin, and that procurement can be considered a form of investment.

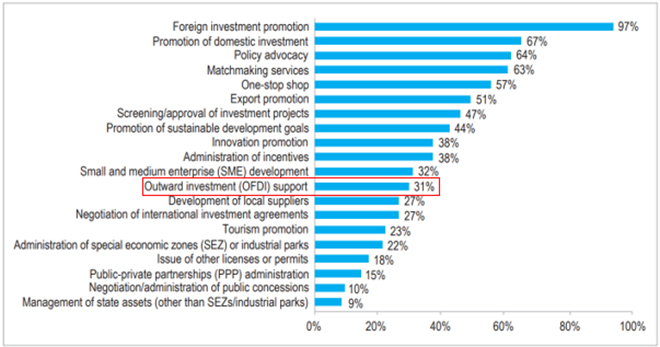

In addition, FDI flows are increasingly two-way, with IPAs facilitating not only inward FDI, but also outward FDI (see Figure 10, red box). This is due to the realisation that outward FDI can lead to increased growth and competitiveness of firms and home economies, acting as complementary channel to inward FDI for development (Stephenson and Perea, 2018). As a result, there is scope for two-way, mutually beneficial climate FDI facilitation between IPAs of G20 economies, as one economy’s inward FDI is by definition another economy’s outward FDI (Stephenson, 2018).

Figure 10. Incidents of Mandates of IPAs (2019, n = 91).

Source: Sanchiz Vicente and Omic (2020)

4. Conclusion

The world needs more investment to help achieve and deliver its climate goals—but where to start? This policy brief outlined four concrete, practical measures that G20 policymakers may wish to consider, providing step-by-step suggestions for how to do so. These measures are captured—and further developed—in a Guidebook on Climate FDI Facilitation, which provides more detail on each, and can serve as a complementary resource. A Coalition of IPAs for Climate could also help catalyse and scale cooperation in this space, providing mutually gainful outcomes for G20 economies, and the world.

Attribution: Matthew Stephenson and Samir Saran, “Creating a Climate-Friendly Investment Climate,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Annex

References

de Coninck, H., A. Revi, M. Babiker, P. Bertoldi, M. Buckeridge, A. Cartwright, W. Dong, J. Ford, S. Fuss, J.-C. Hourcade, D. Ley, R. Mechler, P. Newman, A. Revokatova, S. Schultz, L. Steg, and T. Sugiyama, 2018: Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte,V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M.Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 313-444.

Climate Policy Initiative, Landscape of Green Finance in India, 2022.

Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC), The Suppliers Database with Sustainability Dimensions (SD2), (retrieved 8 April 2023)

European Commission (ECa), “A European Green Deal Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent”, Accessed 8 April 2023.

ECb, Trade and Climate: EU and partner countries launch the ‘Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate, Press Release, 19 January 2023.

International Finance Corporation (IFC), “Climate Investment Opportunities in South Asia: India”, n.d.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Survey of climate policies for investment treaties”, 11 October 2022.

Prest, Brian C. 2022, Partners, Not Rivals: The Power of Parallel Supply-Side and Demand-Side Climate Policy, Resources for the Future, Report 22-06, April 2022.

Rogelj, J., D. Shindell, K. Jiang, S. Fifita, P. Forster, V. Ginzburg, C. Handa, H. Kheshgi, S. Kobayashi, E. Kriegler, L. Mundaca, R. Séférian, and M.V.Vilariño, 2018: Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 93-174.

Sanchiz Vicente, Alex and Omic, Ahmed. State of Investment Promotion Agencies: Evidence from WAIPA-WBG’s Joint Global Survey (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2020.

Sauvant, Karl P. and Stephenson, Matthew and Kagan, Yardenne, Green FDI: Encouraging Carbon-Neutral Investment (October 18, 2021). Columbia FDI Perspectives, No. 316, 2021, SSRN.

Songwe V, Stern N, Bhattacharya A. Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2022.

Stephenson, Matthew. “Investment as a two-way street: how China used inward and outward investment policy for structural transformation, and how this paradigm can be useful for other emerging economies”, PhD Dissertation, Graduate Institute for International and Development Studies, 2018.

Stephenson, Matthew. 5 ways the WTO can make investment easier and boost sustainable development. World Economic Forum Agenda Article, 10 November 2020.

Stephenson, Matthew and Jose Ramon Perea. “Outward foreign direct investment: A new channel for development”, World Bank, Private Sector Development Blog, 23 October 2018.

Stephenson, Matthew and Zhan, James X. What is Climate FDI? How can we help grow it? T20 Policy Brief, 2022.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China, US issue joint declaration on enhancing climate action”, 11 November 2021, Xinhua.

US Department of State, “U.S.-China Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis”, Media Note, 17 April 2021, 2021a.

US Department of State, “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s”, Media Note, 10 November 2021, 2021b.

US Department of State, “First Movers Coalition Announces Expansion”, Media Note, 9 November 2022.

[a] “Climate FDI can be determined on the basis of investment impact, rather than the traditional methodology of defining FDI based on investor motivation (Dunning, 1982). In other words, climate FDI is any investment that leads to measurable improvement in climate conditions in a host economy, regardless of sector or activity” (Stephenson and Zhang, 2022: 6).

[b] Related work by Joachim Monkelbaan and Jose Vieira Martins had identified a longer universe of 38 different policies and measures, which was synthesised and prioritised through an internal working group at the World Economic Forum.

[c] Virtual and in-person meetings of the community to discuss climate FDI policies and measures took place on 21 July 2022, 9 November 2022 at COP27, 14 December 2022, 18 January 2023 at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, and on 29 March 2023.

[d] To help produce the Guidebook, specialized consulting firm WAVTEQ was selected as a partner, and has helped build out information on the top climate FDI measures through additional interviews and research. WAVTEQ has since been acquired by The Financial Times.

[e] Fiscal incentives to attract FDI will lose some of their effectiveness following the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process. If host states levy less than the 15 percent minimum tax on firm profits, other specified jurisdictions can charge a ‘top-up’ tax and pocket this amount, incentivising host states to meet the 15 percent threshold or lose fiscal revenue without gaining investment attractiveness. Please see Stephenson and Zhan, “We’ve entered a new era for investment policy and promotion”, forthcoming. The authors also wish to acknowledge Karl Sauvant for raising this point during the 29 March 2023 consultation.

[f] Climate action | Nestlé Global (nestle.com)

[g] American Airlines ESG – American Airlines (aa.com)

[h] How it works – Science Based Targets

[l] The Climate Pledge | Be the planet’s turning point

[m] About > First Movers Coalition | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

[n] This idea was first proposed by Soumyajit (‘Jeet’) Kar, Specialist, Sustainable Trade and Resource Circularity, World Economic Forum.

SOURCE – T20 ORF Policy Brief.

Interview – “[Brazil and India] have a stake and voice, by rights, not indulgence”

Over the past decades, India has witnessed unprecedented growth not only in economic terms but also in terms of its international prominence. Has India effectively utilized its participation in the G20 to showcase global leadership potential emerging from developing nations?

Samir Saran: By all counts, the Indian Presidency of the G20 can be assessed as having been an outstanding success. The Indian leadership was able to ensure that the dynamic federal architecture was able to jointly deliver on the objectives that had been spelled out at the outset. Every state of India was involved, in some cases infrastructure was invested into certain parts of the country, and in all instances visible support of people and polity was in evidence. The G20 became a people’s project and India hosted about 220 meetings in 60 cities.

From a global perspective, India determinedly and delicately ensured that the Global South became a participant, and it could contribute to the agenda for the grouping this year.

From a global perspective, India determinedly and delicately ensured that the Global South became a participant, and it could contribute to the agenda for the grouping this year. India walked an extra mile to understand their concerns and expectations, and also ensured that some were also invited to the proceedings. It conducted two Voices of the Global South conferences under the chairship of the Indian Prime Minister indicating the seriousness with which it took this task. This has lent legitimacy to its international standing within this very large group.

Finally, at a time of polarized politics and breakdown of trust among countries, India fashioned an ambitious declaration in Delhi that responded to issues that are important to all. It achieved consensus amongst countries on matters that had been left unresolved in other multilateral forums. Its ability to deliver this outcome demonstrated its leadership and that of the emerging and developing countries to contribute significantly and effectively to matters pertaining to global governance. Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, in the consecutive years of Presidency have an opportunity to showcase the importance and prominence of emerging country leadership in world affairs.

India and Brazil find themselves in a unique position, jointly leading a troika of developing countries. Drawing on India’s experience, can it wield the potential to reshape G20 outcomes? Could you provide concrete examples of results aligning with the Global South perspective?

SS: Brazil has an even bigger opportunity than India did. India’s troika with Indonesia and Brazil straddles two continents–Asia and Latin America. Brazil has the advantage of having a troika which includes South Africa and, therefore, the African continent. It is an opportunity which must be capitalized to articulate our common challenges as leaders in the developing world. Brazil has declared poverty reduction as a key theme of its G20 Presidency and this is very relevant. It is an indication of both our challenges and our aspirations. Equality and Equity, even as we grow and develop, are another Brazilian objective and resonate with developing societies.

Brazil has an even bigger opportunity than India did. India’s troika with Indonesia and Brazil straddles two continents–Asia and Latin America. Brazil has the advantage of having a troika which includes South Africa and, therefore, the African continent.

India had strived hard with its partners to have a result-oriented G20. India had 87 outcome documents and 118 action items coming out of its Presidency. The African Union’s addition to the G20 is of course a key achievement. The adoption of a framework on Digital Public Infrastructure is also a significant milestone. Both of these are at the core of the Global South expectations.

The Indian Presidency has also gone further on the social protection agenda. It has come out with G20 Policy Priorities on Adequate and Sustainable Social Protection and Decent Work for Gig and Platform Workers & G20 Policy Options for Sustainable Financing of Social Protection. This is an important part of the Brazilian agenda as well and corresponds with what is needed in developing countries.

Despite the undeniable significance of the G20, the group faces criticism for inherent characteristics like the absence of a permanent Secretariat, insufficient means for implementation monitoring, and perceived lack of representation due to its “elite” membership. Drawing from your first-hand experience, do these criticisms hold merit? What are the primary challenges and gains associated with a grouping like the G20?

SS: We should look at each of these criticisms discretely. First, on the lack of a permanent Secretariat, one may ask if this is in fact a criticism. The G20 has functioned without overzealous bureaucracies. It may well be one of the secrets to its continued functioning. What we may need is a central repository of G20 knowledge rather than a Secretariat.

The knowledge repository brings us to the second criticism of implementation and monitoring. Leveraging the knowledge repository may allow us to hold the G20 members accountable for their commitments.

The lack of representation is a weakness of any plurilateral grouping. The ideas which brought the group together are the criterion for its exclusivity. It so happens that the G20 members are economically elite because they currently contribute the most to global GDP. The membership should adapt and change with the times. We have started this process with the addition of the African Union to the group. And the efforts of India to partner with the Global South in many ways smashed the glass ceiling and made the G20 relevant and respond to the leadership of the Global South.

At the think tank / academic level, we at ORF (Secretariat of the Think 20) were able to solicit policy briefs from over a 1,000 authors from over 75 countries and ensured that the process is inclusive and open to all. Some of our important convenings outside of India were in Kigali, Rwanda, and Cape Town, South Africa. These established the inclusive design of the Indian Presidency.

As a leader within one of the G20 engagement groups, the Think20, you have had the opportunity to observe how the integration of civil society on official negotiation tracks functions. Does civil society play a substantial role in agenda-setting or decision-making within the official G20 agenda? If so, how can these opportunities be expanded?

SS: We cannot speak on past Presidencies but can say with confidence this year that civil society has contributed to the official G20 agenda. The energy with which the G20 India team followed and engaged with conversations in all the engagement groups is a reflection of these. We have also seen some of our ideas find space in the Leader’s Declaration.

The addition of the African Union, the commitment to expand climate finance, and the push for digital public infrastructure were all at various points recommended by Think20 India.

The concept of Task Force notes introduced by T20 Indonesia was elevated to Task Force statements by T20 India. It was something that ensured more engagement with the specific Sherpa tracks. For instance, the Trade and Investment Working Group may not want to wait for the full Think20 Communique which may have specific recommendations. It may have more interest in the full statement of the Task Force on Macroeconomics and Trade.

Innovations such as this help academia and think tanks make more valuable and timely contributions to the G20 process.

India and Brazil have a history of coordinating positions in various multilateral forums such as the United Nations, BRICS, IBSA Dialogue Forum, and the World Trade Organization G20. Can the G20 be considered a noteworthy example of the potential for Indian-Brazilian cooperation?

SS: Brazil-India have been reliable partners to each other. At the G20, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organization, the partnership takes on a unique global character. At BRICS, IBSA, and other smaller groups, the partnership is characterized by a conversation amongst similarly situated and aligned countries barring a few exceptions.

Brazil and India have a vital role in keeping the focus on development in these international plurilateral groups. We have a stake and voice, by rights, not indulgence. The two countries are both aware of this and leverage their voice accordingly. The role of the troika in the success of a G20 Presidency is an open secret.

Brazil and India have a vital role in keeping the focus on development in these international plurilateral groups. We have a stake and voice, by rights, not indulgence. The two countries are both aware of this and leverage their voice accordingly. The role of the troika in the success of a G20 Presidency is an open secret. Our collaboration at the international level on behalf of the Global South is something we should maintain momentum on and continue to permanently center development as the most important mission of the G20. This would certainly be a triumph of the Indian-Brazilian partnership in world affairs.

In India, the Banker’s G20 became the People’s G20. Brazil, with its rich constituency of civil society and research organizations, will take this forward and shape the process indelibly.

This interview was given to CEBRI-Journal in November 2023.

The Only Way to Make Climate Progress

Green technology and capital is concentrated in rich countries. Here’s how to address the north-south divide.

The recent United Nations climate summit, known as COP28, offered a glimmer of hope for international climate action. Negotiators struck a deal to transition the world away from fossil fuels and formally approved a loss and damage fund to support the countries that are most vulnerable to climate impacts. Yet COP28 fell short in one major area: It did not outline a clear pathway for funding and implementing climate action in the global south.

The implications of this will be felt around the world. Despite landmark U.N. climate agreements, global emissions have continued to rise. New research suggests that the world will breach the critical threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming above preindustrial levels by the end of the decade.

As emissions peak in the developed world, future emissions growth will be concentrated in the global south. Yet the resources needed to limit these emissions—namely, green technology and capital—are concentrated in the global north.

The global energy transition will only be successful if the international community fixes the north-south divide. Critical capital must no longer be withheld from the parts of the world that require it the most. There is an urgent need for leaders to reimagine climate cooperation. They can do this by ensuring that the global south has access to the financing, technology, and forums it needs to scale up energy access, support communities most affected by climate change, and make progress on climate targets.

The global energy transition will only be successful if the international community fixes the north-south divide. Critical capital must no longer be withheld from the parts of the world that require it the most.

Countries in the global south have felt cheated by international climate conferences that often overlook their voices and needs. These nations are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of a warming planet; in 2023, climate-induced natural hazards were among the foremost threats to lives and livelihoods in places including Libya, Yemen, Pakistan, and East Africa.

Yet countries in the global north have not only refused to make binding commitments to reduce emissions, but have also failed to deliver on the meager promises they have made, such as a 2009 commitment to provide $100 billion annually to the global south by 2020.

The resulting tussles between both sides distract from the real scale of the problem. It is not enough to think in terms of billions. The final text at the 2022 U.N. climate summit noted that the world would need to invest between $4 and $6 trillion annually in renewables and decarbonization solutions to transition to a low-carbon economy. Even less ambitious targets call for between $2 and $3 trillion in annual investments. Yet instead of identifying solutions to raise this kind of money, negotiators have fought over small, insignificant change.

Most of these investments will need to go to the global south. Currently, only around 25 percent of global climate finance, both private and public, flows to the global south. Yet in the next three decades, most global energy demand growth will come from these countries as they seek to address severe energy poverty. The International Energy Agency has estimated that one-quarter of this growth between 2019 and 2040 could come from India alone.

Since much of the global south’s energy infrastructure has not been built, there is an opportunity for development that does not follow the carbon-intensive pathways of the global north.

Most of these investments will need to go to the global south. Currently, only around 25 percent of global climate finance, both private and public, flows to the global south.

The good news is that green technologies have become increasingly cost-effective; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has estimated that the average cost of solar and wind energy and batteries has dropped by up to 85 percent since 2010. But the private sector only tends to see a clear business case for green investment in the global north, where more than 80 percent of total global climate finance is concentrated. In the global south, by contrast, only 14 percent of green investment comes from the private sector.

That’s because climate investment often requires considerable upfront capital and can take years to yield substantial returns. That initial investment has proved a hurdle for the global south to securing private funding. The International Energy Agency has estimated that the nominal financing costs for green energy can be seven times higher in developing and emerging economies compared with the United States and Europe.

This imbalance in capital costs is partly due to sovereign risk, or the political risks of investing in developing countries. Yet, while sovereign risk is real, it is often exaggerated and should not outweigh climate risk, which poses the greatest threat to the stability of the international financial system.

The technology needed to scale up green energy solutions also remains concentrated in the developed world and China. The global south often has to pay a heavy premium to use these technologies, including solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage technologies.

Global leaders will need to resolve these disparities to meet their climate targets. Fortunately, climate action already aligns with much of the global south’s national development strategies. As the rotating president of the G-20 last year, India highlighted the need to place green development at the heart of climate action. But the global south can’t do it alone.

The global south often has to pay a heavy premium to use these technologies, including solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage technologies.

There are four critical steps that the international community can take to rebuild trust in the climate action process and advance global cooperation.

First, the international financial system needs urgent reform to encourage more private funding in the global south. This will be essential to renewable energy projects and other mitigation measures. But it will also support adaptation efforts, including regenerative agriculture, drought-resistant practices, and low-cost community infrastructure such as bunds to protect against sea level rise and salination.

Multilateral and bilateral development institutions should expand financial guarantees and blended finance mechanisms to reduce the perceived risks associated with investments in the global south. For example, G-20 countries could create a pool of capital—administered by an agency such as the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, which is housed in the World Bank—with the sole aim of reducing the cost of capital for climate-related projects.

Multilateral development banks must also be reformed to tackle the climate crisis. These banks can be instrumental in taking on some of the risks that hinder private capital flows to the global south. An independent committee under India’s G-20 presidency put forward a road map to reform such banks so that they prioritize eliminating extreme poverty; tripling sustainable lending levels; and creating a new, flexible funding mechanism. The G-20, as well as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, should build on this road map by establishing hard timelines for implementing the reforms and ensuring support for green projects.

Second, the international community must ensure that the global south has access to technology it needs for the energy transition. In the health sector, there is a global understanding that while intellectual property protection is vital for innovation, governments may have to override protections in emergencies; in those rare instances, governments can turn to compulsory licenses to use a patent without the consent of the patent holder. Despite this precedent, the COVID-19 pandemic showed the world that even lifesaving technology may not flow quickly enough to the global south in a health emergency.

Before climate emergencies worsen, regulators and global institutions need to identify clearer mechanisms to share intellectual property rights for critical technologies and disseminate climate tech. This will be essential to ensuring that the green transition is not afflicted by severe delays and global disputes similar to those witnessed during the pandemic.

Emerging economies are also starting to see homegrown clean tech ecosystems driven by start-ups looking to disrupt traditional energy systems. Yet this sector suffers from a lack of public funds, reduced access to cutting-edge tech, and a shortage of early-stage risk capital to reach commercial scale. New mechanisms to connect risk capital in the global north to the clean tech sector in the global south will be essential to bridging the technology gap—for instance, a $100 billion fund that would disburse money to around 120 companies in the global south, including start-ups that plan to scale up climate tech.

Emerging economies are also starting to see homegrown clean tech ecosystems driven by start-ups looking to disrupt traditional energy systems.

Third, multilateral forums, such as the UNFCCC and the G-20, should better acknowledge the role of women in climate action, especially in the global south, and create women-led initiatives to mobilize support for political action on climate. Women are especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change—in many countries, they bear the responsibility of securing resources such as food and water that are made scarcer by global warming. Investing in female leadership will help shift the climate conversation from an elite discussion to one grounded in the real concerns of households.

Women are also the most likely to face health impacts from climate-related hazards, and public health systems worldwide will have to adapt to new climate-related risks. Putting health and gender equality at the center of the global climate conversation will create new reasons for climate action.

Finally, the world needs to build new pathways for climate cooperation. Despite geopolitical divides, nearly every country has a national action plan for climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate action has driven greater regional dialogue, including through the African Union’s Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan and Central Asia’s Bishkek High-Level Dialogue on Climate Change and Resilience.

Climate action has also led to inadvertent cooperation among great powers, such as the United States and China. This kind of cooperation, which is often driven by the private sector, has been a key enabler of supply chains essential for green energy growth.

Countries with similar capabilities and concerns should collaborate in smaller groupings for faster and more ambitious action.

Climate cooperation can—and should—become a way to restore global stability and trust in multilateralism. Leaders should energize inadvertent cooperation through new partnerships, institutions, and dialogues. Countries with similar capabilities and concerns should collaborate in smaller groupings for faster and more ambitious action. The “climate club” that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz launched at COP28 to support decarbonization among some 36 member states is a good start. But the world needs an alliance with equal representation from partners in both the global north and south that can implement a binding finance package to channel transformative climate finance to the global south.

The international community must reimagine the global climate governance framework to address the scope of today’s climate challenge. As the clock ticks down to prevent catastrophic warming, only innovative approaches can mitigate damage to our planet. Key to this will be ensuring that the most vulnerable countries are no longer shut out of the capital and technology that they need to transition to green, resilient economies.

This commentary originally appeared in Foreign Policy.

Technology: Taming – and unleashing – technology together

Innovative approaches will require regulatory processes to include all stakeholders.

Technology has long shaped the contours of geopolitical relations – parties competed to outinnovate their opponents in order to build more competitive economies, societies and militaries. Today is different. With breakthroughs in frontier technologies manifesting at rapid rates, the question is not who will capture their benefits first but how parties can work together to promote their beneficial use and limit their risks.

The challenge: benefits of frontier technologies may be compromised by inequities and risks

The prolific pace of advancement of frontier technologies – artificial intelligence (AI), quantum science, blockchain, 3D printing, gene editing and nanotechnology, to name a few – and its pursuit by a multitude of state and non-state actors, with varied motivations, has opened a new chapter in contemporary geopolitics. For state actors, these technologies offer a chance to gain strategic and competitive advantage, while for malicious nonstate actors, these technologies present another avenue to persist with their destabilizing activities.

Therefore, emerging technologies have added another layer to a fragmented and contested global political landscape. Besides shaping geopolitical dynamics, they are also transforming commonly held notions of power – by going beyond the traditional parameters of military and economic heft to focus on states’ ability to control data and information or attain a tech breakthrough as the primary determinant of a state’s geopolitical influence.

These technologies also have significant socioeconomic implications. By some estimates, generative AI could add the equivalent of $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion to the global economy and boost labour productivity by 0.6% annually through 2040.14 Yet, simultaneously, the rapid deployment of these technologies has sparked concerns about job displacement and social disruption. These dynamics are triggering new geopolitical alignments as states seek to cooperate or compete in developing and using new technologies.

As frontier technologies take centre stage in global politics, they present a new challenge for international diplomacy.

As frontier technologies take centre stage in global politics, they present a new challenge for international diplomacy. What can states do to stem the proliferation of frontier dual-use technologies in the hands of malicious actors who intend to cause harm? Can states look beyond their rivalries to conceive out-of-the-box solutions, or will they always be playing a catch-up game with tech advancements? What role behoves the United Nations-led multilateral frameworks regarding the global governance of these technologies, or will plurilateralism and club-lateralism trump it?

A new approach for governing frontier technologies

The historical evolution of global tech regimes offers important lessons for the challenges posed by frontier technologies today. During the Cold War, industrialized nations established export control regimes, such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the Missile Technology Control Regime, that sought to exclude certain countries by denying them several dual-use technologies. Those control regimes proved successful in curbing tech proliferation. However, with changing geopolitical realities, the same regimes began extending membership to previously excluded countries. This approach offers a vital lesson: shedding the initial exclusivist approach in favour of extending membership helped to retain the regimes’ legitimacy.

Secondly, while the multilateral export control regimes succeeded, the nuclear non-proliferation regimes performed sub-optimally as they amplified the gap between nuclear haves and have-nots. This triggered resentment from the nuclear have-nots, who sought to chip away at the legitimacy of the regimes.

The key lesson for today is that the success of any tech-related proliferation control efforts is contingent on not accentuating existing technology divisions between the Global North and South.

The UN-led multilateral framework has focused on enhancing global tech cooperation through initiatives like the Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation. However, while there has been little substantive progress at the global, multilateral level, bilateral and minilateral tech cooperation has thrived. Groupings such as the Quad, AUKUS and I2U2 that focus on niche tech cooperation present a possible model pathway forward.15 They have demonstrated the value of like-minded partners coming together to realise a common vision and ambition. These arrangements also suggest that even as the UN-led multilateral frameworks attempt to grapple with frontier technologies, minilaterals may provide the starting point for collaboration to address frontier technologies’ advancement.

To ensure that efforts at tech regulation succeed, countries will be required to undertake innovation in policy-making, where governments take on board all the stakeholders – tech corporations, civil society, academia and the research community. The challenge posed in recent months by generative AI through tools like deep fakes and natural language processing models like ChatGPT has shown that unless these stakeholders are

integrated into policy design, regulations will always be afterthoughts.

How to strengthen tech cooperation

The following are four proposals for strengthening global cooperation on frontier technologies:

– Develop the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) framework for emerging technologies: Similar to the R2P framework developed by the UN for protecting civilians from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, the international community must create a regulatory R2P obligation for states to protect civilians from the harms of emerging technologies. This obligation would entail three pillars: 1) the responsibility of each state to protect its populations from the emerging technologies’ misuse, 2) the responsibility of the international community to assist states in protecting their populations from the emerging technologies’ misuse, and 3) the responsibility of the international community to take collective action to protect populations when a state is manifestly failing to protect its own people from the emerging technologies’ misuse. The specific measures that are needed will vary depending on the specific technologies involved and the risks that they pose.

– Design a three-tier “innovation to market” roadmap: States must ensure responsible commercial application and dispersion of new technologies. One critical step towards this is for states to design a three-tiered tech absorption framework comprising a regulatory sandbox (pilot tested in a controlled regulatory environment for assessing collateral impact), city-scale testing and commercial application.

– Convene a standing Conference of the Parties for future tech: The Global South must convene a standing Conference of the Parties (COP) for future technologies along the lines of COP for climate change negotiations. This body would meet on an annual basis where the multistakeholder community – national governments, international organizations and tech community – will deliberate on new tech developments, present new innovations and reflect on related aspects of the dynamic tech ecosystem and its engagement with the society and communities.

– Link domestic innovation ecosystems: Inter-connected national innovation ecosystems will ensure that like-minded countries can pool their finite financial, scientific and technological human resources to develop technologies. For instance, in the field of quantum science, the European Commission’s research initiative, the Quantum Flagship, has partnered with the United States, Canada and Japan through the InCoQFlag project. Likewise, the Quad has the Quad Center of Excellence in Quantum Information Sciences. This underlines the importance of prioritizing one of the frontier technologies and networking domestic innovation ecosystems to focus on its development, as no country alone can harness the deep potential of frontier technologies and mitigate the associated risks.

Technology as a tool of trust

Throughout history, technology has been the currency of geopolitics. New innovations have bolstered economies and armies, strengthening power and influence. Yet, technology has also served as an opportunity to bind parties closer together. Today, at a time of heightened geopolitical risks, it is incumbent on leaders to pursue frameworks and ecosystems that foster trust and cooperation rather than division.

This essay is a part of the report Shaping Cooperation in a Fragmenting World.

4 pathways to cooperation amid geopolitical fragmentation

The world is experiencing geopolitical turbulence. Wars are raging across the Middle East, Europe and Africa; 2023 marked the largest ever single-year increase in forcibly displaced people.

In addition to these security challenges, the world faces a warming planet and fragile global economy that can only be addressed through joint action.

Despite this daunting picture, there are ways the international community can still work together. Experts from the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Geopolitics tell us how, in a new report entitled Shaping Cooperation in a Fragmenting World.

The report offers innovative pathways towards greater global cooperation in four areas: global security, climate action, emerging technology and international trade.

Below are the key highlights, as outlined by our experts.

1. Global Security – advancing global security in an age of distrust

By Bruce Jones, Ravi Agrawal, Antonio de Aguiar Patriota, Karin von Hippel, Lynn Kuok and Susana Malcorra

The starting point must be to recognize that distrust is, in the short and medium term at least, a baked-in feature of geopolitical reality.

Managing this and forging responses to global challenges despite it requires recognizing that collaboration is possible even under conditions of intense distrust: the US and the Soviet Union repeatedly proved this during the Cold War.

Third parties are key to managing the distrust through quiet diplomacy (often at or through the UN), brokering offramps, de-escalation and crisis avoidance. So-called “middle powers” have in the past played a key role in great power conflict prevention and de-escalation and are an important part of this moving forwards.

Although this term has, until recently, been confined to Western countries, shifts in the global balance of power mean that it extends beyond the West to “rising” powers elsewhere.

A standing mechanism that links the western major and middle powers with the non-Western ones (Brazil, India, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates and so on) would create a diplomatic mechanism that could straddle the increasingly bifurcated worlds of the G7, Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad) and the expanded BRICs.

2. Climate Change – rethinking climate governance

By Samir Saran and Danny Quah

There is now a need to rethink global climate governance. The fundamental imbalance is this that while the developed world has been the key contributor to historical emissions, future emissions will be concentrated in the developing world. It is necessary to not just increase the amount of private capital deployed in the Global South, but also to ensure the scope of such investment is widened to include adaptation.

Similarly, the technology needed to scale up green energy solutions also remains concentrated in the developed world and China. The mandate and lending patterns of multilateral development banks should be changed and the start-up sector in the emerging world should be repositioned towards climate goals.

At the same time, multilateral forums such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the G20 must better acknowledge and differentiate impacts of climate change on health outcomes across genders and craft women-led initiatives to mobilize societal support for political action.

3. Emerging Technology – taming technology together

By Samir Saran, Flavia Alves and Vera Songwe

The prolific pace of advancement of frontier technologies and its pursuit by a multitude of state and non-state actors, with varied motivations, has opened a new chapter in contemporary geopolitics.

To ensure that efforts at tech regulation and stemming their proliferation succeed, countries will be required to undertake innovation in policy-making, where governments take on board all the stakeholders – tech corporations, civil society, academia and the research community.

Similar to the responsibility to protect (R2P) principle developed by the UN for protecting civilians from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, the international community must create a regulatory R2P obligation for states to protect civilians from the harms of emerging technologies.

And the Global South must convene a standing conference of the parties (COP) for future technologies, along the lines of COP for climate change negotiations.

4. International Trade – expanding and rebalancing trade

By Nicolai Ruge and Danny Quah

Strengthening and rebalancing the trade system requires expanding the trade agenda, not limiting it. The broader the benefits delivered by trade, the more firmly it will be aligned with national and global priorities.

Trade that is designed to deliver on globally shared priorities as defined by the UN Sustainable Development Goals will gain the trust of governments and citizens and be “fenced off” from geopolitical rivalry rather than disrupted for near-term political wins.

To rebuild global trust in the benefits of the multilateral trade system, it is of paramount importance that the Global South – and particularly least-developed countries – are not cut out of the growth and development pathways that participation in international trade provides.

Mechanisms must be in place to ensure they are able to take advantage of new opportunities created by shifts in global value chains.

How can these pathways be successful?

Throughout the report , one common factor emerged as key to enhancing cooperation across these four domains: inclusivity.

To address challenges in global security, climate change, emerging technology and trade, the international community must prioritize diverse voices and involve actors that have previously been on the margins of multilateral fora.

With this approach as a North Star, building cooperation is possible.

This publication originally appeared in World Economic Forum.